CONTENTS

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 School, sadly, has taught many of us to identify history with the boredom of the class room and its interminable dates, battles, generals, kings, politicians and potentates. But it needn't be so, and events we still remember can provide another kind of history, one which can often make the subject come alive in a way that our teachers couldn't.

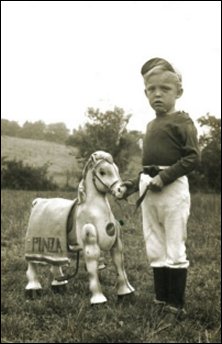

Coronation carnival of 1953, Myddynfych council estate. The author, aged 6, is dressed up as the Queen's jockey, Gordon Richards, who had just won his only Derby after 30 years of trying, appropriately enough in the Coronation year. The winning horse, Pinza, is at my side. The exertions of the Derby's mile and a half course appear to have caused Pinza a dramatic weight loss. The carnivals once held in Ammanford fall into that category. Their rise – and fall – are an example of social history in the making and while they may have seemed like harmless entertainment at the time they were, in fact, a product of the social forces of their day.

The first all-Ammanford carnivals were held on the coronation of the current queen in 1953 – the forerunners of the modern street parties. But they were quite different matters back in 1953. Each of the newly built council housing estates held carnivals which involved extremely elaborate floats, or tableaux, built on backs of lorries, as well as individuals dressing up in costume. This author can still remember the party afterwards that went on late into the night on Myddynfych council estate, the back of a lorry once again serving as a stage for the residents to do their party pieces. All without the benefit of microphones and amplification systems, which weren't available in those far-off days. And the singing was real then, too, as many of the residents of the housing estates were members of local choirs. No karaoke or discos or even record players.

But even before the coronation, carnivals were organised by Pullman's, a local factory, for their employees and their families. Pullman's was the largest single place of employment in the Ammanford area and employed about 1,100 people at one point after the war. The National Coal Board was the largest employer overall, but no single mine employed more than 800 people and most had considerably fewer. Pullman's Springfilled Company Ltd had been built in 1945 on a government-sponsored site that had been created in 1943 for war industries. The London-based company took over more land in 1947 and grew steadily throughout the 1950s until increasing competition for its spring-filled mattresses saw its market share decline throughout the 1960s, and it ceased trading in 1967. A new company, Delanair Ltd., manufacturing car heating units, took over the factory premises in 1969 only to bought up by French company Valeo Climate Control Ltd, who transferred to a new factory in Gorseinon, near Swansea, in 1992. Valeo themselves went into receivership in 2002.

Very soon, the baton of carnival organsation was taken up by the newly built council housing estates, which had been constructed in the years immediately after the war. Most of those who moved into the houses were working class families, with about half the adult male residents employed in local mines. The rest worked in local factories, on the railways, on the buildings, or they were tradesmen such as carpenters, fitters, electricians, plasterers and plumbers. As a result, they were in possession of the very skills that were needed to build the often extremely elaborate floats that soon became the focus of their attention. Every householder also possessed some DIY skills – and out of necessity, not as a hobby or a lifestyle statement as all so often seems the case today. Wages, while considerable better than the pre-war levels, were still very low and so it was crucial that you had to look after your own home repairs, painting and decorating.

Car ownership was rare too and so, during the two weeks in August when all the mines and factories closed down (the colliers' fortnight), families stayed in Ammanford. What holidays there were consisted of day trips by coach to the seaside – charabanc outings – but very few people went off for longer than a day's excursion: they simply couldn't afford to.

As a result, the carnivals became the focus for their energies, released, if only for a a few weeks, from the shackles of the mine or factory. And what energies were released too. Preparation for the carnival started long before the event itself. As the summer evenings lengthened the hammering and sawing of the men could be heard in back gardens and sheds while the women's sewing and cutting was no less energetic for being less noisy. Materials were found, begged or borrowed, and considerable imagination and improvisation had to be employed. There was no MFI or B&Q, even if people could have afforded their products.

When my father built the Bridge on the River Kwai float in 1958 (still talked about today, believe it or not) quite a few trips to the local woods were required to find the material (see the photo below). This float was typical of the time; the film of that name starring Alec Guiness had just been showing in local cinemas and this was where the idea came from. The film depicts the war-time construction (1942-43) of a section of the Burma railway passing over the river Kwai which the Japanese had built using forced labour, including prisoners of war. The conditions on the 415 kilometres of railway were brutal in the extreme, and 100,000 of the 250,000 native slave force, plus 13,000 of the 60,000 Allied prisoners of war, died during the railway's construction (that's one death for every 4 metres of track built). What gave this tableau added poignancy, even authenticity, was that my father (bottom right in the photo) had himself been a prisoner of war for three years after being captured with his regiment in Tobruk, North Africa, in June 1942, spending the rest of the war in Italian and German prison camps. Amongst Ammanford's numerous ex-servicemen at that time were several who survived the Burma railway itself. And some of the khaki uniforms worn in the photograph were real ones, brought home by servicemen on their demobilisation.

