CONTENTS 1. Introduction to Miners' Halls 2. Ammanford Miners' Hall 3. The Committee Man 4 Epilogue 5. Sources

1. INTRODUCTION TO MINERS' HALLSOne of the defining sights of industrial Wales was the workmen's hall, often sharing the skyline with those other icons of the valleys, the pit-head gear of the collieries, and the somewhat forbidding architecture of the chapels. Unlike the collieries, which were the fruit of the coal owners' imaginations (though this fruit could not have been harvested without the labours of their workforce), the miners' halls were built and run by the men who laboured underground to extract the coal for others' profit. Only the chapels now remain: every colliery has been closed, their pit-head gear dismantled, the shafts sealed up, and the spoil tips landscaped or removed. Many, though not all, of the miners' halls have also vanished and if most of the 5,000 Welsh non-conformist chapels still stand, many of them stand empty, and their futures can no longer be taken for granted. This inter-dependence of mine, chapel and workmen's hall is now unravelling, and unravelling fast.

They go by various names—Miners' Hall, Welfare Hall, Workingmen's Hall, or Public Hall—and many of them have the word 'Institute' appended to signal that they had an educational purpose for their existence. But whatever their name, they all had one thing in common—they represented the hopes and aspirations of men who went to work in the mines and factories as young as 12 with little or no education behind them, and even less chance of improving their lot in life. Almost all of the halls trace their origins to the 1920s and 1930s and they were all funded by the 'check-off' system, whereby weekly contributions were deducted from the workers' wages, initially to build the halls, and subsequently to run them.

The Amman valley once had five workmen's halls along its mere eight-mile length, plus a sixth in nearby Llandybie, probably the highest density of halls in Britan. A journey down the valley once took you past halls at Cwmllynfell (opened 1934), Brynamman (1926), Gwaun Cae Gurwen (1932), Garnant (1927), Ammanford (1932) and Llandybie (1925), all built in just nine years. Only three of these halls still survive in the valley today. Brynamman Workmen's Hall is still thriving as a cinema and run on a voluntary basis by a local committee. Ammanford Miners' Welfare Hall has been revived and renovated in recent years after a lengthy spell with its doors closed and windows boarded up. Llandybie Public Memorial Hall continued as a community centre after its cinema closed in 1960, its fortunes reviving with a major renovation in 2007. All these halls had originally been built with the aid of the 1920 Miners' Welfare Fund, while the Lottery Fund has been the saviour this time around, the Miners' Welfare Fund having ceased to exist due to the remorseless post-war pit closure programme.

The major impetus for the building of these Welfare Halls was the creation of the Miners' Welfare Fund, to be administered by the Miners' Welfare Commission under the Mining Industry Act of 1920. This Act authorised the collection of a levy from the coalowners of one penny for each ton of coal produced—the 'magic penny'—to provide amenities for the mineworkers and their families. As well as the Workmen's Halls, pithead baths, educational facilities and scholarships were also provided by the fund. The halls were built with the help of grants and loans from the Miners' Welfare Fund which also provided assistance for their maintenance. The miners, however, had to provide much of the money themselves, what today would be called match-funding. This they did by means of a check-off system from their weekly wages which could vary from one old pence to five old pence a week.

Brynamman Public Hall

The Miners' Welfare Fund allowed extremely grand, large-scale halls to be built but there had been welfare halls before this, even though lack of money scaled down the miners' ambitions considerably. This was the age of the tin-shed halls, wood-framed structures covered in corrugated iron sheets. It goes without saying that timber-framed buildings are somewhat susceptible to fire and this was a fate that eventually befell many a tin-shed hall. When Brynamman's Miners' Hall burnt down on 15th December 1915, the twisted, smoking ruins revealed the vulnerability of such structures to stray matches. An enterprising photographer was on hand, however, to record the remains and turn the resulting photograph into a commercial postcard. Brynamman people purchased these postcards from local shops, eager to show their friends and familiies the catastrophe for themselves. Today we'd use a mobile phone to send a digital photograph, showing that while technology has advanced in a hundred years, human nature has stayed pretty much the same.

