AMMANFORD ANTHRACITE STRIKE 1925"When coal was king and

the valleys were the throne"Communities of all sorts have their legends, mythologising a past conveniently too far back to be confirmed by living memory or too undocumented to be given the approval of history. Many of our more enduring legends, it's true, have some basis in fact, but wish-fulfillment is usually the motive for clinging onto many of them. They hold up a mirror to the past, sort of, though distortions abound and the faces we see may not hold up in the identity parade of history.

One of the more intriguing legends from Ammanford's past, at least for those very few left who are old enough to remember or those younger ones keen to find out, is the Anthracite Strike of 1925. Often confused with the General Strike of 1926, the stories told over a few drinks in working men's clubs of riots on Pontamman bridge, hordes of outside police billeted in the town and hundreds thrown into prison, seem more a product of that defective process of memory than a record of fact.

And yet the story, once research has sifted fact from fiction, is as powerful as if it had been a product of a novelist's imagination. It was a momentous incident in Ammanford's past. And, with hindsight, it was a dress rehearsal for the General Strike of 1926 of which countless books have been written and which has all but obliterated those Summer days in Ammanford back in 1925.

But the past is another country: they do things differently there:

"Those were the days when coal was king and the valleys were the throne. For beneath the rugged mountains there was coal in abundance – steam coal for the navy, coking coal for the furnaces and anthracite coal for the hearth. And as the cry went out for coal and still more coal, the roads to the valleys were crowded with men in search of work and 'life'. They came from the countryside in the North and the West of the Principality and the shires across the Severn. And as they came they brought with them their way of life – the chapel and the choir the Rechabite 'tent' preaching abstinence from drink, and the pub, the rugger ball and the boxing booth – all mixed up together. And as they settled in the valleys the cottages climbed even higher up the mountainside until the mining village looked like a giant grandstand.

.....The life of a collier was hard and brittle. The day's toil was long and perilous. Everyday someone would be maimed – and every year some valley would experience the agony of an explosion. Yet in spite of it all or, perhaps even because of it all, the men and women who came to the valley created a community throbbing with life. Thrown together in the narrow valley, cut off from the world outside, they clung together fiercely, sharing the fellowship of common danger. Life in the valleys has a magic of its own, and to us who grew up in the glow of its fires there comes a nostalgic longing – 'hiraeth' as they say in our mother language – of the fellowship of long ago." (Jim Griffiths: Pages from Memory, London 1969, p27)So wrote Ammanford's most famous political son, Jim Griffiths, the former Betws miner who was to become a cabinet minister in later Labour Governments. Before he was elected to parliament in 1936 he was a full-time union official in the forerunner of the National Union of Mineworkers, the South Wales Miners Federation – popularly known as the 'Fed' – and which was a major actor in the events of 1925. For although we may wander through life as individuals it has been through our organisations that we have progressed, if that is the appropriate word, through the ages.

Jim Griffiths again -

"Transplanted from the quiet of the countryside into the turbulent world of industry, the worker needed a defence against the harsh realities of his new life and he found it in the union – the 'Fed'. The Federation was not only a trade union it was an all-embracing institution in the mining community. In the pits it kept daily watch over the conditions of work, protecting the men from the perils of the mine, caring for the maimed and the bereaved, and providing the community with its libraries and brass bands and hospitals and everything which helped to make life bearable and joyous. In the work and in the life of the community the Federation was the servant of all." (Jim Griffiths: Pages from Memory, London 1969, p27)

And the mine owners who were to provoke the strike of 1925 also had their organisations, in the form of two Combines of mine owners – the United Anthracite Collieries (UAC) and the Amalgamated Anthracite Collieries (AAC) which, by 1925, had slowly but surely bought up most of the mines in the anthracite district of Carmarthenshire and western Glamorgan. Control of virtually the entire anthracite industry was in the hands of these two trusts formed in 1924.

But what caused the feverish activity of 1923 and 1924 that saw most of the small mines of west Wales bought up in bulk by these two combines? By now International events were in motion which were not only to explain these goings-on in remote west Wales but woud also foreshadow what history now calls World War Two.