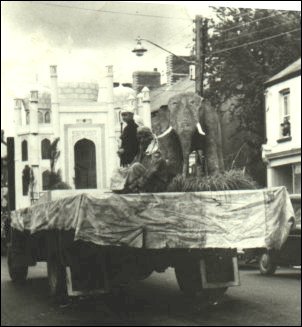

My father used to decide about Easter time what that year's float would be, and once, when the construction required large volumes of papier maché (see The Building of the Sphinx in the 'Photograph' section of this website), our newspapers, along with those of our neighbours, were stockpiled in our shed until there was enough for the job. The theme of each float was often a recent film or show but no excuse was really needed. One year my father's float was the 'Taj Mahal' and not only did the lorry carry a mock-up of the building itself through the streets of Ammanford but a life-sized papier maché elephant stared out at the watching crowd. (see photo below).

All the Ammanford and Betws housing estates took part – Myddynfych in Tirydail, Carregamman and Iscennen in Ammanford, Parcyrhun in Pantyffynnon, and Caemawr and Treforis in Betws. Each housing estate formed a committee months before the carnival was due to start and regular meetings and monitoring of progress took place. Each housing estate then elected a delegate to the main organising committee, democratic practices learnt in their local trade unions. Competition was intense – spies were even sent out to peep over garden fences and hedges to see what the opposition in other estates was up to.

Soon the carnivals had become well organised with the first cup being awarded to the winning estate in 1958. The carnival itself took the form of a mass parade round the town on August Bank Holiday during the collier's fortnight. Hundreds of people took part and thousands more lined the streets as the procession snaked its way along the main streets of the town. The procession eventually arrived at the local recreation ground – the Rec – where the prizes were awarded. The entire recreation ground was covered with floats, participants and spectators. Prizes were awarded to best float by category, best float overall, as well as numerous individual categories, male and female, adult and children. Each housing estate was led in the parade by their jazz band which rehearsed for months before and was also entered for the best jazz band prize. At the end of the judging on the day, all the points were added up and the top accolade of all went to the winning estate which was awarded a cup as prize.

Myddynfych carnival committee chairman Gwynfor Bevan (left) receiving the first cup for the winning estate in 1958 The local newspaper at the time, 'The Amman Valley Chronicle and East Carmarthen News', described the 1958 carnival as "the best yet." It reported that 5,000 spectators watched 40 floats (or tableaux) form a procession three quarters of a mile long before everyone congregated at the Recreation ground – and this was on a day when it rained heavily. Myddynfych won the first cup awarded to the best council estate. The "Bridge on the River Kwai", also from Myddynfych, won the cup for the best adult tableau and the best children's tableau was won by "Tulips from Amsterdam" from Parcyrhun estate. Myddynfych produced the best youth jazz band (these and other photographs can be found in the 'Photographs' section of this website).

The photographs on your computer screen can only give the faintest idea of the quality of some of these floats. The black and white pictures of the era also do no justice at all to the incredible colour of the occasion. And the sheer number of the entries and spectators can only be recalled by those who were there.

The era of the carnival was rather brief, however. Their heyday was from about 1950 to the late sixties, after when the motor car and the cheap package holiday were becoming more affordable. People no longer stayed home for their fortnight holiday and gradually fewer and fewer floats were built and their overall quality fell. Eventually the carnivals ceased completely though they have been revived in recent years at a much reduced scale. As the social conditions that created the carnivals changed, newer forms of entertainment replaced them, which needed less and less participation from people themselves. The lorries that carried the floats were loaned free by local businesses and farmers and not a few were coal lorries which required cleaning before use! But by the 2000s, the premiums the insurance companies now demand for accident cover have reached such exorbitant levels that no-one will loan a lorry anymore.

Still, for those of us who took part in them, the carnivals were amongst the highlights of our childhood and even our parents looked back on them as days in a golden age. Their generation, after all, had known only the poverty and deprivation of the inter-war years followed by the horrors and losses of the war itself. For the first time in history people had good quality housing, full employment, reasonable wages, a free education system for their children, a National Health Service for all, free at the point of use to provide for them in their old age and – most important of all – hope in the future for their children. Where's that all gone now, Tony Blair?

Note: The carnival photographs in this section are all of Myddynfych estate and are from my personal collection. Every other estate produced tableaux of comparable merit. Photos of some of the carnival floats can be seen in the 'Photographs' section of this website.

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 2. AMMANFORD'S COUNCIL HOUSING ESTATES

As we've just seen, the carnivals in Ammanford couldn't have happened without the council housing estates, each of which deserves a brief history of its own. And the creation of social housing can't be fully understood without an introduction to the post-war political situation.

