THE DUBUISSONS OF GLYNHIR

A CARMARTHENSHIRE HUGUENOT FAMILY

CONTENTS

A Carmarthenshire Huguenot Family

Endnote – Glynhir Today

CADW Survey of Glynhir:

(1) Glynhir Mansion

(2) The Dovecote

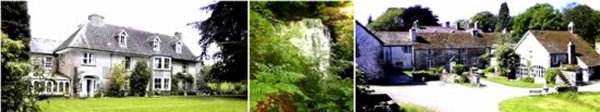

(3) The Ice HouseGlynhir Mansion today is a hotel set in its own picturesque grounds and woodlands on the banks of the river Loughor, just two miles from Ammanford and Llandybie. The estate includes the highest waterfall in Carmarthenshire, where the Loughor conveniently plunges thirty feet over a rocky outcrop just behind the mansion. Glynhir has, appropriately, a long and equally picturesque history, thanks largely to one family of French Huguenot (ie Protestant) origins who resided there from 1770 to 1921. Here, from the Carmarthenshire Antiquary journal of 1945, is a brief history of this family, followed by an update of the mansion's fortunes after 1921.

A CARMARTHENSHIRE HUGUENOT FAMILY

[THE DU BUISSONS OF GLYNHIR, LLANDEBIE]

By T. H. LEWIS, M.A., H.M.I.

First published in

The Carmarthen Antiquary II

(1945–6), pp.10–23The Du Buisson family, which was of Huguenot extraction, settled in Carmarthenshire in 1770 and was associated with the County (at Glynhir, Llandebie) until the year 1921. Much of its history is obscure but sufficient of it is now known to justify an attempt to give a fairly coherent account of its activities and to amplify the fragmentary references which have hitherto been made to this interesting family.

According to the Du Buisson family papers, the original member of the family to settle in England was Pierre Grostéte, "Sieur du Buisson", a Huguenot who had fled from the Orleans district to Hanover Square, London, about the time of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685). (See Note 1 below) There were however Frenchmen of the name of Du Buisson in England before the year 1685, including some at Wandsworth with which the Du Buissons of Glynhir had some associations. (Note 2) Among the "Letters of Denization and Acts of Naturalization for Aliens in England and Ireland, 1603–1700", there appears the name of Peter Du Buisson who was granted denization on June 22nd, 1694. (3) As there is no reference to his wife or children it may be inferred that he was the Peter (Pierre) Du Buisson who came over from France, when quite young, in 1685. The family genealogical table gives Peter Du Buisson (who settled in Glynhir) as the son of the original emigrant, Pierre Grostête, but in the Appendix to his book on "The Huguenots", Samuel Smiles refers to Peter Du Buisson as a grandson who "bought an estate in South Wales which one of the branches of the family still occupies." (4) Pierre Grostête was naturalised in 1706. (5) In 1707 a "Peter Dubison" resided at Wandsworth and on the 19th November, 1715, was granted a patent for "dyeing …" (6) Further particulars of this patent are given by another authority:

"On November 19, 1715, to Peter Dubison was granted a patent (No. 400) for a new peculiar way of printing, dyeing or staining of calicoes in grain, with colours more bright and lasting, and which shall bear washing and weather much better than any heretofore used in Europe and that such calicoes shall equal, if not exceed, in beauty and use, those stained in the Indies." (7) There is no evidence to show whether this was Pierre Du Buisson, the refugee of 1685.

It was by accident rather than by design that the family settled at Glynhir. Peter Du Buisson, while on his way to Ireland, was detained by bad weather in 1770. Taking advantage of this delay to visit the surrounding countryside he was so charmed with the beauty of the Glynhir district, Llandebie, that he bought the Glynhir estate which was then for sale. The ' Notice of Sale' read as follows:

'To be sold by Auction, at the Turnpike House Inn, in Llandilo, Carmarthenshire . . . on Tuesday the 8th May next; the Freehold Estates hereundermentioned, in one or four lots, all lying within a Ring Hedge in the parish of Llandebie . . . and near the Turnpike Road leading from Llandilo to the seaport towns of Neath and Swansea …

"Lot I The Capital Messuage and Demesne of Glynhir, consisting of a good Mansion-house, all convenient Offices and outbuildings fit for a gentleman's family, with 71 acres 3 roods of pasture and 33 acres and 17 perches of Woodland, occupied Time immemorial by the owners. As there is a Command of a large and constant stream of water running through the farmyard, and as coal and lime may be delivered upon the farm at twopence per bushel, its yearly value may be moderately computed at £70. Great improvement were by the late owner made in this demesne, which is yet capable of much greater in point of profit as well as beauty its natural beauties are not unworthy of notice, particularly an agreeable prospect of a fine vale down to the sea, and a much-admired cascade, formed by the river Lochor, in a grove adjoining to the garden.

A well-accustomed Water Corn Grist-Mill, near the Mansion House, never rented, yearly value about £8.

Lot II A farm, called Nant-hire, consisting of 69 acres and 22 perches of Arable, Meadow and pasture land, let to Rees Evans, at the low clear yearly rent of £10 10s.

Lot III A small farm, called Hendre-Iago, containing 17 acres 3 roods and 10 perches, of amble, meadow and pasture land, rented to William Griffith, at the low yearly rent of £5 5s.

Lot IV A small tenement, called Waindraw, consisting of 14 acres and 20 perches of arable, meadow and pasture, let to John Morgan Owen, at the yearly rent of £5 5s.

NB The timber, cordwood and bark upon Lot I are to be valued. All the buildings are in good condition, the several farms well inclosed, and have a right of common without stint on extensive hills in the neighbourhood. There is coal under Lots I and II but not worked at present."

For the Glynhir estate, Peter Du Buisson paid £33,000, a substantial sum of money at that time. The 'late owner' referred to in the above 'Notice of Sale' was Richard Powell – or 'Powell, Gent' as he is described in Kitchin's Map (1754). One letter sent to Peter Du Buisson on March 27,' 1770, 'by Chas Powell ' (possibly somebody acting on behalf of Peter Du Buisson) gives further details of Glynhir. Wages in the locality were 7d. an hour. Tithes on corn, lambs and wool were paid in kind. As for the rest, a sum of 2d. a cow was paid in lieu of sheep and 2d. a farm in lieu of Tithe Hay-Rates, and Taxes were not more than ten guineas. Owing to the wet weather locally it was not possible to "bring turnips or any other new husbandry to any perfection. In the Deed of Agreement, Peter Du Buisson is described as 'of Newlands (Glos.) ' — presumably he had been living there. (8)

It is of interest to note that the Moravian Body was also considering the matter of acquiring Glynhir. (9)

One letter sent to Peter Du Buisson (March 26, 1770) by a certain William Thomas refers to a flood which "did damage the Forge a little." (10) This raises the question of what connection there was between the Du Buisson family and the Llandyfân forge – for that was probably the forge referred to in this letter.