In 1923 French military forces occupied the Ruhr coalfield of Germany. This made the years 1923 and 1924 in Wales a prosperous oasis in an otherwise industrial desert. The reduction of coal from the Ruhr led to an increase in coal exports from South Wales and gave a boost to coal exports nationally as it did to other coal exporting countries of Europe and America. It would not be too far-fetched to suppose that this was the purpose of the Ruhr occupation. And it would not be too far-fetched either to suppose that the United Anthracite and Amalgamated Anthracite combines went on a shopping spree in the western valleys of Wales to cash in on the boom in coal exports.

But then in 1925 the Ruhr coalfield was freed by Germany and a slump followed the earlier bonanza as its coal came back on the market. The competition for the export trade not only reappeared but was intensified by a policy of subsidized port prices. The organisation created by the German coal owners was able to sell at reckless prices, as its export coal was subsidised by up to twelve shillings (60 pence) per ton (the pithead price of British coal was about one pound per ton in 1924 – a huge subsidy indeed for German coal). There was also competition from the Baltic markets from subsidised exports coming from Poland. The final blow came when Churchill decided to bring Britain back onto the gold standard and which had a dramatic effect on the exchange rate of sterling.

The cumulative effect was that coal output fell by 24 million tons in 1925 compared with 1924. The pithead price of coal dropped from 19/9 (99 pence) per ton in 1923/24 to 14/1 (70 pence) per ton in 1925.

These statistics may numb the brain not accustomed to higher mathematics, but the reality in human terms was that pits closed and the valleys were stricken by economic paralysis as they filled with men without work and families without means.

What did the British government do about this? They could have subsided coal as the German and Polish governments were doing. But that was not the option they chose. The General Strike started in May 1926 because the Conservative government actually ended coal subsidies, leaving the coal owners free to reduce wages and lengthen the working day. "Not a shilling off the pay not an hour on the day" was the slogan adopted by the mining unions for the General Strike.

We begin to see now what the combines were up to. They'd enjoyed massive profits in 1924 and instead of thanking the miners who'd actually dug the coal out and made these profits possible, they tried to make them pay for the crisis in the world economy. It wasn't British or German workers who fired off the shots that started this grim trade war, and which was to escalate by 1939 into a world war: it was the owners. But it was certainly British and German workers who paid the price in financial and human terms throughout the decade of depression that was to follow.

Before these two combines bought up the western coalfield, lock stock and barrel, each mine usually had a single owner, often a local farmer who'd discovered coal on his land or even 'self improved' former miners themselves. The coal that was torn out of the ground by the men – and sometimes women and children – may have kept the coal owner and his family in a standard of comfort and prosperity unknown to his miners but he was generally content with his lot. Indeed, he was usually a part of the community, often attending the same chapel or church as his workforce.

With these economic developments in the early 1920s, the human contact between owner and miner was severed. A working anthracite miner of the period, D.J.Williams of Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen (who later became the Labour M.P. for Neath, 1945 - 64) wrote lucidly of the situation:

"The growth of these powerful Combines effects a complete revolution in the relations of capital and labour in the coal industry. Time was when the colliery worker knew his employer personally. In those days, it was the custom of the owner himself to come round the faces to consider allowances, prices, special job rates, and to meet in person the workers end their representatives. Such is not the case now. The old relations of persons have given way to the new relation of things. The Combine is a vast machine, and the worker is merely a cog in it. He does not know his employers; probably he has never seen them. But the struggle between labour and capital still goes on, only it is now fought in a more intensive form. It is now a struggle between workers – through their organization – and the vast unit known as the Capitalist Combine. (Source: Hywel Francis 1973: "The Anthracite Strike and Disturbances of 1925", Llafur I.2 (Journal for the Society for the study of Welsh Labour history).

When several hundred anonymous shareholders own a mine instead of a few; when they are all clamouring for a return on their investment – where, then, does the extra money come from? If the cake is the same size then how do more people get a slice of the same size? The answer was simple – reduce wages, lengthen working hours, make men redundant and force those left to work a longer day and week to produce more coal. Or so the coal owners thought. But they reckoned without the 'Fed'.

