Contents 1 Introduction 2 St Tybie 3 Oliver Cromwell slept here? 4 Llandybie and the Napoleonic wars 5 CADW Survey of 1966 1. Introduction

In 1911 the boundaries of the ancient parish of Betws, which had been essentially unchanged since medieval times, were extended to bring the new town of Ammanford into its embrace. The new parish created was called Betws-cum-Ammanford (Betws with Ammanford), the name stating in no uncertain terms which was the senior partner. Until then Ammanford (called Cross Inn before 1880) had been just a tiny corner of the parish of Llandybie with barely 300 inhabitants at the start of the nineteenth century. As Ammanford grew steadily in population with the exploitation of the rich seams of anthracite coal in the Amman valley, it had no church of its own, and the parish of Llandybie became responsible for the creation of the first church in the town, which was named St Michael's and All Angels (see separate history in this section). The last church to have been built in the area was St David's, Betws, as far back as the thirteenth century. By 1880 Ammanford was bigger than both Llandybie and Betws and the lack of a church was an inconvenience, even for a town dominated by non-conformist denominations. The vicar of Llandybie, the Reverend David Davies, started matters off by negotiating the temporary use of Watcyn Wyn's school, the Hope Academy in Brynmawr Lane, as a temporary church and also holding the first services there until St Michael's Church opened its doors to the faithful in 1885. Then, with the creation of All Saints in 1915, Ammanford could finally boast two churches where only thirty years earlier there had been none.

Llandybie, both the village and the church, has a far older history than the newcomer Ammanford. Legend has it that there was a church in Llandybie in the fifth century. As the name St Tybie's Church implies, there was someone called Tybie involved, who was the martyred daughter of one Brychan Brycheiniog, and who raised a church in her memory after her death.

The rule of the Romans in Wales came to an end in the later part of the 4th century AD and their legions left the rest of Britain for good in 410 AD. The Romans may have taken all of their technological expertise with them but they left one legacy that has endured to this day – Christianity. Although the Emperor Constantine had recognized Christianity in 313 AD, Roman legions and traders had already brought the new religion to Britain in the second century AD. The Romans left, but the religion they had brought hung on in some regions.

After the Romans left, the British isles were then subjected to invasions from a series of peoples. From the east came the Germanic tribes, such as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes who were eventually to become the English. From the west came the Irish, who settled and stayed in Scotland, bringing their language and Christianity to the area. The Irish also took advantage of the Roman exodus from Wales and settled in various parts of what is now the county of Dyfed. They had numerous settlements in Dyfed, and their gravestones, with inscriptions in Latin and Ogam proves that the Irish and the Britons shared the land between them. (Ogam was an ancient British and Irish alphabet.)

The area of Tirydail in Ammanford was one area settled by the Irish, the name Tirydail being said to mean Land of the Parliament after the Irish tir (land) and dail (parliament). The modern Irish parliament is also called the Dail, pronounced Doyle. There are other, Welsh and not Irish, derivations of Tirydail however. Tir (land) and dail (leaves), meaning Land of the Leaves being one. Ty (house) and dail (leaves) is also possible, giving us House in the Leaves. Pay your money and take your pick, as the saying goes.

Contents 1 Introduction 2 St Tybie 3 Oliver Cromwell slept here? 4 Llandybie and the Napoleonic wars 5 CADW Survey of 1966 2. St Tybie

This was also the period of the growth of the Christian Church, the time of Dewi (St David) and his companions. In an order to King Henry VII in the fifteenth century, in which a hundred Welsh and other Saints are invoked, St Tybie's name occurs in exactly the same time period as Saint Non, the mother of Saint David. Dewi's influence can be seen in the establishment of Bettws church, called St David's, although Bettws was established later than the main churches of Dewi. For the legend of St Tybie, the following is taken from Gomer Robert's authoritative Hanes Plwf Llandybie (The History of the Parish of Llandybie) – see the 'Books' section of this website:

"There was also another pious influence working in these parts in the 5th century, and that was the influence of Brychan Brycheiniog and his family. As his name implies, his main influence was in Brycheiniog (Brecknock), but it also reached into the centre of Dyfed, and among the religious establishments bearing the name of his family is Llandybie, in memory of one of his daughters. It was said that he was the son of an Irish Chieftain, so it is easy to believe that the Irish influence swept the regions through the influence of his family. Gwilym Teilo referred to Brychan Court in the parish of Llangadog as one of Brychan's seats, and Theophilus Jones claimed that the Lordship of Brycheiniog extended in olden times to Llandeilo Fawr and Llandybie.