On the 7th May l945 Germany surrendered to the Allied Forces and 8th May was declared V-E day (Victory in Europe). The war against Japan was still raging in the Far East though and would continue until Japan's surrender after American atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima on 6th August and Nagasaki on the 9th August. But even with the war in Japan still in progress, a General Election was called as a signal that normal service was being resumed. The British wartime parliament met for the last time on 15 June 1945, dissolved itself, and polling day was scheduled for 5 July with a delay in the announcement of results for three weeks, so that a service vote of Britain's armed forces, still on active duty all over the world, could be collected.

War had been declared on 3rd September 1939, and from May 1940 the British government became a coalition of all political parties, who chose the Conservative Winston Churchill as Prime Minister on 10th May 1940. But now, with the war won, domestic politics reverted to normal, and the election was conducted along the usual party political lines.

Politics in peacetime

The Labour Party's landslide in this general election remains one of the greatest shocks in British political history. The result, declared on 26th July 1945, couldn't have been more clear-cut – Labour won 393 parliamentary seats with the Conservatives almost 200 behind on 197. The other six political parties returned only 33 seats between them, with the Liberals being the largest of the also-rans with just 12 seats! [see: http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/GE1945.htm]How did Winston Churchill, a hugely popular national hero, fail to win? Between 1940 and 1945 Winston Churchill was probably the most popular British prime minister of all time. In May 1945 his approval rating in the opinion polls, which had never fallen below 78 per cent, stood at 83 per cent. With few exceptions, politicians and commentators confidently predicted that he would lead the Conservatives to victory at the forthcoming general election

In the event, the man who had just 'won' the war for the country (with a little help from his armed forces and the other Allies, of course) led them to one of their greatest ever electoral defeats. It was also one for which he was partly responsible, because the very qualities that had made him a great leader in war were ill-suited to domestic politics in peacetime. An election broadcast he made in May 1945 may give a clue to why he was rejected:

"I must tell you that a socialist policy is abhorrent to British ideas on freedom. There is to be one State, to which all are to be obedient in every act of their lives. This State, once in power, will prescribe for everyone: where they are to work, what they are to work at, where they may go and what they may say, what views they are to hold, where their wives are to queue up for the State ration, and what education their children are to receive. A socialist state could not afford to suffer opposition – no socialist system can be established without a political police. They (the Labour government) would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo." (http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/ww2/A1057457)

This was a ridiculous exaggeration, and a libel on the moderate post-war Labour Party, especially the comparison of Labour to the Gestapo, of which millions of returning servicemen had just had close experience. Those who had borne the worse of the fighting had been the British working class, and to compare the Labour Party, which they overwhelmingly supported, to the Gestapo was as stupid as it was insulting. The British electorate not only knew this, but acted on it in the July elections.

Amongst the numerous radical policies introduced by Labour Prime Minister Clement Atlee and his newly elected government was the nationalisation of Britain's key industries, the so-called infrastructure industries of coal, iron and steel, electricity, gas, water, civil aviation, telecommunications, most road haulage, and railways. This wasn't an ideological act, as many still believe today, but an essential step to revive British industry which had been ruinously depleted during the war years – even after the Tories' won the 1951 General Election, the only industry they re-privatised was iron and steel in 1954, leaving everything else nationalised. The scale of industry's exhaustion was so great after the war that only intervention at governmental level was capable of rebuilding it to its pre-war level (and using tax-payers' money to compensate the owners). As a leading political commentator has written: "From the beginning, the nationalisation proposals of the government were designed to achieve the sole purpose of improving the efficiency of the capitalist economy, not as marking the beginning of its wholesale transformation." (Ralph Miliband, Parliamentary Socialism: A Study in the Politics of Labour; London: Merlin Press, 1973.)On the social side, Labour inaugurated the modern Welfare State, whose provisions included nationalising the health services, with doctors and hospital provision now available free at the point of use. Education, too, was brought under state control, with nursery, infants, primary and secondary education finally provided at no direct cost to the pupils or their parents. University education also became free, with the added bonus of grants to ensure that children from low income families could survive once they'd won themselves a university place (remember those days?). One of those pupils who benefited from free university education was Tony Blair, the Labour Prime Minister from 1997 to 2007, whose government when elected in 1997 promptly scrapped all the grants and fee exemptions that he and most of his Members of Parliament had themselves enjoyed.

But at local council level, another, quieter revolution was under way: the creation of social housing, made possible by new planning laws and extra cash from the newly elected national government. This was most needed in the cities and larger towns where literally tens of thousands of homes had been bombed to oblivion during the German air raids of the Blitz. Up and down the country, newly-built council housing estates were rapidly appearing, with the aim of providing cheap rented accommodation for local people, including returning soldiers and their families. The Labour government had certainly read up on their history, for it was the failure of national governments to address these major social and economic problems after the First World War that had contributed to the awful economic depression of the 1930s, and whose political consequences were the rise of Fascism and Nazism throughout Europe. The Second World War was well and truly born out of the mistakes of the First.