We get a glimpse of what things were like before the arrival of the combines by the prices that miners were charged for house coal in 1920 and before the likes of Sir Alfred Mond and A F Szavarsey entered the scene. Each colliery was totally different as the following prices show -

Ammanford No 1

Quantity – 1 tram of large as it comes to the bank. Price – 7/1 per ton. Those eligible – householders, families in apartments and war widows. Lodgers – 1 tram per two months, 10 shillings per ton. Sons whose fathers do not work in the colliery treated as lodgers.Ammanford No 2

Quantity – 1 tram per lunar month. Price – 7/1 per ton, 4¼ per hundredweight (haulage extra). Those eligible – householders or breadwinners, including those living in apartments. Lodgers – 10 shillings per ton (haulage extra).Tirydail

Quantity – 1 ton 1 hundredweight per month. Price 7/3 per ton. Those eligible – householders, breadwinners and families in apartments. No coal supplied outside cartage area.Pantyffynon

Quantity – 1 load per lunar month. Price 6/8 per ton. Those eligible – family dependents. Outside cartage area – delivered in truck, wagon and dues extra.These changes in the pattern of mine ownership, along with the changes that this situation introduced into the field of industrial relations, presented the miners with new problems of management practices which were alien to the anthracite coalfield with its long-established customs and practices. Disputes had occurred in the past but in relation to the eastern coalfield the anthracite district had been comparatively peaceful.

The coal owners' combines saw these customs and practices in the anthracite district as an obstacle in the way of their drive for profitability. They saw the men who worked the mines and their families, not as human beings, but as commodities who could be bought and sold on the open market like cattle. And they saw their organisation, the 'Fed', not as a legitimate body representing the interests of the miners in counter-balance to the organisation of the mine owners, but as an even bigger obstacle in the way of profits.

The chairman of the United Anthracite combine, F A Szvarvasy, even stated this quite openly in his address to the first annual meeting of the shareholders of the United Anthracite Collieries Ltd in 1924 -

"Regarding this colliery (Ammanford No 1) it seemed evident at the time the present Board of Directors took control that the working conditions had to be rearranged before satisfactory profits could be made".

Immediately the United Anthracite Collieries took over Ammanford No 1 colliery where the 1925 strike began, a new manager was appointed and there began a series of intermittent struggles over such questions as the combine's attempt to eliminate the New Year's holiday, Good Friday holiday, the short Saturday shift and house coal for lodgers. Many such customs were lost because there had been no written agreement with the previous owner.

Then, during 1925, the UAC created a situation at Ammanford No 1 Colliery by challenging the rights of the important custom of seniority rule, which protected the workmen from victimisation from management. This custom, the right of the "first in, last out" rule of employment within pits, provided a degree of security of employment. It ensured that whenever there were redundancies there was a fair and understandable procedure to follow. And, the owners couldn't use redundancies as an excuse to rid themselves of union activists. Without the seniority rule mine owners could pick and chose whom they laid off; with the rule all men were protected by their date of employment at the pit with those most recently employed the first to be laid off.

"From the most quiet natured miners to the strong, stormy and boisterous elements, all were equal within the pit under the protection of this custom".

This was particularly important in the Amman valley because much of the coal was exported to Canada. Three months of the year the St Lawrence river froze over completely and no coal could get through. Many Amman Valley pits shut down and miners had to seek temporary work in the eastern valleys to tide them over this period. And in the summer months too, when the warm weather reduced the demand for coal, miners were allowed to migrate to the eastern valleys and return later to reclaim their old work places.

The seniority rule ensured that, during the temporary lay-offs, all men were treated equally and laid off in order of seniority. And when they returned to work at their home pit they were also reinstated in order of seniority. But – and it is a big but – the union had to be strong enough to make sure management abided by the agreement. The problem arose at Ammanford No 1 when the new management refused to acknowledge and implement the seniority rule.