As the 'Notice of Sale' contained no reference to any forge or iron-works at Glynhir, it may be assumed that the 'knife-works' for which Glynhir became afterwards well-known were set up by Peter Du Buisson. These works were situated in a glen near Glynhir and their ruins (which must not be confused with those of Glynhir Mill, a little higher up the glen of the Loughor) may still be seen. They were fed by water from the river Loughor. (11)

The Llandyfân forge was quite a separate concern and was situated in the upper reaches of the Loughor, near Carreg-cennen Castle. There is no foundation for the view that the Llandyfân forge was founded by Peter Du Buisson. This forge is clearly shown in Kitchin's Map (1754) which was issued before Peter Du Buisson came to Carmarthenshire. According to local Tradition, Llandyfân Forge was of great antiquity. (12) That might very well have been so, for the district around Carreg-cennen Castle was the "maerdref" of the Commote of Iscennen, and as a forge was important in medieval times it is not impossible that craftmanship in iron persisted locally. It is difficult to see what economic advantages were offered by the site of the Llandyfân forge. The suggestion that "Here, there were good supplies of timber, coal, iron-ore and limestone, the essentials of the iron industry" is misleading. (13) Some timber was certainly available in the locality, but Thomas Edwards (Twm o'r Nant) states in his 'Autobiography' how he used to haul timber to Llandyfân from Abermarlais, in the Towy Valley. There was no coal in the immediate vicinity. The old practice of using charcoal rather than coal persisted much longer locally than in more progressive areas. There is every reason to believe that no coal was used at Llandyfân during the eighteenth century. It is possible that some amount of iron-ore was obtained within easy reach of the Forge but local tradition and other evidence indicate that iron-ore was brought to Llandyfân from further afield. Pig-iron was conveyed by mules to Llandyfân from the Ynyscedwyn Works (Swansea Valley) but when the owner of those works had acquired a forge at Clydach he relinquished his connection with Llandyfân. No supplies of pig-iron, it is stated, came from Ynyscedwyn to Llandyfân after about 1780, except one article which was sent about 1783. (14) The Loughor river provided ample water-power. In his "General View of Agriculture", Walter Davies (Gwallter Mechain) stated, in referring to this river "Its copiousness some years ago induced the proprietors of the Ynys Cedwyn ironworks to erect blast furnaces upon it to smelt ironstone brought from the banks of the Tawy over several miles of mountainous roads". (15). Close to the Forge is the Glan Quay Inn – the 'quay' being the stage-work for loading the pack-saddles. (16)

The owner of the Llandyfân forge towards the middle of the eighteenth century was Robert Morgan, the Carmarthenshire iron-master (1708–77). The Forge produced 100 tons of bar-iron in 1750. The heating of the pig-iron was done in an open hearth, fed with charcoal, and furnished with bellows. Then the pig-iron was placed under a high hammer worked by a water-wheel and ultimately beaten into bars. All the various processes were done at the Forge. An inventory of stock taken at Llandyfân Forge in 1799 contains references to sacks of charcoal, bellows and various types of timber. (17)

Local tradition associates the Coslett family with the actual working of the Forge in its early days. A descendant of this family recently asserted that the Llandyfân Forge was started in 1720 by three Coslett brothers and that one reason for the site of the Forge was the flow of water over limestone, which "is invaluable in the tempering of steel." (18)

There is a reference to "Samuel Corsled" in the Llandebie Parish registers for 1777. It is not quite clear where this Coslett family came from. (19)

In his "Tours in Wales" (circa 1785–90), Richard Fenton has the following reference to Peter Du Buisson "Hence to Glynhir, the seat of Mr. Du Buisson who came to this country concerned in an iron work which was carried on by the river Lochor which passes through the farm of Clynhir now made by great perseverance and profound agricultural knowledge from hard mountain ground into as good as any in the county". It is not quite clear what was the 'ironwork' that Fenton had in mind. A map of Glynhir in 1790 is still in the possession of the family. The house was smaller than that it is now, and the outbuildings also were fewer. In the early part of the nineteenth century, Glynhir was largely self-supporting. It had its own brewery, laundry, slaughter house, smithy, carpenter's shop, mill and columbary. (20)

Although Peter Du Buisson was not the owner of Llandyfân forge he undoubtedly set up a 'knife-works' at Glynhir. There were several Glynhir-made knives in the possession of Llandebie folk within the present writer's memory and one specimen may be seen at the museum at Carmarthen.

In an unpublished essay which was submitted for competition in 1896 at a Llandebie Eisteddfod on the subject, "The Industries of Llandebie," reference is made to the "Knife-works" at Glynhir. According to this essay, the "factory" was a building of about 100 square yards – something like an "old-fashioned cowhouse" and it was started by a French company at the instigation of Peter Du Buisson. All the workmen came from France. Near the "works" was a confectioner's shop built by a Frenchman who had to go every week to Neath market with his cakes. According to this essay, there was still to be seen at Llandyfân Forge a whetstone formerly used at Glynhir. (21) Although these statements are not wholly accurate they reflect some of the ideas prevalent locally about Glynhir.

There arises the question as to why the Du Buissons set up a "knife-factory" at Glynhir. As a body, the Huguenots were generally skilled in various crafts but the Du Buissons were presumably of the landed class in France and they were landed gentry in Carmarthenshire.

The Du Buissons were closely associated with the Henckell family, of Wandsworth. James Henckell, 'of the City of London, merchant,' spent much of his time at Glynhir and died there on January 10, 1823, aged 84. His daughter Caroline, married William Du Buisson, the son of Peter Du Buisson. (22) Some members of the Henckell family were engaged in the iron industry at Wandsworth. According to a Wandsworth historian, "Mr. Henckell's Iron Mills stood where are now the Royal Paper Mills. Of this place Dr. Hughson writes in 1808, and says, 'Here are cast shot, shells, cannon and other implements of war.' (23) The Henckells had also a copper mill near Wimbledon in 1792. (24) This family, like the Du Buissons, was of foreign extraction and was of Dutch origin. (25) It is possible that Peter Du Buisson was interested in the iron industry before he came to Glynhir but this step may perhaps have reflected the influence of the Henckells. (26)

Local tradition very definitely asserts that the Du Buissons were in close touch with France during the 1789–1815 period, and this tradition can be safely accepted. But it is difficult to accept the suggestion that the family acted in an unpatriotic spirit.

Local stories suggest that the Du Buissons 'were favourable to' their native land, that arms were made at the 'factory' and smuggled to France and that use was made of pigeons for maintaining treasonable relations with France.