Ruins of Brynamman Public Hall, Dec 15th 1915It would take ten years to raise the money needed to replace this ramshackle ediface, but it was well-worth the wait, and the new hall of 1926 still stands today. Thanks to major grant-aided renovation in the 1990s, Brynamman Public Hall Cinema is open seven days a week with matinees on Fridays and Saturdays. (To see their website, with the current film programme, click HERE.)

Brynamman Public Hall and cinema traces its origins to 1926 but building work on the new Brynamman Cinema started in 1924 with seating for around 1,100 people. It was furnished throughout with tip-up seats upholstered in old gold corduroy. The stage was built 20ft by 60ft and had four dressing rooms below.

A lounge was situated below the library; it contained 12 armchairs and three settees where the miners could relax or play cards around several oak game and card tables. There was also a billiard room above the library. The opening ceremony was held on 15th May 1926. The cinema started with silent films until the 1930s, then the talkies. Today it also puts on live shows, allowing the children from Galaxy Theatre Arts to experience the thrill of performing on stage.

Brynamman Public Hall has continued to grow and kept up with all the changes the film industry has made over the years. This is due to the good work of the managers like Brian Harries, the present manager and projectionist, who joined in 1986, and the committee of volunteers who run the day-to-day business of the cinema.

Cwmlynfell Workingmen's Hall

Cwmllynfell Hall stood—and stood out—on the Black Mountain for many years after its opening on 4th September 1934 at a cost of £9,404. Until May 2001, that is, when it was demolished to make way for a new community hall built on the same site and opened on 7th May 2002.Gwaun Cae Gurwen Workmen's Hall

On March 31st 1928 Gwaun Cae Gurwen's old hall also burnt down, but this proved a blessing in disguise because the local Welfare Committee were now able to apply for a grant from the Welfare Fund and build the largest—and most expensive—hall in the Amman Valley.

The Gwaun Cae Gurwen Public Hall that was destroyed by fire in 1928. We can see that the disused Swansea church bought for £8 in 1898 was later refurbished, but it still falls short of the splendour that would emerge from the ashes in 1932 (see below). The Welfare Committee were nothing if not determined in their task: from the 1928 fire to the opening of the new hall in 1932 they held 63 meetings with an average attendance of 25 committee members. (Source: Amman Valley Chronicle 1st October 1932.) When the hall—and its gardens—opened for business on October 1st 1932 it had cost £14,888, compared to the mere £5,000 Ammanford Welfare Hall, opened the same day, had cost. The original tin-shed hall had been built in 1898 when a disused Swansea church, purchased for £8, was transported to the village where its wooden frame and tin-sheets were quickly redeployed for rather a different purpose than worship.

Welfare Hall and Gardens, GwauncaegurwenThe Gwaun Cae Gurwen Workmen's Hall, sadly, is also no more, having been demolished in February 1995 to make way for a clubhouse for the local rugby club, and a similar fate has befallen many of these halls elsewhere. The Gwaun Cae Gurwen Hall may have opened on the same day—October 1st 1932—as Ammanford Miners' Welfare Hall but would eventually succumb to the bulldozer's unwelcome advances, a fate Ammanford's hall managed to resist.

Cwmamman Public Hall, Garnant

Cwmamman Public Hall was opened on 19th February 1927 in Garnant at a cost of £12,000 on land donated by the local Gelliceidrim colliery. After several successful decades as a much-used asset, the Hall's use by the local community declined, its most recent use being as a snooker hall and club, and in 2007 it passed into the ownership of a London property company, since when it's been boarded up and derelict. But by March 2009 the building had deteriorated so dangerously that the local County Council were forced to issue a notice to the owners to make the building safe or demolish it. In January 2009 the police, bizarrely, had discovered that the empty and boarded-up hall was being used as a drugs factory, when 5,000 marihuana plants were discovered in the building. The two men who were found operating the drugs factory were later imprisoned.