Even the USA, citadel of free-enterprise capitalism, introduced a watered-down version of state-funded assistance after the war through its 'G.I. bill' (officially called the 'Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944'), which provided many benefits to veterans of World War II. It established veterans' hospitals, provided for vocational rehabilitation, made low-interest mortgages available, and granted stipends covering tuition and living expenses for veterans attending college or trade schools. Subsequent legislation extended these benefits to veterans of the Korean War, and the Readjustment Benefits Act of 1966 extended them to all who served in the armed forces even in peacetime. From 1944 to 1949, nearly 9 million veterans received close to $4 billion from the GI bill's unemployment compensation program. The education and training provisions existed until 1956, providing benefits to nearly 10 million veterans. The Veterans' Administration offered insured loans until 1962, and they totalled more than $50 billion. The economic assistance provided by the GI bill and the Veterans' Administration accelerated the postwar demand for goods and services. This was the closest the USA has ever been, before or since, to the British Welfare State.

[http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_036500_gibill.htm]

The motives for nationalising the British health services, and semi-nationalising housing, were pragmatic as well as ideologically motivated: the reconstruction of British industry after the devastation of war required a healthy and fit work force, while the new technological society that was slowly emerging required this work force to be literate, numerate and educated as well.

In this fever of house building Ammanford was to be no different from the rest of the country and all our present council estates except one are the creation of these postwar years. Rural council estates have a different history to their urban counterparts, where shortage of land meant that existing dwellings (usually slum terraces) were demolished to make way for the new. The popular image of council estates as high-rise blocks of flats, or sprawling, charmless sites with landings opening onto bleak urban vistas, may be true in the inner cities, but not in the countryside, and certainly not in the Amman Valley.

There was no shortage of land among Carmarthenshire's rich farming acres, and the postwar council estates in the Amman Valley were built on green fields. Most of the ones in Ammanford were in fact named after the farms on whose meadows they were built. None of these farms exist any more except for Myddynfych, whose current owners no longer farm their fields, and the farmhouse is now in use solely as a dwelling.

All the estates are still here today, though most of the houses have been sold into private ownership under the 'Right to Buy' scheme of recent governments. Perhaps only a quarter of homes on the estates today are still owned by the local authority. They were – and are – all high standard housing, for all the 'council house' tag attached to them. Most homes are three-bedroom, semi-detached buildings with front lawns and back gardens, though a few smaller flats were also built for the elderly. This is one of the reasons why a house in Myddynfych sold for just under £100,000 in 2004. A former council house in Mumbles, just outside Swansea, sold for £250,000 at the same time. Mumbles is where Hollywood actress Catherine Zeta Jones has built her million pound pied-à-terre so even former council houses have become very desirable indeed. In time, the entire stock of our housing estates will find its way into private ownership. A great shame, because the idea behind their creation was to provide cheap rented housing to young families who couldn't afford to buy. If their financial circumstances took an upturn later, and they were able to purchase their own homes, or they moved out of the area, then their house became available for others.

There was a sort of hereditary element, too, in that a son or daughter of a council house tenant had first option to rent if their parents gave up their tenancy. Without this scheme, my parents certainly couldn't have afforded the standard of housing in Myddynfych in which I grew up and it's a tragedy that young families today can't either.

Another important factor in this type of housing was that you had, if you so chose, a home for life. Parents could now make long-term plans for themselves and their children, impossible with the uncertainties of pre-war housing conditions. But today, the reduction of council house building since the 1980s has been compounded by a systematic weakening of rent protection legislation in the private sector so that, once more, private tenants find themselves prey to short-term leases offering no long-term security at all.

In chronological order of their construction, here are the housing estates in Ammanford, with English translations of their names.

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 1921 – Iscennen Road (Below the Cennen)

This cross-shaped estate of about seventy houses is a product of the years immediately after the First World War, not the Second one, and repesents Ammanford's first attempt at social housing. Ammanford Urban District Council had been created in 1903 in recognition that Ammanford, not the much older parishes of Betws and Llandybie, was now the dominant town in the Amman Valley thanks to the patronage of 'King Coal'. This estate of semi-detached houses was the first municipal housing project undertaken by Ammanford UDC. The were often referrred to as the 1919 houses, after the Local Government Act of that year which enabled the local council to finance the scheme. In March 1920 the council commissioned a local architect, Mr David Thomas, to prepare the scheme. Tenders were invited and presented to the council in October 1920, so that work commenced at the end of that year and the estate was completed in 1921.