The facts however suggest another explanation although it is easy to understand that in such a disturbed and tense period it was natural to suspect anybody of foreign origin. Glynhir certainly had a large dovecot but it was not unusual for country houses, until the development of winter feeding for animals, to keep a large number of pigeons as a means of providing supplementary food.

It would not have been surprising had the Du Buissons been at first favourably disposed towards the French Revolution which brought about the fall of the dynasty under which the Edict of Nantes had been revoked. Smuggling was certainly very common in the Napoleonic era. But Peter Du Buisson had been born and bred in England, had ceased to belong to the Huguenot Church and had become thoroughly Anglicised. The tablet in his memory in Llandebie Church refers to his "long and faithful discharge of every moral and official duty, as a Magistrate and Publick Servant" and to his ' religious and well-spent life.' Although such encomiums need not be taken too literally, the obituary notices in the "Carmarthen Journal" and the "Cambrian" referred to him as the "Receiver-General for the Counties of Carmarthen, Pembroke and Cardigan", a post which (according to the "Cambrian") he had held 'for many years.' The "Journal" further added "Residing upon, and farming, his estate, Mr. Du Buisson had the happiness of being enabled to diffuse among his numerous dependants the blessings of competence and comfort; and by a firm adherence to the dictates of justice, tempered occasionally by the suggestions of mercy, he deservedly acquired the estimable character of an upright magistrate and a benevolent man". (27) As a Receiver-General, he was in full charge of the taxes for the three counties indicated, and one may assume that his loyalty was beyond doubt. According to one story, however, Peter Du Buisson was a close friend of David Jones, the Carmarthenshire drover who founded the well-known Black Ox Bank in 1799, and they were both engaged in smuggling arms illegally into France. A quarrel ultimately arose between them and, as a result, Peter Du Buisson founded the Bank of Glamorgan. In revenge, David Jones informed the authorities of the cutlery works at Glynhir and of Peter Du Buisson's relations with France. News, however, came to Glynhir in time to enable the cutlery works to be dismantled and for the machinery to be transferred to Pontlliw before a raid, was made by the Dragoons on Glynhir. As a climax to this reference is made to a "recent discovery in the grounds of Glynhir", namely that of a stone-lined circular pit, about 40 feet deep and of the same excellent workmanship as the piggeries and stables which were built at the same period. This pit, which had a trap-door and a secret exit into the Loughor dingle was (it is suggested) constructed and used for the hiding of French spies and of contraband and weapons of war.

This story needs to be disentangled. Although no definite documentary evidence as to the connection between Peter Du Buisson and David Jones has yet come to light, it is probable that they had no close business relations. In the obituary notice on Mrs. Du Buisson, there is a reference to Peter Du Buisson as "a partner in the banking-house of Landeg and Co. in Swansea." (28) This banking-house was also known as the Glamorgan Bank. (29) As the Black Ox Bank was founded in 1799, it is clear that Peter Du Buisson did not long remain on good terms with David Jones, the Banker.

It is difficult to accept the statement that the Dragoons raided Glynhir at the instigation of David Jones. Equally unacceptable is the suggestion that the activities at Glynhir were carried out in secret. If any such raid were needed, it would most likely be carried out by local "territorial" troops and not by regular troops whose services would be more urgently required elsewhere. Carmarthenshire had its own local troops – its Volunteers, Militia and Fencibles. Llandebie itself had its own troop of Volunteers. (30) In those days, Llandebie was a definitely rural parish and Glynhir was not more isolated than any other part of the parish. To have carried on any secret activities for some time would have been very difficult. There is no mystery about the stone-lined circular pit. It is certainly not "a recent discovery" for it has, for many years, been well-known to those who are familiar with Glynhir. It had been used for many years as a game-house and was known as the "Ice House". Although the site is now covered with trees, it used to be an open space.

There is much circumstantial evidence that the Du Buissons were in close touch with France during the 1789–1815 period. Local tradition asserts that the 'goods' were carried by mules to Pembrey by way of Pentregwenlais and Trimsaran. The Mynydd Mawr area had not been enclosed in the eighteenth century and the route indicated by local tradition was the one normally taken in those days.

Britain secretly aided certain elements in France that opposed the French Revolution. Later, when Napoleon took control and endeavoured to weaken Britain by stopping British trade with various European countries it became a patriotic duty to break the blockade and smuggle goods into Europe. The products of the Glynhir factory (and also of Llandyfân Forge) might well have been used for this purpose. Caroline Du Buisson, who lived at Glynhir in the Napoleonic era, is known to have said that Pembrey was well-known for smuggling in those days.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this tradition is the story that the Du Buissons were the first people in this country to hear of the result of the Battle of Waterloo. Although this at first may appear to have little foundation, it is probably true. The present writer well remembers in Llandebie many old persons who could remember that battle and whose statements should bear some weight.

This is the story as given by one who was bred and born at Glynhir, and as he heard it from his father and grandfather who had both spent their lives at Glynhir. (31)

Peter Du Buisson had two young nephews from France staying in Glynhir when the news came that Napoleon had escaped from Elba. They were immediately recalled to France and took the pigeons with them. Hence, the news. Then Caroline Du Buisson (was Peter Du Buisson then dead?) went on horseback by relays to London to the Rothschilds.

Peter Du Buisson had died towards the end of 1812. The lady afterwards known as Caroline Du Buisson was then known as Caroline Henckell, daughter of James Henckell, "of the City of London, merchant". Peter Du Buisson himself was "late of Hanover Square, Westminster". Nathan Rothschild had recently settled in England and was already in the confidence of the British Government. Like many other British merchants he had taken some part in contraband activities against France, but from about 1810 onwards he had acted in various ways for the British Government. It was he who was responsible for getting money supplies secretly by way of France to Wellington in Spain. He had many agents in his service. So efficient was this organisation that Rothschild obtained news quickly in days when news travelled slowly. His success gave rise to many romantic tales, but there is every reason to believe that he organised an efficient pigeon postal service. (32) So far as is known, the details of this Rothschild organisation have never been disclosed by that family. But it was quite possible for the Henckells and the Du Buissons to have been in touch with the Rothschilds. One Llandebie story credits Caroline Du Buisson with being a friend of Mrs. Rothschild. This assertion is probably true – Mrs. Nathan Rothschild was the daughter of a London merchant who had emigrated from Amsterdam. The subsequent history of Caroline Du Buisson suggests that such a rapid and long ride to London would not have been beyond her powers, as a young woman. It is not unreasonable therefore to suppose that the Du Buisson family formed one link in the Rothschild organization which was directed against Napoleon. That would explain the secrecy of its activities and the increased importance of the Du Buissons after the battle of Waterloo. It is well-known that the Rothschilds knew the result of the battle of Waterloo before the British Government did. Various stories have been related to explain how this was done but the part taken by Caroline Du Buisson is probably the true reason.