Llandybie Public Memorial Hall

Part of the watershed of the Loughor and Amman rivers, the nearby village of Llandybie also shares the cultural and industrial history of the Amman valley. From the mid-19th century onwards, agriculture rubbed shoulders with industry in the form of coal mining and quarrying, which were once major sources of employment in the parish. Pencae'r Eithin, the last coal mine, closed in 1958 while limestone quarrying and lime production continued in a rapidly declining form until Cilyrychen Quarry closed in 2002.The other public hall in the area to reflect this industrial heritage is Llandybie Memorial Public Hall. £2,000 from the Miners Welfare Fund in 1924 enabled the hall to open its doors in 1925. The total cost was in the region of £4,300, the rest of the funding coming from donations, and the weekly deductions from local miners' pay.

It was given its name, which is unusual for a miners' hall, because it was dedicated as a memorial to the dead of WW1. A tablet with the names of the dead was erected inside the hall in 1933. Sadly, it was necessary to add a second tablet of names after WW2. A cinema projector was installed in 1946 and the hall showed films until October 1960. Before 1946 the hall was used mainly for theatrical performances, concerts, public meetings etc. During WW2 the hall was used for fund-raising events (with strict blackout observance, of course) and also became the HQ of the local Evacuee Committee, an Air Raid Precaution Centre, and was used by the Home Guard for training purposes. Also during WW2 the Old Vic Theatre Company performed at the Hall. In 1944 the National Eisteddfod was held in the Hall with local chapels and vestries being used for preliminary rounds.

The Hall also owned the adjoining bowling green, tennis courts, children's playground and car park, which were eventually handed over to the Dinefwr Borough Council in 1989, allowing the hard-working committee to concentrate on running the Hall. In 2007 grants totalling over half a million pounds enabled major renovations, including a side extension, to be made.The Halls Today

The trinity of mine, chapel and workmen's hall was more precarious than must have seemed all those years ago. At the base was the mine, whose workforce built and funded both the chapels and the halls. Take away the mines, and the whole edifice faces collapse, which is what has happened since the closure of every pit in Wales.As to the fate of these halls now, the contemporary Welsh language poet Grahame Davies eloquently, and elegiacally, writes:

The Workers' Hall could do with some work,

weeds are growing in the cracks of its grandeur;

and the slates of the roof have been stolen—

the slates of empty buildings

are one of the valley's last natural resources.Hall, chapel, club:

a society's essentials once,

are now shells, museums without visitors:

like old people whose children have left them.

The community no longer needs them enough

to look after them.[From the poem 'DIY', written and translated by Grahame Davies, in the Bloodaxe Book of Modern Welsh Poetry, published by Bloodaxe Books, 2003, page 393]

1. Introduction to Miners' Halls 2. Ammanford Miners' Hall 3. The Committee Man 4 Epilogue 5. Sources 2. AMMANFORD MINERS' WELFARE HALL

The Beginnings

The Welfare Hall and Institute in Wind Street, Ammanford had its beginnings in 1923 when a local committee drawn from Ammanford No 1 and No 2 collieries and Tirydail colliery formed the Ammanford District Welfare Association with the express purpose of building a hall. A grant of £1,000 from the central welfare fund, assisted by an overdraft, purchased the two freehold properties of Nos 9 and 11 Wind Street, next to St Michael's Church, at a cost of £2,000. The workmen of these three collieries were to contribute two pence a week until the debt was cleared.

The original shops of nos 9 & 11 Wind Street, demolished to build the Miners Welfare Institute in 1936. But what could not have been foreseen in those days of hope in 1923 were two major strikes in rapid succession. Despair and hardship soon followed in 1925 after h a four-month long strike in the Anthracite District which had Ammanford at its epicentre. And far worse was to follow in 1926 with the awful seven-month lock out of the General Strike. After these two dreadful years the three collieries that were meant to provide the funds for the enterprise were reduced to just one, with the permanent closure of Ammanford No 1 and Tirydail collieries as a result of the strikes. Even so, by September 1928, the overdraft was cleared and in 1930 the workmen of the Park and Saron collieries joined the scheme.

Now that the loans for the land purchase had been paid off the next task was to provide funds for the building work and in 1931 another bid for a loan from the central welfare fund was successful with £2,000 procured for the building of a hall.