......Dark and misty are the characters of this period, and time has gathered legends around their names, and the greater their piety, the more wonderful the tales about them. Yet, there is a grain of truth in many a fanciful legend, and, because of this, it is worth studying the lives of the saints in Wales. It was the local saint who established the early churches, and it was Brychan's name that was remembered in the church."St Tybie

"One of Brychan's daughters was Tybie, or Tybieu as it appears on old documents. S. Baring Gould states that she blossomed in the fifth century, and was killed by Irish pagans around the middle of that century. Her father held court at Court Brycheiniog, attached to Garngoch, a strong fortress on the edge of the Towy Valley. [The remains of Garngoch are still there today, just above Bethlehem]. Brychan was strongly opposed in his attempts to push his influence into Ystrad Towy and Glamorgan, and in a rebellion, Tybie was killed where Llandybie church now stands. Nearby is Gelli-forynion, where tradition has it that she and her sister Lluan and others lived in holy meditation. Their well is also nearby.

...... The story in Baring Gould and Fisher's standard book is somewhat similar; in this version, English or Irish rovers killed her. Mention is made of two traditions regarding the place of her martyrdom. One is where the present church stands, the other about half a mile away where a crystal spring gushed forth. In this book the sister's name is given as Lluan, and Llanlluan nearby is dedicated to her. Tybie had a cell on a meadow called Cae'r Groes (a farmhouse today, above the village).

...... Mention must be made of the tradition that the old church did not stand on the spot where the present church stands. The location of many of the old churches in Carmarthenshire was related to the religion that was in the country before the coming of Christianity; very often the church was raised within a circle of stones that were regarded for some obscure reason as sacred. In some old churches, the stones forming the circle can still be seen in the walls of the churchyard, and it was common to have circular churchyards – Bettws churchyard is round, and so was Llandybie before it was extended."The original church has long since disappeared, as the Celtic Christian churches were made of wood. The beautiful stone church that stands in Llandybie today is medieval in origin. Its tower dominates the village and is visible for miles around although the clock wasn't added until 1920. There were, however, bells in the tower from early on – there is a mention in the fifteenth century of "3 bells great and small". The nave, chancel, tower and roof timbers are 13-14th century. Wales was finally subdued by Edward I in the 13th century and Llandybie, its church and its lands, were then passed around a bewildering number of Barons.

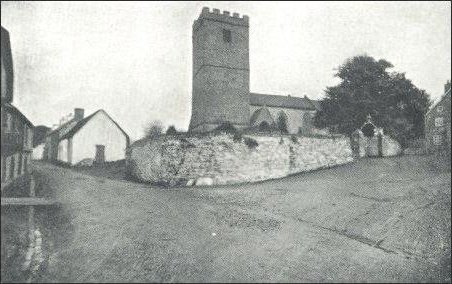

Llandybie church in 1900 – notice there are no cars and no clock, which wasn't added until 1920 as a war memorial to the dead of World War One. Edward I finally subdued Wales from 1282-84 but he didn't waste any time once he and his troops were here. In 1288 Edward acquired the tithes (taxes) of Llandybie and other parishes for a period of six years towards paying the cost of a crusade to Palestine. Tithes were church taxes levied at 10% on all people in the parish. They were paid in either money or produce and provided the money for the upkeep of the church and its duties towards the parish. As these included poor relief and tending of the sick, as well as the salary of the vicar and curates, this would have left Llandybie parish with nothing to provide for them.

It is in this period that we have the first recorded mention of Llandybie church, which can be found in the "Calendar of Chartered Rolls" (ii 275). On the 10th June in the 12th year of his reign [1284] Edward I granted Thomas, Bishop of St David's, permission to appoint a priest to "Llandegau".

Contents 1 Introduction 2 St Tybie 3 Oliver Cromwell slept here? 4 Llandybie and the Napoleonic wars 5 CADW Survey of 1966 3. Oliver Cromwell slept here?