The reference to the "nephews from France" raised an interesting question which it may perhaps be impossible to answer, namely the identity of those in France with whom the Du Buissons were in touch.

The surname 'Du Buisson' is not one of the commonest of French names. Only two of that name are usually mentioned in the standard historical accounts of the 1789–1815 period. There was a certain Paul Ulrich Du Buisson (1746–1794), an extreme Jacobin, who was guillotined with the Hebertists. He was a man of letters who played an active part as a secret agent (chiefly in Belgium and Switzerland) of the Freys and other speculators, and who was mixed up in foreign affairs and sent on many secret political missions. (33) He was a member of the Cordeliers Club. The charge brought against him and the other Hebertists was that they were agents of foreign powers ('agent de l'étranger'). The Freys were Austrian Jews who kept in touch with their brothers in Vienna.

The other Du Buisson referred to was of a somewhat different type, but he also was concerned in some curious activities. General Malet, after spending some time in prison, obtained leave in 1812 to move to the 'home' kept by Dr. Du Buisson at the further end of Faubourg Saint Antoine. There, Malet got acquainted with several other political prisoners to whom the same privilege of living under the doctor's surveillance had been granted. Almost all of these were royalists or clericals (including the two Polignacs) that is, they were opposed to Napoleon. A new plot was then formed "with the aid of certain young men who visited the prisoners while under the doctor's roof". (34)

There is no definite evidence, however, to indicate that there was any connection between these Du Buissons and the Glynhir family.

Finally, there arises the question of the closure of the Glynhir 'factory'. Local tradition suggests that it ceased to exist after the Napoleonic War and this appears to be in accordance with the facts. But there is no basis for the supposition that the end of the Glynhir 'factory' was the beginning of the Pontlliw Forge (near Pontardulais). The Glynhir 'factory' appears to have been still in being in 1812, for at the beginning of that year, a certain John Howells pleaded guilty at the Carmarthenshire Quarter Sessions to a charge "of stealing iron from Mr. Du Buisson". (35) The persons associated with the Pontlliw Forge were the Cosletts, who had also been associated with the Llandyfân Forge. The date sometimes given for the establishment of Pontlliw Forge is 1740. (36) But it is difficult to accept that statement. Kitchen's map (1767) refers to "Llue vill and mill" but not to any Forge. One may hazard a guess that the rise of Pontlliw Forge was associated with the decay of Llandyfân Forge, which had certainly ceased to operate before the present writer's grandmother (born 1834) could remember. Things were in a bad way at Llandyfân in 1808. The Cambrian newspaper for August 20th of that year contained the following notice of sale "Lot 2 By order of the assignees of Win. Roderick, a bankrupt, at George Inn, Llandilo . . . together with a forge, lately used for the manufacturing (of) iron, store, and charcoal houses, two dwelling houses for workmen, a stable and other conveniences lately erected thereon". Some members of the Coslett family still lived in the Llandyfân district as late as 1827. In a small book, containing the names of the pupils at the Banc-y-felin (Glynhir) School, there is a reference for that year to "Mary Coslett Mountain, or rather Forge." (37) This Forge was a small building on the road near "The Square and Compass," not far from Glynhir. In the official Journal of the Ivorites' movement ("Yr Iforydd") for 1841, there is a note of the marriage of "Mary Cosslett, the only daughter of Mr. Cosslett, Llandyfaen", – probably the same person as the Glynhir pupil. But the same volume of the "Iforydd" refers to a "Coslet Coslet" of Bettws and to a "Thomas Coslett" of Llandilo-Talybont, – that is, the Pontardulais-Pontlliw district. Members of the Coslett family still live in Bettws and Pontlliw. As the Ordnance Survey for 1831 clearly marks a Forge at Llandyfân, it may be assumed that the building, at any rate, still remained on that date. It is clear however that some part of the Coslett family had settled at Pontlliw not later than 1820, for an advertisement in The Cambrian for that year (May 23) announced the sale of "a leasehold tenement and lands called Pandy, situated in the said parish of Llandilo-Talybont and now in the occupation of Thos. Coslett and David Jones". The premises included an Iron Forge, that is the Pontlliw Forge. The Baptist cause at Pontlliw is stated to have been started in the Pontlliw forge in 1832; (38) the Cosletts of Llandyfân were Nonconformists. With the Coslett family at Llandyfân is associated the White family a Miss White married a Coslett at Llandyfân. In 1809, the country house of Cefn Cethin (near Llandyfân) – the property of Lord Robert Seymour – was in the charge of John White. (39) It seems likely that the Llandyfân forge languished after 1808. Gwilym Teilo, writing in 1858, stated that Llandyfân was working about 50 years before that date and that the Forge had stopped working because it was undermined by an unusual flowing of the river. (40) The increasing use of coal for smelting had probably militated against Llandyfân. As the Glynhir 'factory' doubtless got some of its iron from Llandyfân, this may have been one reason for the closure of Glynhir.

There is clear evidence that the Du Buissons gained in influence in the County after Waterloo.

Peter Du Buisson was succeeded by his son, William Du Buisson, who was one of the subscribers to the Picton. Monument Fund in August 1815 and was appointed a Deputy-Lieutenant of the County in November of the same year. (41) William Du Buisson was High Sheriff in 1826. (42) He "departed this life at his brother's house at Wandsworth... on the 3rd of November, 1828, in the 47th year of his age after a long and painful illness". A local bard extolled his virtues and public spirit:

"Mewn dagrau rwy'n anfon trwy'r gwledydd o'r bron,

Am orchwyl wnaeth angeu ar DuBuisson;

Bu'n dyoddef mawr gystudd poen dirfawr a chur,

Ond dianc wnaeth trwodd, mae'n galled i'r sir.Bu'n hynod ddefnyddiol tra parodd ei daith,

Mewn bydol orchwylion, i weithwyr gael gwaith,

A phlwyf Llandebie mewn galar mawr sy,

A'r gweiniaid yn ochain yn uchel eu cri.Mae cannoedd o fechgyn a merched bach hardd

A gododd i fyny fel egin mewn gardd;

Rhoi ysgol a llyfrau a gwisgoedd i'r gwan,

Rwy'n credu heb ammheu mai mawr fydd ei ran. (43)Translation (made for this website. © www.ammanfordtown.org.uk, 2004)

In tears I send to all the news

Of hapless DuBuisson's demise,

Affliction great and pain he bore

Until he slipped this earthly shore.In worldly terms his loss is grave

Since work to local folk he gave.