The layout of the site itself, with its two halls, has puzzled observers, both at the time and since. The first to be built was the large and imposing cinema at the back of the site and the smaller, more modest, even plain, Institute was opened on the road frontage four years later. The Institute (at the front) housed the reading rooms, library, committee rooms, games rooms, public hall and caretaker's quarters. It should be noted that nowhere in the building was there provision for the drinking of alcohol—that came much later. The Institutes were conceived from the very beginning for the purposes of recreation, education and self-improvement only.

The Welfare Hall (the cinema)

The new hall was designed by a local architect Mr Owen J. Parry and built by Mssrs A. H. Bond & Co. of Swansea (later of Ammanford). The building, which cost just over £5,000, was based on a classic design of the time with an attractive facade in facing bricks with ornate terra cotta columns, string and plinth courses, all roofed in Caernarfon slates. The main auditorium seated 760 with 220 in the balcony and 540 on the ground floor. The interior was decorated in fibrous plaster mouldings in keeping with the fashion of the day.

When an application for a dramatic licence was made for the new hall, an objection was lodged by another cinema in the town, the Palace Cinema in the Arcade. The owner of the Palace, Mr P. F. J. Bosisto, offered the rather curious objection to Carmarthenshire County Council's licensing committee that Ammanford already had three establishments holding such licenses—the Palace Cinema, Poole's Pictorium, and the Ivorites Hall. The objection seems to have been that if Swansea, with its vastly larger population, had only two such premises, then Ammanford already had too many. The licensing committee were however favourable to the application and Ammanford suddenly had four premises licensed to hold dramatic performances.

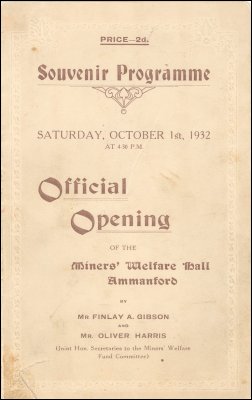

On Saturday, the 1st of October 1932, Mr Finlay Gibson, Secretary of the South Wales Coal Owners' Association, along with the Co-Secretary, Mr Oliver Harries, performed the official opening, supported by Mr James Griffiths (later to become the local MP). Other dignitaries attending the ceremony included Mrs Minnie Rees, Chairwomen of the Ammanford Urban District Council; Lt-Col. W. N. Jones; Major J. W. Bishop; Mr W. Lock Smith, Magistrates Clerk; Mr Eustace Llewelyn, Solicitor; Mr A. Davies, Manager of Lloyds Bank and, more surprisingly, Mr P. F. J. Bosisto, Manager of the Palace Cinema, who had so fervently opposed the issue of a dramatic licence not long before.

(Note: Lt- Colonel W. N. Jones and Major J. W. Bishop will be encountered in the essay 'The Origins of some Ammanford street names' in the 'History' section of this web site. James Griffiths can be found in the 'People' section).

Souvenir programme for the opening concert of Ammanford Miners' Welfare Hall, October 1st 1932 The opening concert must have been typical of the period, with its emphasis on culture and the light classics. To commemorate the event, Mr David Jeffreys M. E. presided at an evening celebrity concert in the Hall, to a capacity audience of local dignitaries and guests. Artists performing included a recitation "Wait a Bit" by Miss Beryl Davies; a solo by Master Harry Thomas, 'Where'er you walk' (Handel) and the 'Shepherds Dance' by the Co-op Children's Choir.

In the years to follow, though, the hall principally took on the role of a cinema. One week in the year was however reserved for the notable drama week organised by Ammanford and District Arts Club, when various amateur dramatic societies, mostly local but some from further afield, would perform a selection of plays in competition. This was a keenly and enthusiastically fought contest for the accolade of best performance, an event producing extremely high quality stage productions. The very first Drama Week was in 1948 and this lasted until about 1975. From personal memory, the author can remember one of the drama weeks around 1970 when the plays included Dylan Thomas's 'Under Milk Wood' (predictably) but also, and less predictably, a contemporary play by Peter Nichols called 'A Day in the Death of Joe Egg', about a young couple's struggle to bring up a severely handicapped child. A typical year was 1963, when plays included Arthur Miller's 'All My Sons' and Keith Waterhouse's 'Bill Liar', with a dramatisation of 'Anne Frank's Diary' being judged the overall winner of the competition. Some plays were brought down from the Edinburgh Festival Fringe where key figures in the Ammanford Drama Week organisation would visit on scouting missions for the very latest plays. The staple diet of the week, though, were the classics of amateur dramatic societies—Oscar Wilde, J. B. Priestley, Noel Coward, Terence Rattigan, Chekhov and the like, and including some plays by home-grown Welsh dramatists. In addition to the annual drama week, Ammanford Arts Club staged their own play at the Welfare each year.