The medieval fortified tower that is part of the church was not there for appearance's sake, as various wars and skirmished have affected the area over the centuries, the most recent being the Wars of the Roses and the 17th Century Civil War – another local legend is that Oliver Cromwell stayed in Derwydd mansion, though the area was Royalist in its sympathies. He is also reputed to have stayed at the Plas (Mansion) in Llandybie, a 17th century manor house only demolished as recently as 1967. As no written record exists for these claims they will have to remain as misty as only legends can be, although Cromwell was in Wales in 1648, the year he took Tenby Castle. Sir Henry Vaughan, owner of Golden Grove, just five miles from Llandybie, fought on the Royalist side and was imprisoned in the Tower of London, and his two sons were imprisoned at Tenby castle, so there are plenty of local connections to Cromwell.

The uncertainties of the middle ages in the Llandybie area came to a head during the Wars of the Roses at Carreg Cennen castle and after the Yorkist victory in 1461, the castle was deemed too much of a threat to the monarchy and its main fortifications were destroyed the following spring.

Contents 1 Introduction 2 St Tybie 3 Oliver Cromwell slept here? 4 Llandybie and the Napoleonic wars 5 CADW Survey of 1966 4. Llandybie and the Napoleonic wars

Stability eventually came to the area after the final resolution of the Civil War and the restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660. Since then the local gentry families have been responsible for various alterations to the church, as the CADW survey below details, with a major restoration in the Victorian period. The changes since then have thus owed more to changing architectural fashions rather than military demands. Much of the restoration of Llandybie church in the middle of the nineteenth century was paid for by one of the gentry families of Llandybie, the DuBuissons of Glynhir. There is much romance attached to this family and not a few legends as well – hiding agents of Napoleon in their cellars or making a fortune out of the Battle of Waterloo being among them, so a digression may be in order.

The DuBuissons were a French Huguenot (Protestant) family who came to Britain to flee the persecution of Protestants that ensued in France after the "Edict of Nantes" was revoked in 1685. The Edict was a decree by which Henry IV of France granted the Protestant Huguenots freedom of religious worship in 1598. Louis the Fourteenth revoked this in 1685 and attempted their forcibly conversion to Catholicism with the result that 400,000 Protestants fled from France, 40,000 settling in Britain.

The first member of the DuBuisson family to settle in this country was Peter Groteste DuBuisson; he lived in St George's Hanover Square, London, and according to the family records became a citizen of this country in 1706. About 1770 his son, also Peter, settled in Llandybie and bought Glynhir from a local gentry family, the Powells, for £3,000. We'll let Gomer Roberts take up the story at this point (Hanes Plwyf Llandybie, p40):

Messages by Pigeon Post

"Perhaps this may be the best place to deal with the legend in the parish that the family betrayed this country during the Napoleonic wars. The people claimed that this was the purpose of the big dove-cot in Glyn-hir – to keep pigeons to carry French spy messages. The truth is, the present dovecot was not built until after the battle of Waterloo, and the previous one was a small wooden dovecot Apart from this, it was quite common in those days for the houses of the gentry to have dove-cots, and for a good enough reason, and that was to add to the food of the family."Gomer Roberts may be mistaken about the age of the dove-cote at Glynhir which he claims "was not built until after the battle of Waterloo". The Welsh ancient monument organsation CADW surveyed Glynhir Mansion, including its dovecote, in 1951 and again in 1999, when its findings were in favour of an 18th century construction for the dovecote:

"Probably late C18, put up as one of the improvements following the acquisition of Glynhir by Peter DuBuisson in 1770. Until recently the dovecote was surmounted by an octagonal pyramid roof with a wooden cupola, and retained the complete potence. According to a strong local tradition, the first news of the victory at Waterloo came to Britain by pigeons returning to this dovecote; Caroline DuBuisson is said to have raced to London and to her connections, the Rothschild family, with the news, to take maximum commercial advantage of this early information." (CADW record number 10,904)

Glynhir House as it is today with the nearby waterfall in the middle. It was the home of the DuBuisson family from 1770 until 1921. Glynhir seems to have attracted legends around it, perhaps because of the exotic origins of the DuBuissons:

Secret cellar for spies and weapons?