The incident that actually sparked the strike off was, at the time, seemingly trivial. The custom whereby a father could have his son to work with him so long as his regular partner (or 'butty') would agree to work in another place was the source of friction and a man, Will Wilson, was dismissed at the end of April 1925.

The Ammanford No 1 lodge, and four other Ammanford pits, decided to strike over this issue and took the matter to the 'Fed'. Within a short time the whole of the Swansea district anthracite miners were out on strike. There followed a period of riotous and bloody confrontation between the miners picketing the collieries and the police, most of who had been imported from outside the valley and billeted locally.

Finally, one evening, groups of workmen visited each pit in the Amman and other valleys and, after some troubles, picketed the men out of every pit in the Swansea district. By July 14th, the second day of the all-out strike, all miners were out except at two collieries in the Dulais Valley and the Vale of Neath. These, it was decided, would be picketed out. Ammanford miner Ianto Evans (and, incidentally, father of future Welsh Rugby Union President Ieuan Evans) was one of these. He remembered the scene in 1932:

"A mass meeting was arranged at Glanamman football ground and it was a glorious sight, thousands of workers being present and by this time news had come through that these two collieries were working. Eventually a letter from a contact in the Dulais Valley was handed to the Chairman, Arthur Thomas, with the information regarding the situation. A resolution was moved that a demonstration proceed that night to meet these workmen going to work the following morning. The resolution was carried unanimously and a rush was made to Ammanford to get a crowd together as no prior arrangements had been made. That night about 400 strikers left Ammanford at 10.40 pm led by the Ammanford brass band and proceeded up the valley where they picked up the Cwmaman section, headed by their brass band, then to Gwaun Cae Gurwen and Brynamman, with another band each. Through the Swansea Valley the crowd gathered like a snowball and by the time the procession reached Ystradgynlais Common it was 15,000 strong. They continued to march through the night until they got to Crynant in the Dulais Valley, 21 miles from Ammanford."

Decades later older people of the town and valley could recall their fathers coming home after the march and bathing their blistered feet. One such is Mrs Irene Jones, whose family was living in Gwaun Cae Gurwen at the time of the 1925 strike, [it is known locally as GCG or the Waun] and who has given us her memories.

Mrs Jones, by the way, must be complemented on the accuracy of her memory as she recalls events 67 years after they happened. Everything she relates below, described in March 1992, can be substantiated from newspaper accounts of the time, particularly the Llanelli Labour News, the official weekly newspaper of the Llanelli Labour Party, which carried a detailed, week-by-week, report of the events as they occurred during 1925 and 1926.

"I remember miners were walking to Crynant because some miners up there were working and the walk was to protest and stop them reaching the pit. I think the march started from Ammanford, picking up other miners on the way, meeting the rest on GCG cross, walking all the way through Brynamman, Cwmllynfell, Ystradgynlais and onto Crynant to meet the train which was to take the miners there to work.

...... They created a lot of disturbance. When they returned they could barely walk as their feet had cuts and blisters. They were exhausted. David Daniel Davies, known as Dai Dan, was taken to jail during the strike. When he came out the GCG band were playing on the Waun square and the whole village was out to welcome him and a grand concert was held at the public hall. I sang at the concert. I was nine years of age.

...... Soup kitchens were held for miners' children. The younger children were in the vestry of Carmel Chapel and the older children were in the vestry of Siloh chapel. The children had a string around their necks to hold the spoons in case they lost them. At dinner time the children would run from school to the soup kitchens. Children whose parents were not miners and not out on strike were crying because they could not go to the "tea party".

...... Concerts were held to raise money to pay for the food. Also, some of the men went from place to place singing on the streets to get money.

...... Shop keepers were very kind. They gave food without payment to the ones that did not have money to pay. They knew they would be paid by installments after the strike was over. There were no supermarkets then, only family shops and they knew their customers.

...... Some people were lucky; they kept chickens and pigs at the bottom of the garden and had plenty of vegetables in the garden. Everyone helped one and other I don't think any one starved. The community pulled together.

...... I remember riots at Betws colliery. A bus full of policemen came down from Glamorgan with batons. People were frightened to go out of the house.