Now Llandybie's grief is great,

The poor and weak bemoan his fate.So many boys and girls we know

Like garden buds, he helped to grow.

School, books and clothes were his bequest

And heaven, I'm sure, is where he'll rest.He was followed by his son William Du Buisson (1818–94), who was a High Sheriff of the County in 1870–71. He was escorted for a week's term of duty by twelve Glynhir tenants, each with his "wig" and 'javelin". It appears that this was the last occasion on which a Carmarthenshire High Sheriff was accompanied by such an escort His widow, Mary Du Buisson, died at Torquay in 1918, at the age of 92.

The dominating figure at Glynhir during the early half of the nineteenth century was undoubtedly Caroline Du Buisson, wife of the first William Du Buisson. It was she who set up a school for girls at Banc-y-felin near Glynhir and who fostered the school at Llwyndyrys (near Llandyfân). The rebuilding of Llandyfân Church and the renovation of the Llandebie Parish Church were also largely her work. Her personality made a deep impression upon the life of Llandebie. When she died at Glynhir on May 30, 1869, aged 81, the log-book of the Llandebie National School recorded how the school had lost its main supporter.

A Glynhir sampler sewn by Margaret Davies in 1843. The motto embroidered into the sampler is from Genesis chapter 2, verse 25, and reads: "And they were both naked the man and his wife and were not ashamed" Below that is another Biblical quote from Psalm 107, verse 31: "O that men would praise the Lord for his goodness and for his wonderful works to the children of men." The sampler is signed at the bottom: : "Margaret Davies Aged 12 1843."

The sampler is currently in the possession of Margaret Hillyer nee Evans, a descendent of Margaret Davies, currently living in Western Australia.In 1911, Mary Du Buisson wrote her "Recollections of Glynhir" and these notes are still preserved in the family papers. She had spent 42 'happy years' at Glynhir and had had ample opportunities of knowing Caroline Du Buisson very well. She refers to the part taken by Caroline Du Buisson in the rebuilding of Llandyfân Church. That edifice, for some time, had been used by Nonconformists but Dr. Griffiths (the Vicar of Llandilo) had "rescued" the place. The "Recollections" refer to the Banc-y-felin Girls' School set up by Caroline Du Buisson. It had about 30 pupils and a Lending Library from which books were issued once a fortnight. The girls were given a cloak every year to last for the winter. The School uniform was a grey cloak and a hood with a red border. Unlike most schools of that time, the schooling was free. The curriculum consisted of Religious Instruction (including the learning of the Collect for the ensuing Sunday), "Christian Faith and Duty", Arithmetic, Writing, Geography and Needlecraft. The pupils had to read a chapter from the Old Testament in 'Welsh three times a week. Extracts from "Cannwyll y Cymry" were also read. Every Sunday morning, the pupils were expected to assemble at the Llandebie National School at half-past nine, and then to proceed to morning service at the Parish Church. Each girl was presented with an English Bible and work-box on the Ash-Wednesday following her departure from school. The making of samplers formed part of the Needlecraft course. Many of the Glynhir samplers are still to be seen in Llandebie homes. The school had two clothing clubs, one for young women (about 8o in number) and one for the pupils. It continued until I894. (44)

William Du Buisson was succeeded by his nephew Arthur Edmund Du Buisson (1860–1930). He is still well remembered by the older folk of Llandebie as an enlightened country squire who took an active interest in local movements. In the first World War his son, John Edmund Du Buisson, died at Salonica. After the War, the Squire of Glynhir left for Sussex and afterwards for Hartley Whitney (Hants.) where he died in I930. (45)

Most of the Glynhir estate was sold in 1921 and thus was closed a connection of about 150 years with the parish of Llandebie. Only the memorial tablets in Llandebie Parish Church now remain to remind the district of the Glynhir family.

NOTES

ABBREVIATIONS USED

A.V.C.: Amman Valley Chronicle.

C.: The Cambrian newspaper.

D.P.: The Du Buisson papers.

Hist. Carm. : A History of Carmarthenshire : (Ed. Sir J. E. Lloyd).

J. : Carmarthen Journal.

P.H.S. : The Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London.FOOTNOTES

(1) The 'Du Buisson papers' are in the possession of Mr. W. A. Du Buisson (London), the younger and sole surviving son of the late Arthur E. Du Buisson, who was the last member of the family to occupy Glynhir. The present writer has been kindly permitted to see these papers.

(2) In "The Registers of Wandsworth Surrey" (J. T. Squire) for 1603–1787 there are the following references :– (pre-1685)

.......Christenings. p. 102, 1681, May 15th: Elizabeth, daughter of Peter Debbison.

.......p 109, 1686–7, July 24th: Peter Debuison.

.......Burials. p. 345, 1670–1, March 16th: Elizabeth, wife of Peter Debuison, Dyer.

(3) "The Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London" XIII, p. 234.

(4) Samuel Smiles mentions another Huguenot refugee of the same surname, namely, "Francis Dubuisson: a doctor of the Sorbonne".

(5) Pierre Grostéte did not come to Carmarthenshire but his wife, Jane, died at Glynhir, Llandebie in 1772, at the age of 72. In the "List of Foreign Protestants and Aliens Resident in England, 1618–1688" (W. Durrant Cooper), the only reference to anyone of this surname is "Isaac Dubuisson".

(6) Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London". I, p. 238. The name is variously spelt in these records.

(7) Davies "Industries of Wandsworth, Past and Present". p. 8.

(8) DP

(9) Cylchgrawn Cymdeithas Manes Eglwys Methodistiaid Calfinaidd Cymru (Sept. 1936. pp. 66–68). The widow of the former owner of Glynhir died in May, 1807 at Llandilo (aged 80) – "a superior understanding and fine person, a Liberal benefactress to the poor." (C. May 30, 1807).

(10) DP

(11) 'Cati Pentwyn' who was born about 150 years ago and who lived to be nearly 100 years old used to say that, when she was a girl, there was a large pond with two swans on it near the Glynhir "knife-works". This part is now covered with trees. The outlet from the lake runs into the river. A row of chestnut trees was planted by William Dubuisson, just after his marriage, to celebrate the Battle of Waterloo.

(12) Lewis Price Guide to Llandilo p. 22.

(13) Hist. Carm. II. p. 327.

(14) Roger Thomas Traethawd ar ddechreuad a chynydd Gweithiau Haiarn a GloYnyscedwyn ... (1857). In Clydach a'r Cylch (T. V. Evans) there is a reference to an individual who used mules for conveying iron to and from the forges at Clydach and Llandyfrmn. (p. 22).

(15) I. p. 110.

(16) J. T. Edwards AVC. Feb. 26, 1920.

(17) Hist. Carm. II. p. 327.28 (It is not quite clear how this statement fits in with Gwallter Mechain's assertion).