....The estate stands on a field originally owned by the 6th Lord Dynevor, Arthur De Cardonel Rice, (24th Jan 1836 to 16th Dec 1889). W. T. H. Locksmith in his book on Ammanford street names conjectures that it was he who probably gave the original street its name, after a 15th century ancestor, Gruffydd ap Nicholas, Lord Is-Cennen. (The Dynevor family once owned most of the land in the Amman valley. See 'The Dynevor Peerage: a History' in the 'History' section of this webssite or click HERE.)

....The name Iscennen takes its name from the medieval Commote of Iskennen, roughly equal in extent to the area between the Towy and Amman rivers. Is-Cennen comes from "Is" = lower and 'Cennen', the river flowing into the Towy at Llandeilo; therefore the name means 'below Cennen', (ie south of Llandeilo). The administrative – and militiary – centre was the impregnable Carreg Cennen Castle, built on a limestone outcrop three hundred feet above the river Cennen. A Commote was a division of land for administrative purposes. There were 50 trefydd (towns) in each commote, and two or three Commotes normally made up a Cantref ('cant' = a hundred and 'tref' = town). A Cantref is approximately equivalent to a modern Borough. The Commote was further divided into twelve manors of four trefi each, making 48 trefydd in all and with the two extra trefydd or towns being the property of the king. Many modern parishes have roughly the same boundaries as these medieval manors, including today's Parish of Llandybie, which is still a pretty good fit for the thousand-year old Manor of Myddynfych. The modern Welsh word 'tref' is usually translated as 'town' but towns in the Middle Ages were far smaller affairs than their modern counterparts, and were basically small settlements of a few homesteads and farms. Two, or sometimes three Cantrefs usually made up the equivalent of a modern Shire County.

....The Amman Valley is situated in the Commote of Iskennen of the Cantref Bychan. Had there been postal addresses in those days Ammanford would probably have read something like this: Manor of Myddynfych, (Parish of Llandybie), Commote of Iskennen (Borough of Dinewfr), Cantref Bychan (Carmartheshire), Kingdom of Deheubarth (Dyfed).

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 1947 – Caemawr (the big field)

An estate in Betws, with about 50 houses built to a T-shaped plan. This was the first estate to have been built by Ammanford Urban District Council after World War Two, despite major problems in obtaining building materials in short supply due to the massive postwar rebuilding programme. The 1875 Ordnance Survey map was the first map for this area to be drawn to a 1/25,000 scale, which enabled individual fields to be shown for the first time. On the Carmarthenshire Ordnance Sheet 48/12, Caemawr is marked as field number 1004, having an area of 6.067 acres, the first time it had appeared on any map.

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 1948 – Carregamman (stone of the Amman)

With 50 pre-fabricated homes arranged in a U-shape, this was the next estate built in Ammanford, on land first purchased in 1946. The postwar shortage of building materials proved insurmountable this time, with the result that prefabricated homes were constructed instead, brick-built only for the first floor and corrugated sheets used for the upstairs section of the houses. Originally intended as a short-term solution, these buildings, designed to a BISF (British Iron and Steel Federation) specification, remained in their original 'pre-fab' state until 1995 when they were demolished and completely rebuilt in more traditional brick.

....The name Carregamman comes from one of the oldest farmsteads in the area, presumably built from stone taken from the adjoining Amman river. (In 1885 a new church, St Michael's, was built in Ammanford which also used stone from the river.) There had originally been three farms, named Carregamman Uchaf, Carregamman Ganol and Carregamman Isaf (upper, middle and lower Carregamman respectively).

....But on the 1875 Ordnance Map a new farmstead called simply Carregamman appeared next to Quay Street, equidistant between the two older farms. The larger of the original two farms was Carregamman Uchaf on what is now High Street, and on the same 1875 Ordnance map it has been renamed Bettws Vicarage, after its sale and conversion for ecclesiastical use sometime before this. Completed in 1804, it was purchased by the Bishop of St David's in 1835 and seems to have become a vicarage from then on. The Great Western Railway Company went past these two buildings and Carregamman Isaf was eventually bought by them to become a railway lodge named Bedwelty.

....In a book, Historic Carmarthenshire Homes and their Families, written by Francis Jones in 1986, there is an entry for Carreg Aman:"Half a mile south of Cross Inn (now Ammanford). In 1779 (and earlier) Carreg Aman Uchaf (7 acres) and -isaf (44 acres) formed part of the Dynevor estate. Later these properties were sold to the Jones family who built up the Carreg Aman estate. The family's ancestor David John ap William Edward (vivens 1792) owned some small properties in the hills north of Ammanford, and once attended a sale of Carreg Aman, where the auctioneer was clearly partial to some local bidders. Noting that the unknown hill-farmer was resolutely leading 'the field', the auctioneer stopped, am addressed the stranger - 'I do not know you. Have you any sureties that you will be able to pay?' 'Yes' was the reply, and holding up a large bag full of golden sovereigns, 'these are my sureties'. His son John Jones succeed him, and the family continued to increase their estate. One of the last of the family was my old friend, Major Godfrey Morgan Morris, T.D., D.L. While serving in North Italy during World War II, he was severely wounded and captured by the Germans. His parents had no news whatsoever of him for over nine months. While anxiously waiting, a touching event occurred. Throughout active service he had carried with him his Welsh Bible, which was afterwards found on the battlefield by a young officer from Glamorgan who later brought it home and handed it to an aquaintance who travelled to Ammanford and returned it to the anxious parents. Major Morgan-Morris was an only son, and after his death in 1970 at the age of 56, the Carreg Aman estate passed to his first-cousin, Mrs Marcia Rowlands."