...... In those days we used to go on picnics to the common land on the Waun, we called it the "patches", to collect waste coal. They could not prosecute as it was common land and they used to dump the "sbwriel" [the Welsh for 'rubbish'] on the common.

...... During the 1925 strike I remember two men coming down from the Maerdy colliery in the Rhondda. They had walked all the way, and they were singing in the street for money. What they didn't realize was that they were my mother's first cousins and when they found they were related to us the two men cried with shame that they were begging in the street in front of their own family. They were taken in by my grandmother to have food and a place to stay for a few nights".Just one year later the very same people, even those who kept chickens and pigs, would not be so lucky. The General Strike and lock out was to last seven months, not eight weeks, and would stretch quite a while beyond the warm summer months, to decidedly chilly November in fact. And remember, anthracite miners would have already had a strike just a year earlier. And the families of those 58 jailed would have had several more months without wages while their bread-winner was in jail.

But more importantly they would be returning to work, not after a morale boosting victory, but after a crushing and humiliating defeat not of their own making.

What was even more astonishing was that while the TUC awarded strike pay for the nine days duration of the General Strike to all the other unions who came out on strike, the miners received nothing. A General Strike, which was called in defence of miners' living standards, ignored the miners completely. The TUC General Council (its 'cabinet') even excluded the miners' delegates from most of the negotiations and decision-making meetings, usually secretively but often blatantly.

But that procession one year before, in 1925, must have been quite a sight. It certainly caused intense excitement as it proceeded along the valley, with the brass bands and the hymn singing as they marched through the night, the cigarettes twinkling in the darkness providing the only light. After several incidents as well as some momentous open air meetings along the way, the whole of the Dulais valley miners joined the strike.

And a week later, on Tuesday 21st July, the whole process was repeated in reverse when 15,000 men marched down the valley to a mass gathering on Ammanford recreation ground. From now on matters became so serious, with skirmishes and incidents at dozens of collieries in the district, that it was drawing national attention from a government already making preparations for a general strike, and with questions being asked in the House of Commons.

On one day alone, July 30th, there were riotous disturbances simultaneously at Ammanford square, Ammanford No 2 colliery where there was a police baton charge, at Betws and also at Wernos, Pantyffynnon and Llandybie collieries. And the major battle was yet to come, the so-called 'Battle of Ammanford' which occurred on August 4th.

That day, two hundred Glamorgan police, who were billeted in Gwaun Cae Gurwen brewery, were ambushed on Pontamman bridge when they came to a picket of Ammanford No 2 colliery. The police nevertheless reformed and systematically drove the strikers back into Ammanford. The "battle" persisted from 10.30 pm until 3.0 am.

The UAC eventually gave up the struggle and recognised the seniority rule within the anthracite district. No doubt a campaign to spread the dispute throughout the whole of south Wales was not unconnected with the owners' decision to give in. The miners returned to work on August 24th. They'd won the struggle – but they lost Ammanford No 1, for this pit was closed by the UAC for good in reprisal. However, as all the men from Ammanford No 1 were to be relocated to other nearby collieries, this must be seen as a victory. The Ammanford miners were prepared to sacrifice their pit and to endure short-term unemployment in order to save the seniority rule. In that sense the agreement came to be seen as a momentous victory.

But retribution was to follow. The incidents during the strike resulted in a high number of local people being committed to trial for unlawful and riotous assembly, with 198 in total prosecuted and 58 miners being finally imprisoned. There were wild scenes of excitement and enthusiasm throughout the trials and whenever a prisoner was released. Every day of the trials, bus loads of miners and their families travelled to Carmarthen to cheer the prisoners and sing hymns and the 'Red Flag' outside the courtroom while several brass bands accompanied them. A shilling a day was levied on Ammanford miners to allow the payment of a minimum wage to all the prisoners' dependents. £10,000 had to be borrowed from the Fed to pay for legal and other costs.