The cinema projectionist for a time was D. Brin Daniel, who will be encountered in 'The Miner's Tale' in the 'People' section of this web site. The first and best known projectionist, though, went by the nickname of 'Dai Magic Lantern', and who was also an amateur painter. His name still lingers on after his earthly passing through his paintings which hang in the club to this day. Although his name was David Williams he proudly signed his paintings 'Dai Magic'.

The march of time, however, is usually indifferent to tradition and soon had its own ideas for the Welfare Hall. The introduction of television brought a more passive form of entertainment which could be experienced at home, and the growing ownership of cars allowed people to travel further afield in search of diversions. This created major problems for theatres and cinemas throughout the country, and the Welfare Hall was no exception. Unable to operate as a viable unit, the safety curtains were lowered for the last time in the mid-1970s. The building after this was utilised for other forms of leisure and entertainment, all of which met with limited success.

In a survey carried out in 1994 by CADW (the organisation responsible for conserving Welsh historical monuments), the Welfare Hall was listed as a Grade II Building, being described as a "powerful example of inter-war architecture and as the most prominent memorial of the coal-mining history of the area". Ammanford is the only Welfare Hall in the region to acquire listed status and indeed one of few in the whole of South Wales to do so.

1997—A new start

By arrangement with the Trustees, in 1997 the Carmarthenshire County Council entered into a long-term lease of the premises, obtaining financial aid in the form of grants under the Welsh Office Strategic Development Schemes to carry out extensive external refurbishment of the property. This included £97,000 from the national lottery. Further proposals are outlined involving conversion of the building into a multi-functional community centre, with facilities for youth activities; craft workshops; conference rooms with video and visual aid screens; theatre facilities; computers, including an Internet café; and a dance hall. As of 2001 a cinema projector has been added to the Welfare Hall restoring it to something like its former use. Amateur boxing bouts have also been organised at the hall.

The upper floor has been converted into the Ammanford Miners' Theatre by extending the floor of the former balcony forward to meet the original proscenium, the upper half of which is the only part now visible. The rear half of the original balcony has been retained and provides fixed raked seating. The space is now mainly used as a theatre with various productions staged throughout the year but it is versatile enough to cater for live music and there are weekly jive dancing classes held. In 2001, a projector and portable screen were purchased so that it is now possible for occasional film shows to be put on and an annual film festival is held in May. The Miners' Theatre has a capacity of 222 and is run by Carmarthen County Council as part of Carmarthenshire Theatres, the others in the group being the Lyric Theatre and Cinema in Carmarthen and Theatre Elli in Llanelli where there are three cinema screens (the former Odeon/Classic/Entertainment Centre).

[The Welfare Halls and Institutes of the Swansea and Amman Valleys in the South Wales Coalfield by John Skinner of Ystalyfera Heritage Society.]

Ammanford Miners' Theatre's website can be found HERE.

The Welfare Institute

Having completed the cinema project in 1932 the Miners' Welfare Committee now turned to the provision of reading rooms, a library and other recreational facilities—the Welfare Institute. By 1936, a substantial building, based on a more modernistic style with a less grandiose design than the Welfare Cinema, was erected on the site of the old business premises, immediately fronting onto Wind Street.

The library was stocked, like the library of Ammanford Social Club (the 'Pick and Shovel'—click to see the essay in this section) mostly from the Left Wing Book Club which recommended books on a monthly basis. Many of these books were self-improving books on history, politics, philosophy etc, but a full range of reading material was available. Like the library of the 'Pick and Shovel', these books disappeared during major conversions in the 1960s.