(18) A.V.C.

(19) In A.V.C. for Feb. 26, 1920 J. T. Edwards stated that the Cosletts came from Nottingham. Local tradition suggests they were of Belgian extraction.

(20) Neath Guardian, March. 5, 1937. (Based largely on information supplied by Mr. W. A. Dubuisson.

(21) D.P.

(22) His widow, Elizabeth, died at Glynhir, on October 25, 1832, aged 85; and his daughter, Maria, died at Swansea on April 28, 1821. James Henckell's wife was the sister of Margaret, the wife of Peter Du Buisson (Sir J. Bradney A History of Monmouthshire IV. p. 155).

(23) Davies op. cit. p. 28.

(24) Malden Victoria History of Surrey II. p. 414. In 1811 this mill was no longer owned by the Henckells.

(25) According to the Letters of Denization and Acts of Naturalization (P.H.S. XIII. p. 238 and p.251) a certairn Abram Henckcll was naturalized its March. 1697–98. His brother, Jacob, belonged to the Protestant Church in London. According to Hone's Year Book for 1832 (pp. 1339–40) a certain "William Henkels" was among a group of Foreign Sword-cutler, who fled to Britain about 1690 for the sake of religious liberty. It is not quite clear whether these belonged to the same family as the Henckells who came to Glynhir.

(26) The firm of Henckell Du Buissors and Co. still exists in London.

(27) His wife, Margaret had died June 18. 1804, aged 57 years.

(28) C. July 14, 1804.

(29) Swansea Guide (5802) p. 8. The head of this bank was Roger Landeg.

(30) C. April 21, 1804. "On Thursday, the 5th inst., the Rev. Thomas Beynon gave an excellent entertainment at Llandybie to the volunteers of that neighbourhood, commanded by Capt. Edwards. The Field Officers of the battalion likewise partook of an elegant repast, provided by the same gentleman". (The Rev. Thomas Beynon was, presumably, Archdeacon Beynon, Llandilo. Capt. Edwards was "Thomas Edwards, Gent., of Derwydd, Llandebie.")

(31) Mr. D. L. Davies, The Bon, Swansea.

(32) e.g. John Reeves: The Rothschilds, p. 168.

(33) See, for example,

.......Morse Stephens : Orators of the French Revolution, II, p. 532.

.......Pierre Gascotte : The French Revolution, pp. 373–75.

.......Lavisse: Histoire de France Contemporaine, II, p. 187.

(34) Cambridge Modern History IX, p. 543.

(35) C.: January 8, 1812

(36) According to a local historian – Mr. H. T. Clee, Pontlliw.

(37) D. P.

(38) Mr. H. T. Clee, Pontlliw. – to whom I am indebted for information about Pontlliw Forge. The grandson of the above Thomas Coslett died only recently. He informed Mr. Clee that his grandfather had left Llandyfhn Forge for Pontlliw during the Napoleonic War.

(39) C. December 23, 1809

(40) Davies : Llandilo-Vawr and its Neighbourhood. (1858).

(41) C. August 19 and November 11, 1815.

(42) Seren Corner: 1826, p. 90.

(43) Seren Corner: 1829, p. 28.

(44) Probably the oldest living pupil of this school is Mrs. Richards, Waunlwyd, Saron, Llandebie, who was at Banc-y-felin School under Mrs. Harris, the first Head Mistress. Mrs. Richards is in her 95th year.

(45) A brother of Arthur Dubuisson was the Very Rev. J. C. Dubuisson, Dean of St. Asaph, who died in 1938.END OF CARMARTHENSHIRE ANTIQUARY ARTICLE

ENDNOTE – GLYNHIR TODAY

Local historians have been attracted to the history of Glynhir estate by the romance of the DuBuisson family. But there is another reason for all this interest, one so obvious that it's often overlooked – it still exists. This can't be said of most of the grand houses of Wales, and what few have escaped the bulldozers now lie in ruins, or survive only as hotels and old people's homes. Those few great houses that still stand in their original condition owe their second chance to the lifelines offered by public ownership and tourism.

This was the fate of the nearby Dinefwr estate and its stately home, Newton House, when it was sold by the present Lord Dynevor in 1974, suffering badly thereafter and falling into near ruinous disrepair. It was occupied by squatters for some years and was stripped of many of its original features. (At one point no more than two people at a time were allowed on the top floor because the structure has been weakened by the removal of beams and joists for firewood!). Fortunately the National Trust managed to purchase Newton House in 1990, and its parklands have following piecemeal over the past thirty years. Restoration of Newton House and other features on the estate means that Dinefwr Park today is a much-visited spot on the local tourist itinerary.

Golden Grove, the Carmarthenshire seat of the once immensely wealthy Lord Cawdor, was rescued by the County Council for use as an agricultural college in 1951, but the Cawdor's even more sumptuous Stackpole Court in Pembrokeshire found no comparable saviour and was demolished in 1963. (For a fuller history of the Dynevor and Cawdor peerages click HERE.)

The third great house to be found between the Towy and the Amman valleys is Derwydd Mansion near Llandybie, which had a closer call even than Dynevor House and Golden Grove:

Historic line comes to the end of the line

LLANDYBIE, Wales - The Stepney-Gulstons have come to the end of the line.

....Their ancestral home of Derwydd Mansion, inherited through the centuries by Vaughans, Stepneys and Gulstons, is open to offers and its contents are on the block.

...."We had no children, so it really is the end, and it's very, very sad," said Joy Stepney-Gulston, the last chatelaine, whose husband, Ralph, died in March at age 79.

....Derwydd Mansion is a 42-room stone house hidden in a fold of rising ground down high-banked narrow lanes in southwestern Wales.

....Derwydd means oaks in Welsh. Gardeners know well the Derwydd daffodil, with its double petals that look green when it first blooms.

....House records start with the rise of the Welsh gentry under the Tudors in the mid-16th century and the Tudor rose appears everywhere in the mansion's rich plaster decoration.

....But romantic legend links the house to King John, who is supposed to have slept there on his way home from southern Ireland in 1210, five years before rebellious barons forced him to sign the Magna Carta.

....The house, gardens, farm, farmland and cottages - 97 hectares all told - are on the market at a starting price of $1.4 million.

....Its contents - furniture, paintings and knick-knacks worth more than $1 million - will be auctioned on Sept 15th 1998 by Sotheby's in a tent on the lawn.

....Included in that sale will be an ebony and ivory inlaid cabinet that belonged to Marie Antoinette and was given by one of her ladies-in-waiting to Eliza Gulston-Stepney after the queen was guillotined in 1793.

....Also up for grabs is a stone carving of a recumbent whippet inscribed, "Serpent, A favourite dog of Lady Stepney's, Derwydd. Died 1750."