Yet the arrested miners never expected justice from the grand jury called together to judge them. A jury that included two colonels, two majors, a captain, a knight, a parson and Lord Cawdor's estate manager hardly constituted a jury of their 'peers'. In their upper-class eyes these men were just miners, the 'great unwashed' – and trade unionists to boot – and they were sentenced accordingly.

The sentences passed on these 58 miners, ranging from one to eighteen months, outraged the sense of natural justice of the miners and their communities. One young miner from Cwmtwrch, the sole supporter of a widowed mother and eight children, was so badly injured by police truncheoning about the head that he never worked again as a miner. Yet no police were charged. And at a Cross Hands protest meeting Jim Griffiths captured the feelings and social attitudes of the community:

"Let them compare young Joe Rainford getting twelve months while Hayley Morris only got three years for ruining young working class girls (applause)".

There was a wide body of opinion deeply moved by the sentences imposed upon those fifty eight colliers who spent the Christmas of 1925 in prison. There were many who would have endorsed the feelings expressed by Gomer M Roberts in a sonnet addressed to the men who were imprisoned that Christmas. Gomer Roberts was an Ammanford miner who had won a scholarship, with the help of money raised by local miners, to become a chapel minister -

"Mae arfaeth fawr

Tu ol a welwn ni – adferwch hoen

I wylio golau cyntaf blaen y wawr,

Amynedd ennyd fer swn ochneidiau,

Arhoswch, a meddiennwch eich eneidiau."There is a great purpose

Behind what we see – restoration of joy

To watch the first light of dawn,

Patience a short while the sound of sighs,

Stay, and take possession of your souls.Every man, on release from prison, was greeted by huge crowds at the railway station and mass processions led by brass bands accompanied them round the streets of their native villages when they came home – Ammanford, Tumble, Cross Hands, Gwaun Cae Gurwen, Garnant. There were even concerts put on to welcome them back. As late as March 13th 1926, six months after the strike was over, a mass rally at the Albert Hall in London awarded medals to some of the recently-freed strikers. And later still, on April 3rd 1926 a mass rally in the Ivorites Hall in Ammanford drew charabancs from all over the valley.

Release of Anthracite Strikers 1925

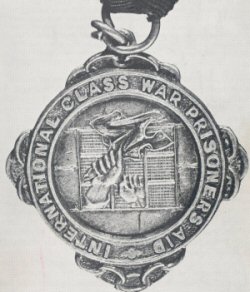

Each prisoner on his release was awarded a medal and a scroll by the International Class War Prisoners Aid Association.

Medal from the International Class War Prisoners' Aid Association, awarded to miners imprisoned in the 1925 anthracite strike. Yet these men who were imprisoned were not an unruly younger generation, lacking respect for law and order. Most were regular chapel-goers even if, as Garnant miner Glyn Evans remembered in 1973, some young miners in Garnant attended chapel only if it was raining and then only to run a sweepstake on the first hymn!

Many were older even than their union leaders, a notoriously geriatric crew, and were widely respected members of the community. One man jailed, Dai Dan Davies of Gwaun Cae Gurwen, was aged 50, had been a miner for 40 of those years, was a Glamorgan County Alderman and a University Court Governor for Swansea and Cardiff Universities. Morgan Morgan was 40 and the conductor of one of the brass bands which marched to Crynant. Evan Llewelyn of Ammanford who received 17 months was aged 50. Ianto Evans later became chairman of Ammanford Rural District Council. The character reference given for Edgar Lewis of Cross Hands was written by none other than one Owen Hughes, an elder of the Cross Hands Gospel Hall! (The police had claimed to be "terrified" by the Welsh hymn Aberystwyth which was sung by a crowd of men, led by Edgar Lewis, at Cross Hands colliery. The character reference did not, however, prevent Lewis from being jailed.). During the dispute the strike was co-ordinated by a Workers' Combine, or strike committee. The chairman, John Bevan, was a Justice of the Peace (ie a magistrate), while the vice chair, one D B Lewis, was a county councillor.

The average age of those arrested at the Ammanford No 2 disturbance on Pontamman bridge was 31; at the Pantyffynnon colliery disturbance the average age of those arrested was 39.