Downstairs was a reading room providing most of the daily newspapers, magazines and journals, all held in large leather holders with a metal spine down the middle to hold the reading material in place. The newspapers and magazines were laid out on a shelf running around the room where readers sat on tall stools to browse them, all rather old fashioned now, but that was how it was done then. This author can remember first reading the Manchester Guardian and New Statesman in regular forays into the reading room during school dinner breaks, wet Saturdays and school holidays in the early 1960s. This was of course when there was no money to spend in the Lucania Temperance Billiard Hall (The Luke) or on any other more productive diversions. A character known as 'Harry the Tramp' would often be encountered in the reading room, usually there to shelter from the weather or just to while away time, so no difference between us there. The Welfare's reading room became a bar after the conversion of 1965, its heady smell of newsprint and damp being replaced by tap-room aromas instead.

The Welfare Institute was an significant addition to the town's intellectual and cultural life, especially the 'Minor Hall', a large room capable of seating 250. (It was called the minor hall to distinguish it from the Welfare Hall, which was the major hall in capacity.) Many distinguished people were invited to speak on cultural, industrial and political issues of the day; the Member of Parliament for the area, the Right Honourable James Griffiths, served his political speaking apprenticeship in this hall.

Twice weekly, without charge, the accommodation was thrown open to young people who belonged to a youth club, overseen by clergy, to hold dances, debates, plan football and cricket matches and hold table tennis competitions. It was also a meeting place for various ladies' guilds, angling associations, whist clubs: a building readily made available to the public for a wide variety of uses.

While the coal industry was dwindling in size due to government pit closures, the financial upkeep eventually outstripped the miners' weekly contributions and so other sources of income had to be found. In March 1965, a planning application came before the local authority to convert the premises into a licensed club. The reading room and library became bars; the books, so carefully accumulated over thirty years, were disposed of and the 'Minor Hall' was transformed into a concert and bingo hall. This, though, was the route many working men's institutes were forced to take or disappear completely. That's the position of the Ammanford Welfare Institute to date: predominantly a drinking club, but still in use for trades union and political meetings, while the former billiards room, closed in 1965, was imaginatively converted into a mining museum in 2005. Still, given the fate of many other workmen's halls throughout Wales and the rest of the coalfields, it's a massive achievement that both the Welfare Hall and the Welfare Institute have survived into the modern era, where sedentary entertainment at home seems to be the preferred option.

Royal Visit to the Miners' Welfare Institute in 2008

In November 2008 the Welfare Institiute played host to an unusual and rather more illustrious visitor than it was accustomed to receiving—a king, no less. Crowds of cheering school-children gathered in Ammanford to greet His Majesty King Letsie III, monarch of the tiny south African country of Lesotho, as he visited the town. His Majesty's four-day visit to Wales had already taken him to the National Assembly, BBC Wales studios, and twinned schools, St Cenydd's School Caerphilly and Trewen Primary School, before arriving in Ammanford. Volunteers at Ammanford's 2ACTIV8 centre welcomed the King to their alternative lifestyle centre on Wind Street which helps people with learning difficulties gain the skills they need to enter employment. Along with 90 invited guests and local digniaries His Maj was afterwards given a royal reception at the Miners Welfare Institute. At his own request that the banquet should consist of local Welsh dishes, he was entertained with fare that included home-made cawl and faggots and peas! So far as anyone is aware, faggots and peas have never been described as a meal fit for a king, but perhaps that may now change.

The Ammanford District Miners Welfare Association has over the years contributed generously, both culturally and financially, to the community, a contribution that is highly appreciated and respected by the town's folk. In 1948 the Welfare Association built a tennis court in Ammanford Park for the use of the townspeople and for a while the libraries of the Welfare Institute and the 'Pick and Shovel' rivalled the rather limited library provided by the County Council.

1. Introduction to Miners' Halls 2. Ammanford Miners' Hall 3. The Committee Man 4 Epilogue 5. Sources 3. COMETH THE HOUR, COMETH THE COMMITTEE-MAN ...