....The estate mentioned by Francis Jones no longer includes the farmlands of Carreg Aman, now a housing estate, but much of the land and property in the town of Ammanford itself is still owned by the Carreg Aman Estate. The old manor house becme a ruin and was demolished in the 1950s.

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 1949-1951 – Myddynfych (the little army?)

Myddynfych is the largest of Ammanford's estates with about 200 houses and flats, and was built to a circular plan with two short streets fitting neatly inside. In fact it consists of four streets – Myddynfych, Arthur Street, Heol Marlais and Heol-y-Wyrddol. Two more streets named Heol Llwyd and Riverway were added in 1973-74 which created fifty more flats and houses. Surrounded by fields, woods and streams, this was an idyllic environment in which to grow up. The estate is named after the nearby farmstead, Myddynfych Farm, which can be dated to the ninth century AD. (See a separate item in the 'History' section of this website entitled 'Myddynfych: the oldest building in Ammanford', or click HERE.)

....In the late 1890s the farm and its land were bought up by local property developer Mr Henry Herbert of Brynmarlais, Bonllwyn. Henry Herbert had also sunk the first commercial-scale coal mines in the area in 1890, what were to become Ammanford Nos 1 and 2 collieries. In 1949 his family sold the field adjoining Llandybie Road at Tirydail Square to the local council, and the modern housing estate of Myddynfych was built. The farm however, appears to be steadily deteriorating under its current ownership. Myddynfych farm is still occupied to this day, though in a much sorrier condition than even twenty years ago. Even though it is now a listed building there is concern that such a historic farmhouse may not survive its recent years of neglect for much longer. In an age when most buildings are lucky enough to see 100 years, so keen are the property developers and their bulldozers to get to work, it would be a shame to see anything happen to a such a venerable survivor as Myddynfych farm.

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 1950s – Treforis (Morris town)

Treforis is built in a straight line of about 50 houses in Betws and named after a local dignitary called Colonel Morris. After a career in the Indian Army, David Morris, born in 1843 in Coedcaebach, Betws, returned home bearing the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Despite little education, he had gone to the Indian Army as a railway engineer with experience gained on the Swansea to Brecon railway. In India he had been responsible for the planning of one of the first railways to have been built in the sub-continent. He next became involved in mining ore in the Punjab and was one of the officers put in charge of the port of Karachi before returning to his native Betws in 1899. On his return he soon assumed the role of a country gentleman, building a large house, Brynffin, as his residence, becoming a Justice of the Peace, a local councillor, a governor of Aberystwyth University and an active member of Capel Newydd, the recently rebuilt Welsh Methodist Chapel on Betws Road. After his death in 1913 the road he had lived on was named Colonel Road in his memory.

....Colonel Morris was sufficiently important to be mentioned by name, along with Ammanford's major landowners, in the 1910 edition of 'Kelly's Directory for South Wales':Brynffin, is the property and residence of Lieut.-Col. David Morris. The Hon. W. F. Rice [ie the 7th Baron Dynevor, Walter Fitz Uryan Rice], Mrs. Jones of Carregamman, and W. N. Jones esq. J.P. are the principal landowners.

His house, Brynffin, later became the residence of the parents of Ivor Richard, later to become Baron Richard of Ammanford, (see essay in the "People" section of this website).

....Treforis is unique among the Ammanford and Betws council estates in that it was built, not by Ammanford Urban District Council but by Llandeilo Rural District Council. By some anomaly of local government map-making Treforis, nine miles south of Llandeilo, had been included within its boundaries, while Caemawr, just half a mile north, was in Ammanford. A glance at the map will show how strange this looks.

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 1956 – Parcyrhun (Rhun's field)

The hundred or so houses of Parcyrhun are built to a triangular plan. Rhun is a man's Christian name, common in the Middle Ages and still in use today.According to a legend, Rhun was one of a hundred children fathered by the Welsh Prince Brychan Brycheiniog, who ruled much of South Wales in the fifth century AD. If the Rhun of Parcyrhun was a real person, then he would almost certainly have lived much later than this period. One of Rhun's sisters was St Tybie, after whom Llandybie is named (see the item on Llandybie Church in the 'Churches and Chapels section of this website).