So what motivated men like these to strike and take part in major confrontation with the forces of the state? No-one takes the decision to strike lightly, despite what government and media propaganda would have us believe. It was difficult enough to live on a miner's wages in those days – it was impossible to live on nothing. It must have been something important at stake that forced men to take such drastic action as to strike with no guarantee of victory.

The last major dispute in the Anthracite District had been at Tumble thirty years previously. So what were the passions and, more importantly, the reasons for this mighty confrontation? The threat to the seniority rule was the flashpoint certainly, but there were other forces at work too. A detailed reading of the Llanelli Labour News throughout 1925 gives us some more clues. This was the paper of the Llanelli Labour Party and it covered the dispute in great detail, from the very beginnings right through to the trials of the arrested. At one stage during the dispute it gave full details of the shareholders of the two combines, and their share capital and dividends were conveniently broken down into their weekly profit so that miners could compare their pittances with the shareholders' profits.

Needless to say this caused much outrage from those shareholders listed, many of whom were local 'pillars of the community' such as vicars and local businessmen. Just why they should have been outraged by the publication of accounts and share dividends which were in the public domain, and which had to be published according to company law, only they can know. Guilt, perhaps. Or is guilt too human an emotion to attribute to a class of people notoriously born without such misgivings?

Sir Alfred Mond, the Chairman and major shareholder of the Amalgamated Combine, held £94,000 worth of shares (£4.28 million in 2008) which were yielding him a dividend of £168 a week. In addition he received an annual salary "in four figures". This, at a time when 300,000 miners were earning less than £2 a week. Translated into today's wages, Sir Alfred Mond's weekly dividend of 80 times a miner's weekly wage would be £7,658 a WEEK in 2008 – over a million pounds a year. And that was without his 'four figure' salary (£1,000 in 1925 was worth almost £500,000 at 2008 rates). Alfred Mond was also in the process of building the giant chemical conglomerate ICI that was to become the largest chemical company in the world.

No wonder these Ammanford men struck. Before Mond arrived on the scene life was difficult enough. But now precious holidays had been lost and Will Wilson had been sacked for upholding a custom of many years. And if they were allowed to sack one then they would surely sack many more.

The Aftermath – 1926

History, if it is not a guide and mentor to future generations, is nothing but an empty accumulation of dates and battles, a trivial catalogue of governments, prime ministers, kings and queens. Following hot on the heels of the 1925 dispute in the anthracite area, came the General Strike of May 1926 and it started for the same reasons as the anthracite strike. The fall in the price and demand of coal internationally had to be paid for somehow, and the Conservative government and the mine owners were determined that miners and their families paid for it.In the view of many historians, the 1926 General Strike was lost because the government and employers learnt valuable lessons from 1925 which the TUC leadership willfully forgot. The deep wage cuts, increased working hours and mass sackings that accompanied the defeat were the price of this amnesia. In 1925 the mine barons of the western valleys backed off in the face of an organised and determined rank-and-file action from the anthracite miners. The TUC's handling of the general strike did not go without criticism at the time nor has it since. It has to be said that much of the criticism of the TUC has come from political organization of the left hostile to the Communist Party as well as the 'reformist' politics of the TUC. There are some who have called the leadership disastrous and have accused the TUC of cowardly capitulation and even shameless collaboration with the Conservative government leading to the defeat of the General Strike. It is not the purpose to take sides here but it is necessary, in the interest of balance, at least to mention the unhappiness with the role of the TUC in 1926. Historians sympathetic to the TUC have written at length over the years defending the actions of the TUC General Council during the strike so it is proper and balanced to at least register some disagreement with these views.

And it has to be observed too, with the facts seeming to back it up, that the TUC did not follow the lead of anthracite miners and adopt militant picketing. Nor could the TUC have claimed ignorance of remote Ammanford either because they launched a fund for the dependents of those jailed and an official deputation, consisting of TUC and Labour Party national officials, met the Home Secretary on Feb 9th 1926 to ask for clemency for the prisoners (they didn't get it).