"Another legend is of a secret cellar at Glyn-hir and the Western Mail in the 1930s gave quite a romantic opinion about it. "It can only be conjectured that such a place must have been constructed and used for the hiding probably of French spies or the concealment of contraband and weapons of war." The cellar, however, was not a very secret place, but was used for the ordinary purpose of keeping 'game' after a hunt. Apparently it did not occur to anyone to find out when the cellar was built. Of course, it was quite natural for this story to obtain a footing, because they were a French family, but it is certain that the local inhabitants would not have forgiven them if they were guilty of betrayal in time of war. To the contrary, the family were very popular in Llandybie over the years, and as to the rumour of hidden weapons, it is more than likely that neither the knife works in Glyn-hir or the forge at Llandyfan were working at the beginning of the last century."But the most enduring story of all is how Caroline DuBuisson made her fortune by profiteering after the Battle of Waterloo. Gomer Roberts again:

"By all accounts, Caroline DuBuisson was a woman with a very strong personality, and had a keen eye to making money. She will always be remembered for one occasion with regard to this. The circumstances are uncertain, whether it was the time of Napoleon's escape from Elba, or the time of his defeat at Waterloo. Anyway, when Napoleon escaped, it happened that two young men related to the family were staying at Glyn-hir, and they were immediately recalled to the army to proceed to France. They left at once, taking with them several pigeons, and after the battle of Waterloo, these pigeons brought the news to Glyn-hir of Napoleon's defeat. In London at that time there was a rumour circulating that things had gone the other way, with the result that the market fell. Caroline DuBuisson rode all the way to Bristol, and from there to London, and bought as many 'Consols' as she could lay her hands on. Within a few days, London heard the true news, but by this time Mrs DuBuisson had made a fortune."

The house and its extensive estate remained in the possession of the DuBuisson family until sold by them in 1921. Since then the estate has had several owners, with the present ones being in possession since 1965, and who have undertaken extensive – and much needed – resoration work. It is currently a hotel and in addition to the usual accommodation, offers courses and activities on painting, outside photography, creative writing, arts and crafts plus golfing breaks. The present owners have a web site with a brief history of the mansion and some photographs on: www.theglynhirestate.com.

Contents 1 Introduction 2 St Tybie 3 Oliver Cromwell slept here? 4 Llandybie and the Napoleonic wars 5 CADW Survey of 1966 5. CADW Survey of 1966

Perhaps the age and history of Llandybie church should be left to the Welsh ancient monument organization CADW who surveyed the building in 1966 (Cadw is Welsh for 'to keep'). Their report contains highly technical architectural language but is worth reprinting nonetheless:

Authority: Carmarthenshire; Grade: II

Date Listed: 08/07/1966; Date Amended: 27/08/1999

Community: Llandybie

Locality: Llandybie village; Grid Ref: 26182 21554

Record No: 10915

Name of Church: St. TybieLocation

At the centre of Llandybie village. Large stone-walled graveyard to north side (recent parts walled in concrete blocks). High wall with steps and iron gates from the street at west and south; stile beside south gate. Church House at south-east.

History

The church stands in what was conspicuously a round churchyard, the line of which is still traceable as a change of level within the present much-enlarged churchyard. The nave and chancel are evidently the historic core of the church, perhaps C13-C14; the axis of the chancel is slightly inclined to the left. To these a fine medieval tower, a south aisle and a Lady-chapel have been added, the latter not following the inclination of the chancel. A ceiling appears to have been formed directly to the underside of the medieval roof timbers c.1700. Windows described by the Victorian restorers as 'pagan monstrosities' and a west gallery were also inserted. A school is known to have been held in the gallery from 1786. Restoration of the church was undertaken in the mid-C19 under the leadership, and largely at the expense, of Mrs Caroline DuBuisson of Glynhir, and mainly during the incumbency of the Rev Lewis Morgan. The windows were first to be restored, c1852. The ceiling and gallery were removed c1861. The main restoration was carried out by [Sir] George Gilbert Scott, c1856, but some work was done by John Harries, architect, of Llandeilo. The pews throughout were renewed, the floor throughout repaved and the timbering of the roofs restored. The main focus of the restoration was the chancel, with very good joinery in the reredos, side screen, altar rails and choir pews. The reredos, side screen and altar rails are said to have been brought from London. The tower clock was installed in 1920 by Joyce and Company, as a war memorial.Exterior