....It won't be missed, however, by Joy Stepney-Gulston who, clasping her tabby cat named Busy Bang Bang, confided: "I never liked Serpent. I think he looks evil."

....The last to go, in a December auction of glass in London, will be a pair of 15th-century Venetian goblets, valued at up to $140,000.

...."How they got here is unknown but they may have been a souvenir of the grand tour," mused John Owen, the family lawyer, referring to that essential jaunt to continental Europe taken by young aristocrats in the 18th century to polish their education.

....Joy Stepney-Gulston, nearing the age of 73, has been "sorting out" since April, amassing bags stuffed with such items as towels, blankets, clothes and Wellington boots to be donated to the Salvation Army.(This article appeared in The Peterborough Examiner, September 5, 1998)

Derwydd Mansion was eventually bought in this auction by a wealthy businessman whose residence it has now become, though without its historic – and valuable – contents which were dispersed in a separate auction. Unlike Newton House and Golden Grove, both open to the public, Derwydd's formidable walls and locked gates proclaim 'private property: keep out' to all who pass. As of 2008 the house is up for sale again, so its future remains as uncertain as ever. Click here for Derwydd house sale.

The DuBuissons, though lesser in status and wealth than the owners of Newton House, Golden Grove and Derwydd Mansion, like them belonged to a now extinct social class called variously the gentry, or squirearchy, whose wealth came from rents and other income from land. The leading families of the gentry were usually also members of the aristocracy, like Lord Dynevor of Newton House and Lord Cawdor of Golden Grove. But even the non-aristocratic gentry families like the DuBuissons were immensely powerful in their immediate neighbourhoods, bowing only to the Dynevors and Cawdors in seniority. The gentry made up the magistrates and judges in the local courts; they made up most of the Poor Law Guardians; they were in charge of policing, held most of the administrative positions in their locality and even had their own pews in their local churches. In the days before local affairs were administered by democratically elected councils, they were the real power locally and their authority was rarely challenged in their own fiefdoms (as we've seen with Caroline DuBuisson above, the power of the gentry didn't stop with the men):

... the gentry or the squirearchy – call them what you will – were the real rulers of the country-side. They interpreted the law at Petty Sessions [i.e. magistrates' courts]; they were responsible for all local administration at Quarter Sessions [i.e. jury trials]; they constituted in fact a ruling caste, and on the social side the wives and daughters and mothers of these magistrates shared their rule. That far-reaching power of the Welsh gentry has now been completely broken, or rather removed. The County Council Act of 1887 was a blow that in Wales smote the whole class beyond recovery. Henceforward all matters of local administration were placed in the hands of popularly elected bodies, and even the supervision of the county police had to be shared with the newly created County Council. The Parish Councils Act of a few years later, though not nearly so vital in its effects, helped to complete their discomfiture ('The South Wales Squires', pages 4–5, by Herbert M. Vaughan, originally published in 1926; reprinted in 1988, with a forward by Byron Rogers, by Golden Grove Editions.)

Former squire Herbert Vaughan (1870–1948) leaves us a description, from the horse's mouth as it were, of this strata of society:

Now I consider that to be ranked as a squire in the proper sense of that term there are three qualifications necessary. First, there must be a mansion or residence; second, there must be a home-farm or demesne attached to the residence; and third, there must be an estate, no matter how large or how small, provided there are tenants of the owner of the mansion ... an estate with tenants is an absolute necessity to the true squire, who must therefore own an immediate personal interest in all land legislation, as well as in the ordinary matters of local administration ...

....The Welsh squire, as I conceive him, was rarely wealthy, although there was a certain proportion of opulent and sometimes titled landowners in Wales, who either sat in the House of Lords or who were usually elected – in the past, of course – to represent their constituencies in the House of Commons. Rather, my term is intended to apply chiefly to that once-numerous class of resident landowners in South Wales, whose incomes varied from £2,000 to £3,000 a year down to those whose estates produced an annual rental of between £1,000 and £500 ... And in this connexion it must also be borne in mind that the magistracy of the county bench was then confined solely to the landed interest. Until the present century [ie the twentieth] only those persons who owned a yearly income of £100 direct from land, or could claim a prospective income of £300 a year from the same source were eligible for the magisterial office, which meant that only squires, the eldest sons of squires, and yeomen who were fairly wealthy, could by statute be placed on the Commission of the Peace [i.e. become Magistrates] by the Lord-Lieutenant of the county.(Herbert M. Vaughan, 'The South Wales Squires', 1926, pages 3–4)

As agriculture gave way to industrialisation throughout the nineteenth century; as manufacturing, trade, the stock market, finance and the professions replaced farming as sources of wealth, the gentry slowly but surely disappeared from view and influence. Herbert Vaughan again:

Thus the status of the once all-powerful squirearchy had already been reduced to a low ebb, when the crowning catastrophe of the Great War dealt the final and fatal blow. Owing to loss in income and heavy taxation, their land was and is being put up for sale in all directions; country-seats were sold or abandoned; whilst of the squires who remained in their old homes a certain proportion has taken again to cultivating the home-farms, which had for the most part been leased or let as accommodation land. These survivors of the storm have now become gentlemen-farmers, content to stand aloof for the most part from the public life of the [magistrates'] Bench or the County Council. As an influential class, then, the old squirearchy has been practically wiped out ... In other words, it is a positive fact that, for good or bad, the Welsh squirearchy is becoming a thing of the past. (Herbert Vaughan, 'The South Wales Squires', 1926, pages 4–5.)

Most of the houses of these gentry families, great and small, have fallen before the march of time. Glynhir Mansion, too, would have disappeared under the bulldozer's advance had not it been purchased in 1965 by a family who have restored it, bit-by-bit, to something resembling its former glories:

The Du Buissons sold the estate in 1921. After this time there were a succession of owners and tenants at Glynhir who collectively allowed the estate to fall into decay. The farm buildings had become unusable due to neglect, with walls and roofs collapsing. The mansion house had deteriorated to such an extent that there was only one room that was habitable.

....In 1965 Carole and Bill Jenkins visited Glynhir and fell in love with the estate. They bought it and spent many years restoring the buildings and land. They ran the estate as a dairy and sheep farm but soon realised that they would need greater funds than the farm could provide if their work to renovate the Estate was to continue. They embarked on a programme to convert some of the redundant outbuildings into self-catering accommodation.