The passivity of the nine days of the General Strike and subsequent seven-month lock-out may have sealed the miners' doom. The rank and file miners were in charge of the 1925 Ammanford strike and its tactics. They stood to lose greatly if the mine owners succeeded in their attacks on living standards. The full-time, highly paid union officials who led the General Strike had no comparable interest and therefore no comparable incentive to fight.

The government seemed to have learned from events such as those that took place in Ammanford in 1925 because they worked closely with the TUC in order to keep the tactics adopted and the direction that the General Strike took firmly in the hands of the union leaders and well away from the rank and file.

During 1925 in Ammanford too, some full time union officials were critical of the strikers. But they were not allowed to get away with it – John Thomas, a miner's agent, was even compelled to resign because of his criticism. But the unique development of the anthracite district had ensured that the union leadership was not allowed to become divorced from their membership.

Dai Dan Evans was an anthracite miner in the inter-war years who later became general secretary of the south Wales NUM. Here's how he describes the difference between the anthracite area and the steam coal producing valleys further east -

"The difference between the leader and the ordinary rank and filer in the Anthracite area is much less than in the steam coal .... In the anthracite area, if you wanted to dismiss a man who was a bit of a 'trouble maker', they would have to take possibly a hundred men out before him (because of the seniority rule) .... Consequently, you see, you had lambs roaring like lions in the anthracite, and they had to bloody well be a lion to roar like a lion in the steam coalfield".

There are some modern day critics who might well have added that in the TUC they were lambs bleating like lambs.

The TUC instructed print unions not to print anything other than official TUC literature for the nine days of the General Strike. Even the Daily Herald, the only mass daily paper that supported the Labour Party and trade unions, was not allowed to publish. Yet newspapers such as the Daily Chronicle, which were pro-government, were printed. And the recently created BBC Wireless Service, then an arm of government, was giving out regular pro-government information and disinformation.

So the rank and file were prevented from printing or distributing any information of their own. Starved of information, fed only with odd scraps of government disinformation and limited TUC information thrown their way, confusion reigned as morale and will yielded to its rule. An old, tried and proven tactic, guaranteed to prevent action, succeeded beyond the wildest dreams of its instigators.

The only newspaper allowed to publish was the British Worker, the newspaper of the fledgling Communist Party, but every edition printed was vetted by the TUC. Line by line the paper was closely scrutinized, and scoured of any offending material before it was allowed to go to press.

Yet it was all so different just a year before when for ten days the strike was under the control of the strike committee. In the midst of all the turmoil and the troubles, in the face of great financial hardship and a hostile judiciary, the steadfastness of the anthracite miners secured the seniority rule. This achievement alone was sufficient to insulate the whole of the anthracite district from the open attack that took place on the mining unions elsewhere. Proof of this thesis can be found in the aftermath of the General Strike where, due to the seniority rule, victimization of militants by the coal owners after the return to work in November 1926 was made virtually impossible in the anthracite district.

Throughout the eastern valleys of Wales however, and indeed the rest of the British coalfields, where they did not have this important self defence weapon, the retribution was terrible. The coal owners literally picked and chose whom they took back on. In fact, many victimized Rhondda miners, including Arthur Horner, the future president of the Miners Federation of Great Britain, came to our Anthracite District when they were completely black listed in the Rhondda.

The deprivations of the thirties are well known and well documented. It took a whole generation and another World War before times got better for working people. Few are now left who remember those days, a few more can remember their parents talking about them, but most people of Ammanford and elsewhere are wholly unaware of their history. We can make little sense of the present at the best of times; we will make none at all without the past to explain it for us.

Note:

The authoritive account of this dispute (from which much of the above has been taken) was written by Hywel Francis and published in Llafur (Labour) in 1973. Click HERE for the full text of this articleSources:

Jim Griffiths: Pages from Memory (1969)

Llanelli Labour News (1925-1926)

Hywel Francis (1973): "The Anthracite Strike and Disturbances of 1925", Llafur I.2 (Journal for the Society for the study of Welsh Labour history).

Date this page last updated: August 24, 2010