The manor and estate of Parcyrhun was situated in the medieval commote (Lordship) of Iscennen (Iscennen means below the Cennen). Iscennen consisted of all the lands between the river Towy and the Amman, a large and fertile area of prime farming land and therefore the source of considerable wealth. When the English King Edward I finally subdued Wales in 1284 all lands, including the Lordship of Iscennen, passed into the ownership of the English crown, and for a couple of centuries after this it was rented out to various supporters loyal to the King.

After 1485 the Lordship of Iscennen was given to a local Llandeilo magnate, Rhys ap Thomas, by King Henry VII. Rhys had raised an army in support of Henry when he defeated Richad III at the battle of Bosworth in 1485, becoming King in the process. The Lordship of Iscennen was given to Rhys ap Thomas as his reward. The poet Lewys Glyn Cothi (died around 1486) wrote an ode of praise to Hywel ap Henri ap Gwilym ap Thomas Fychan 'O Barc y Rhun', whom he called 'prince of Iscennen'.

In later years Parcyrhun became a farm and manor house. It is shown on Sexton's map of Carmarthenshire, published in 1578, as Parkreame, presumably an Englishman's attempt at Welsh orthography. In 1774 Park yr Hun-Uchaf (122 acres) and -Isaf (136 acres) were part of the Dynevor estate. The postwar local authority bought a field belonging to the farm and completed the housing estate in 1956. Then, in 1958, the council also acquired the manor house with its surrounding gardens, demolishing them in 1962.

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 1957 – Heol Wallasey (Wallasey Street)

This small estate consists of about 30 flats and houses extending in a straight line from Quay Street. Originally called Alexandra Road it became known as Heol Post (Post Street), presumably because the local postman, John Gould, lived here around 1897. It next became known as Field Street, as it led to an enclosure on which many local events were held (on July 11th 1914, for example, the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds organised a show on the field). On 19th September 1957 the first sod was cut to start a new housing development on the street. The name given to the street is conspicuous in a town where most street names are either self-explanatory (Station Road, Church Street, High Street, New Road, Old Road, Park Street, etc.) or in Welsh.

....By 1928 Ammanford was still reeling from the seven month long lock-out that had followed the brief nine day General Strike of 1926. The reduction in wages that was the consequence of defeat cut deep, and the mining areas were hit hard compared to regions which had other industries to sustain them. The townspeople of Ammanford had already suffered a four month long strike that had crippled the West Wales Anthracite District during the Summer of 1925, and the pit closure programme following these two torrid disputes saw Tirydail and Ammanford No 1 collieries closed for good, so debt from the strike years was compounded by unemployment from the pit closures. As proof of what the depression in Ammanford was like at this time, we can draw on the accounts of Ammanford Co-operative Society for that period. In 1920, Ammanford's 1,700 members spent £176,941 with the Co-op. In 1930, even though the membership had grown to 1,930, the sales had plummeted to just £82,053 – less than half of what it was a decade before. And the 1920 reserves of £1,881 in the bank had shrunk dramatically to just £36 in 1930! The depths of the depression in that decade, with its accompanying poverty and distress, can be imagined in those figures alone. The financial credit that the Co-op extended to its members took years to pay back, with some individuals taking ten years to discharge their debt, but pay it back they did. [There's a separate item on Ammanford Co-operative Society in the 'History' section of this website, or click HERE.]

....In 1928 the Mayor of Wallasey, across the Mersey from Liverpool, had raised £1,200 for relief of distress in the district, along with fourteen tons of clothes, and in 1957 the new street was renamed Heol Wallasey in recognition of this generosity. One of the men who had led a delegation to Wallasey was Ammanford's Congregationalist Minister D. Tegfan Davies and he was given the honour of cutting the first sod in 1957. [There's a separate item on D. Tegfan Davies in the 'People' section of this website, or click HERE.]

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980 1980 – Gwynfryn (White Hill)

The last of Ammanford's council estates was built too late for the carnival era but it owes its significance to being the last gasp of the town's council house building programme. The Margaret Thatcher-led Conservative government elected in 1979 would soon introduce the 'Right to Buy' scheme allowing council tenants to buy their council houses outright (the same right wasn't, and still isn't, extended to privately rented accommodation). Worse, local councils weren't even allowed to use the money from house sales to replace them. Social housing from now on would be the prerogative of the Housing Associations created by the earlier Conservative government of 1970-1974, led by Edward Heath. Although these are 'non-profit' organisations they are also outside the control of democratically elected local councils.

.... Gwynfryn estate of about a hundred houses, flats and bungalows lies alongside the river Loughor in an area known as Tirydail (Land of the Leaves). The residents are a mixed demographic of young and old, the elderly residents living in a group of bungalows at the top corner of the estate. Across the road is Ammanford's Technical College which has a history all of its own [See 'Ammanford Technical College' in the Education part of the 'History' section or click HERE.] But the field on which Gwynfryn is built is a history lesson itself of how Ammanford changed from an agricultural economy to an industrial one, and how the older gentry families were replaced in political and economic dominance by a newer, industrial class.