....Sadly some 10 years ago Bill Jenkins died. He left the continuing restoration and renovation work to Carole and their daughter Katy who, between them, run the thriving self-catering business and the country house accommodation that the mansion house provides. (from http://www.theglynhirestate.com/)

Glynhir Mansion as it is today with the nearby waterfall in the middle. It was the home of the DuBuisson family from 1770 until 1921 CADW SURVEY OF GLYNHIR

The governmental body responsible for preserving and conserving the architectural heritage of Wales is called CADW – Cadw means 'to keep' in Welsh (its English counterpart is English Heritage). In 1999 CADW conducted a survey of Glynhir and its various outbuildings and we reproduce the reports of buildings mentioned in the T. H. Lewis article above. The reports contain highly technical architectural language but are worth reprinting nonetheless.

NAME: GLYNHIR MANSION

Record No: 10,917

Locality Glynhir

Town Ammanford Post Code SA18 2TD

Community Llandybie

Authority Carmarthenshire

National Park ß0_Glynhi

Date Listed 08/07/1966 Date Amended 27/08/1999

Grade II

Location Overlooking the Loughor valley on Glynhir Road, about 2 km east of Llandybie village.

Grid Ref 26392 21512 CADW Ref EA

Formerly Listed As GlynhirHistory

The house consists of a north and a south range, of which the latter (facing the garden) is the earlier. The south range appears possibly to have commenced as a vernacular C17 three-unit farmhouse, to which a large kitchen chimney was attached at the west end. This original building was increased by the addition of a west unit enclosing the chimney and then given a steep roof with decorative eaves at the end of the C17. This was the mansion house of the Powell family until its sale to Peter DuBuisson in 1770.The house was considerably enlarged by the addition of the north range of late C18 character, probably in the time of Peter DuBuisson (d1812). The rooms of the original house were converted to reception rooms and a new front formed facing north. The north range contains the present entrance hall and stairs. The house was extended west later in the C19 to provide kitchens, offices and a conservatory, with additional bedrooms above.

Glynhir remained in the DuBuisson family until 1936. It is now (1999) being restored.

Exterior

The present entrance front of the house is the elevation north to the yard: roughcast, with slate roof; three units, the centre unit a little recessed; two storeys and an attic. In the centre unit are three round-headed sash windows, one over the porch, the others lower; Tuscan porch; pine double doors with thin overlight. Left bay: a modern unequal-sash window with small panes. Right bay: altered windows and door; two 12-pane hornless sash windows. The original windows have concealed frames and handmade glass. Three above-eaves dormer windows. To the right is a lower-roofed kitchen range with irregular fenestration.The garden elevation to the south is a four window range, including the hipped additional unit at the left. Two storeys and attic. Rendered walls and chimneys. Steeply pitched roof of gritstone tiles; deeply projecting eaves with modillions; three gabled (C20) dormer windows within the roof slope. Rendered chimneys. Fine entrance (probably Edwardian) to left with wide paired doors and sidelights with elliptical fan beneath segmental hood. Paired four-pane sash windows above. To the right are the three bays of the original house, with central canted full height bay window: four-pane window at left with hornless sashes above, modern window below. The right unit has similar four pane windows above and below. The central bay window is of two storeys, with canted sides, also with four-pane sash-windows.

The east gable elevation is slate-hung.

Interior

Good Regency dogleg staircase in the present entrance hall with bracketted cut string; swept hardwood handrail on two inch-square balusters per tread, coiled over curtail step. Ceiling cornice with shallow modillions. Decorative ceilings also in the suite of rooms to the garden front. Small vaulted cellar.Reason

Listed as a house of gentry status retaining some features of the early C18, and retaining many features of its late C18 modernisation and enlargement; the centrepiece of an exceptionally complete agricultural estate complex.Reference

T H Lewis, 'The History of the DuBuissons' in Carmarthen Antiquary II (1945–6) pp.10ff;

F Jones, Historic Carmarthenshire Homes and their Families (1987) p. 82;

Information from Katy Jenkins;

NMR incl. note by A J Parkinson;

Dyfed Archaeol. Trust SMR PRN 6905.NAME: GLYNHIR DOVECOTE

Record No: 10,904

Locality Glynhir

Town Ammanford

Community Llandybie

Authority Carmarthenshire

National Park ×7_

Date Listed 26/11/1951 Date Amended 27/08/1999

Grade II

Location At the entrance to Glynhir mansion and farmyard.

Grid Ref 26391 21514 CADW Ref EBHistory

Probably late C18, put up as one of the improvements following the acquisition of Glynhir by Peter DuBuisson in 1770. Until recently the dovecote was surmounted by an octagonal pyramid roof with a wooden cupola, and retained the complete potence.According to a strong local tradition [Lewis], the first news of the victory at Waterloo came to Britain by pigeons returning to this dovecote; Caroline DuBuisson is said to have raced to London and to her connections, the Rothschild family, with the news, to take maximum commercial advantage of this early information.

Exterior

Octagonal stone dovecote, about 6m in height, and now lacking its original roof and cupola. The stonework consists of very thin sandstone slabs, including the cambered arch over the entrance doorway. The eight corners are not differentiated from the rest of the masonry. Small string course near the head of the wall. The walls are about 0.7m in thickness, including the depth of the nesting boxes.Interior

The interior has 20 rows of eight nesting boxes in each of the eight sides apart from the entrance side, making a total of about 750 boxes. There are small landing shelves beneath each row. The base for the central revolving potence remains.Reason

A fine C18 dovecote notwithstanding the loss of its original domed roof and cupola, also listed for group value with Glynhir mansion.Reference

T H Lewis, 'The History of the DuBuissons' in Carmarthen Antiquary II (1945–6) pp.10ff; Dyfed Archaeol. Trust SMR PRN 7672.NAME: GLYNHIR ICE HOUSE

Record No: 22,226

Locality Glynhir

Town Ammanford

Community Llandybie

Authority Carmarthenshire

National Park ×7_

Date Listed 27/08/1999

Grade II

Location In the woods overlooking the Loughor valley, about 100m to the south east of Glynhir mansion.

Grid Ref 26403 21503 CADW Ref ELHistory

Probably added to Glynhir as one of the improvements following the acquisition of Glynhir by Peter DuBuisson in 1770.Exterior

The approach to the ice-house from the direction of the Loughor River, which must have been the source of the ice, is by a hollow way revetted in stone. Entrance by a low doorway with a cambered head. The doors do not survive.At the top of the dome the stonework is now exposed; complete apart from the circular keystone or grating. Much root damage to the dome and passage roof.

Interior

Egg-shaped chamber constructed in brick, reached by a short dogleg passage through doorways with missing doors. The chamber is about 5m diameter and about 4½m deep below the level of the approach passage. Iron rungs. Drainage at bottom. Domed roof.Reason

A very large ice-house in very complete condition; also listed for group value as one of an exceptionally complete series of estate buildings at Glynhir.Reference

S Lloyd Fern & P R Davies in Archaeology in Wales XXVII (1987) p.71.