All working men's clubs are run by a committee, elected by the membership to act on their behalf. Whether deserved or not, these committees have acquired a certain reputation, not always a favourable one. The inevitable men-only, elderly profile of a typical committee hasn't helped their image down the years, and until recent times working men's clubs even excluded women from their membership. (Many still do; conversation in these places will roam over just about every subject under the sun, but women's equality isn't often one of them.) Our working men's clubs date mostly from the 1920s and 1930s, and until recent decades they were fiercely men-only strongholds. Most clubs have since relented and now allow women through their doors, but their spending power, not consideration for their rights, has often caused this change of heart, and many clubs will still not allow women the voting rights that come only with full membership.

An aging membership, too, has earned many a club the nickname of God's waiting room, often with good cause. This can result in friction between younger and older members, with the older ones unable to spot that the world has changed considerably since their own youth. It's amusing to think that today's committee men, usually heard complaining bitterly about youthful disrespect, are the very same people who earned the contempt of their own elders when they were young themselves. We may complain that things aren't what they used to be, but then they never were. We would do well to ponder the grumblings of the elderly shepherd in Shakespeare's play The Winter's Tale, written about 1610, as he utters the heart-felt wish: "I would there were no age between ten and three and twenty, or that youth would sleep out the rest; for there is nothing in between but getting wenches with child, wronging the ancientry [ie the elderly], stealing and fighting." (The Winter's Tale, act 3, scene 3.)

One person for whom club committees aren't exactly paragons of modernity is rock musician Deke Leonard from Llanelli, member of various local bands during the sixties and co-founder of the Manband from 1968. In his autobiography, "Maybe I should have stayed in bed?", he provides an amusing account of a 1960s encounter with the committee of nearby Cwmllynfell Working Men's Club at the top of the Amman Valley. Whether this is typical of all committees we couldn't possibly comment:

We were booked to do a Christmas gig at Cwmllynfell Workingmen's Club. Cwmllynfell is an arrondissement of Upper Cwmtwrch, a place I thought was a fictional town invented by Welsh comics to symbolise the outer limits of civilisation, but apparently it was real. It was new territory for us so our agency, Verney Ley Enterprises, had agreed on an introductory fee of £14. Verney would take his ten per cent, leaving us with £12. 10s. Hardly a fortune but not bad for a Thursday gig.

....We were welcomed by a committeeman. Every Welsh workingman's club is run by a committee. Apart from monthly committee meetings the members are never seen together, thereby making it nigh-on impossible to determine how many there are at any given time. During the course of the evening you will have to deal with at least four of them, all, apparently, in supreme command. They are always men and they are always elderly. They are secretive by nature and defensive by habit, and usually subscribe to the view that the general public are a necessary evil. They didn't understand this new-fangled, rock'n'roll razzmatazz but their younger patrons demanded it, so they had to provide it, but that didn't mean they had to like it. They regarded all bands as the spawn of Satan, somewhere, on the social scale, between arsonists and child-molesters. We were barbarians at the gates, and they treated us with an almost paranormal caution. This one was typical of the breed.

....'You're not going to play too loud, are you?' he said welcomingly. 'No,' said Wes. 'Some clubs complain because we're too quiet.'

....'That's all right, then,' said the committeeman, confirming that irony had yet to reach this far up the valleys. 'There's the stage,' he added, pointing at a minuscule platform, a foot-high, dominated by a large Christmas tree, covered in lights and topped-off with a fairy. 'You haven't got lots of equipment, have you?'

....'No,' said Wes. 'We won't be using our amps tonight, we'll only use one drum, and we'll whisper the vocals. OK?'

....'Good,' said the committeeman, obviously relieved. Maybe we weren't as bad as he'd expected. Maybe it was time to be magnanimous? 'Do you want me to move the Christmas tree over to give you a bit more room?' He smiled for the first time.

....'That'd be nice,' said Wes. 'By the way, have you got any daughters?' Yes,' said the committeeman 'One.'

....'Is she coming tonight?'

....'Yes,' said the committeeman, 'Why?'

....'No reason,' said Wes, rubbing his hands together and giving a leer that Bluebeard would have been proud of.