....Lieutenant-Colonel William Nathaniel Jones, one of the founders of modern Ammanford, was one of the new breed of industrialists who were swiftly replacing the landed gentry in economic and political importance throughout the rural areas of Britain. Their wealth – and therefore power – came not from land and rent income but from manufacturing. Colonel W. N. Jones was one of several of Ammanford's grandees who made their name and fortune by developing industry in the area. He was a prominent local auctioneer and businessman and was briefly the Liberal MP for Carmarthenshire in 1928. In 1882 the Dyffryn Estate in Tirydail, near the railway station, was placed on the market at auction in ten lots and Colonel Jones bought lots 2, 3, 6, 7 and 8 on the east bank of the river Loughor, though not initially the mansion on the west bank that went with the land. The estate and its mansion dated back to the early 1700s and is believed to have belonged to the Powell family.

....Colonel Jones used the newly acquired land for heavy industrial development. He expanded his operations to build the Aberlash Tinplate Works on the Tirydail bank of the Loughor in 1889, along with Ammanford Gasworks. This heavy industry (and, one would guess, dirty and noisy industry as well), caused friction between Colonel Jones and the owners of Dyffryn Mansion the other side of the river Loughor, and a lengthy legal battle ensued. In settlement of the dispute Aberlash Tinplate Company bought out the owner of Dyffryn Mansion, with Colonel Jones himself taking up residence there in 1892.

....A story about his acquisition of Dyffryn Mansion has travelled down the years which, if true, is quite revealing. According to this tale, production at his Tinplate works (built well within hearing-distance of Dyffryn Mansion) was increased to 24 hours a day. The noise throughout the night may be easily imagined, but when Colonel Jones moved into the mansion himself in 1892, the former owners having been driven off, night-time production ceased immediately. All good stories deserve to be true, of course, and if this one is correct then today's property developers have no new tricks up their sleeves.

....Over the years the estate dwindled in size with various sales and developments. The house itself was eventually abandoned by the descendants of Colonel Jones and remained unoccupied for years. In time vandalism and the weather had combined to render it structurally unsound. It was demolished in 1977 and Gwynfryn replaced it in 1980. Gwynfryn means literally 'white hill' but it is also a Welsh Christian name and in this instance the estate is named after an Ammanford councillor, Gwynfryn Davies, BA, BSc., who had been leader of Dinefwr Borough Council. The estate consists of three streets – Station Road, Heol Haydn and Rhodfa Frank, the last two also being named after former Ammanford councillors, Haydn Lewis and Frank Davies.

....Colonel Jones also sold other land around the tinplate works for housing to be built for his workforce and that of Tirydail Colliery, just a few yards across the Loughor from his Tinplate works (this colliery closed in the aftermath of the 1926 General Strike). Three of the streets – Harold Street, Norman Road and Florence Road – bear the names of his children, presumably to gain for his family what the rich think is immortality (and the poor know is vanity).

OTHER ESTATES:

The above council estates were all within the boundaries of the old Ammanford Urban District Council (roughly bounded by the Amman and Loughor rivers) which had been created in 1903. But just outside Ammanford are other council estates, some of whom organised their own carnivals independent of Ammanford, and others which were too small for this level of activity. Along the banks of the river Amman there are estates at Glanamman, Garnant, Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen, and Brynamman. Nearby Llandybie village has its own estates as well as the smaller 20 houses of Maes Llwyn in Bonllwyn. There is an estate in Saron and nearby Maes y Dail, while there are also council-built estates in Capel Hendre and Tycroes. At the top of Maesquarre Road in Betws is another estate which marks the start of the Betws mountain. All of these were built during the same timeframe as Ammanford's.Sources: The history of the carnivals in Ammanford has been drawn from personal memories and photographs. For the history of the council estates themselves, use has been made of AMMANFORD: Origin of Street Names & Notable Historical Records by W T H Locksmith, published in 1999 by Carmarthenshire County Council as a part of the Millennium celebrations. This is an unusual history, as it looks at the origins of all the streets of Ammanford along with their notable buildings and people. A history of Ammanford's bricks and mortar, it nevertheless contains a pretty comprehensive history of the town. Although there is little on its social or political history, it is the most detailed and comprehensive book on Ammanford to date. For those born and brought up in Ammanford, memories will come flooding back as you browse. Mr Locksmith has also kindly provided information on Iscennen and Treforis by letter.

1 AMMANFORD CARNIVALS 2 THE HOUSING ESTATES Iscennen 1921 Caemawr 1947 Carregamman 1948 Myddynfych 1949-1951 Treforis 1950s Parcyrhun 1956 Heol Wallasey 1957 Gwynfryn 1980