....The committeeman, eyeing Wes suspiciously, moved the Christmas tree over to side of the stage and hurriedly left the room.

....'I'm just going to make a phone call,' he said as he left.

....'I bet he's going to warn off his daughter,' said Wes ...[Deke Leonard, 'Maybe I should have stayed in bed?', Northdown Publishing, 2000, page 81. More details of this book, plus another volume of autobiography, 'Rhinos, Winos and Lunatics', can be found on Deke Leonard's website: www.dekeleonard.com]

The whiff of financial scandal has occasionally been detected from inside committee rooms, too, and not a few clubs have witnessed a committee man, or bar steward, or both, disappear on an enforced holiday at Her Majesty's pleasure. The old joke of a club offering a month on the committee as first prize in its raffle isn't that far from the mark sometimes. But if this shows anything at all, it shows that working men's clubs are part of society, not outside it, and if they've changed radically from the 1930s, that's because the world has moved on in the intervening years. We may not like those changes, and yearn for a more innocent time, but the clock doesn't tick its time backwards. The world before there were 200 TV channels, DVD and video players, computer games, Internet entertainment, two-car households, charter holidays and theme parks, is dead and buried, brought back to life only in memory, and today's working men's clubs fulfil a different role in their local communities than their predecessors.

1. Introduction to Miners' Halls 2. Ammanford Miners' Hall 3. The Committee Man 4 Epilogue 5. Sources 4. EPILOGUE

Bryan Martin Davies is a poet who won the Crown Poetry Prize in the National Eiseddfod of 1970 held in Ammanford. As he is from Brynamman, it is somehow appropriate that someone who was born where the river Amman starts should win Welsh poetry's highest accolade in the place where the river ends. Here is a translation of one of his poems which casts a nostalgic glance at the workmen's halls of the Amman Valley, all the more poignant for the fact that the world he evokes has now vanished beyond recall. The poem manages to sum up in just a few lines a generation of cultural life in the Amman Valley, where the halls served as picture houses and venues for live theatre, eisteddfodau, operas, operettas and concerts.

Halls

You were our one and ninepenny pleasure palaces

in the villages of the Valley

offering your celluloid narcotics every night

in your velvet dusk,

and taking us on three-hour trips

far from the grip of the Black Mountain.

In you we sank,

extinguishing the lamps of our cares

promptly at seven,

and letting the silver needle of the screen

inject the warm forgetfulness

into the veins of the brain.You were the Wednesday night theatres of our winters in the Valley

when we forgot the America of our dreams

after your stages had turned into Welsh kitchens,

and when the talented old companies of Dan Mathews

made puppets of our emotions,

compelling them to dance to the strings of their skill.

You were the warm courts

of our harmless eisteddfodau and old-fashioned concerts

giving your patronage

to the rural culture which lasted in spite of iron and coal

in the villages of the Valley.Baroque boxes, halls of red brick and grey plaster,

posters of blue and yellow shouting welcome,

your colours continue to warm

the canvas of memory.Bryan Martin Davies

Translated by Leslie Richards

Reprinted from "A Carmarthenshire Anthology";

Edited by Lynn Hughes; published by Christopher Davies, 1984.Note: a brief history of the town's other working men's club, Ammanford Social Club, or the 'Pick and Shovel', as it's better known, can be found in this section of the website, or click HERE.

5. SOURCES

The Amman Valley Chronicle, 23rd February 1927 contains an article about the opening of Cwmamman Public Hall, Garnant. The Amman Valley Chronicle, 1st October 1932, has a lengthy report on the opening of Gwaun Cae Gurwen and Ammanford Welfare Halls. Ammanford: Origin of Street Names & Notable Historical Records by W T H Locksmith, published in 2000 by Carmarthenshire County Council, also has information about Ammanford Miners' Welfare Hall and Institute. The Welfare Halls and Institutes of the Swansea and Amman Valleys in the South Wales Coalfield by John Skinner of Ystalyfera Heritage Society has provided valuable material about the other Halls in the Amman valley.

1. Introduction to Miners' Halls 2. Ammanford Miners' Hall 3. The Committee Man 4 Epilogue 5. Sources Date this page last updated: August 24, 2010