Nave and chancel to the north, with aisle and Lady chapel to the south, all much restored; fine large south-west tower. C19 vestry to south, porches to south and west and small boiler-room at north: all in local axe-dressed gritstone, informally mixed in places with limestone. The tower, the north wall of the present chancel and the walls of the C19 vestry are strongly battered at foot. All the doors and windows in the body of the church are dressed in oolitic limestone. Roofs of local gritstone slabs, except for a hidden slope roofed in slates; restored coped gables in oolitic limestone with finials. The tower is of three stages. Higher stair turret at the north west corner. Crenellated parapets slightly cantilevered forward above a weathered and undercut string course. Carved human face at the centre of this string at north and another at south. Double belfry-openings on all faces, with Tudor heads; partly restored. String course at the base of the belfry stage also weathered and undercut, another larger string course at the top of the battered base. Tudor two-light window in the west side above the lower string course, small round-headed window to the south; slit lights to the stairs. Clock faces to south, west and east. Two gargoyles on the west face are restored. The windows in the body of the church are mostly restored in Decorated style. At east is a two-light window to the Lady chapel with trefoils in the head tracery; a three light window to the chancel with quatrefoils in the head tracery. Both have label moulds on floral stops and relieving arches over. To north and south of the nave and aisle are two-light windows with quatrefoils in the tracery heads and label moulds on floral stops. Similar window to the south of the aisle but without a label. Three-light window to south of the C19 south vestry, in plate tracery; two-light Tudor style window to the east; Caernarfon-arched doorway at west. The west and south porches are open-fronted with pointed and chamfered arches. Ornate ironwork to the west door.Interior

The C19 restoration has produced an interior of uniform appearance apart from the chancel, which stands out for its joinery and monuments. Arcade of two equilateral-pointed chamfered arches and one high level irregular arch (altered 1971) of segmental form. Two similar pointed arches separate the chancel and Lady chapel (or Ladies' Choir). Wide and tall chancel arch, also chamfered. The arches lack caps or mouldings at the imposts. Similar arch (irregularly formed) from aisle to Lady chapel. Nave and aisle pewed as one, in three blocks; similar pews facing towards the chancel in the Lady chapel. The nave, chancel, aisle and chapel are all roofed with trussed rafters braced to a barrel form. Although much restored, some of the timbers are moulded and appear to be medieval Black and red quarry tile flooring throughout, in chequer pattern. High boarded dado against the nave west wall only. Timber pulpit on a stone plinth at the left of the chancel arch. One step up to the chancel. Two choirstalls each side, the desks of the boys' stalls removed (1995). Carved Gothic altar rails, of Scott's restoration, with moulded top and foot rails and cinquefoil-headed openings. Reredos with four panels, each with a four-centred head, with painted verses on metal. Carved screen at right, in Perpendicular style with traceried heads to the openings and a carved cresting. The organ has been installed at high level in the first arch of the chancel arcade, with its console and bellows in the Lady chapel. To its left, in the chancel, is a cast-iron Royal Coat of Arms, said to have been cast at Coalbrookdale, 1817. Glass mostly a pattern of fleur-de-lys quarries with coloured margins. Only the east window is pictorial. It shows four scenes from the New Testament: the Nativity, Presentation, Crucifixion and Ascension; undated. Two fonts: a simple stone font of hexagonal shape, with a hexagonal shaft and base, perhaps pre-Norman; modern cover. The second is square in Early English style, Bath stone, probably contemporary with the restoration of the church; cover donated in 1936.Memorials

Elizabeth Bridgstock of Llechdonny, 1667: an eared-framed panel beneath a round pediment crowned by arms on a cartouche, and supported by a cherub on a bracket, in the Lady chapel. Beside this is the hatchment of Sir Henry Vaughan, d1676, the oldest hatchment in any church in south Wales. A fine collection of two Baroque and five Georgian memorials at the north side of the chancel. Nearest the chancel arch is a monument of 1703 to Thomas Bennett of Aberlash, with two fluted pilasters and large pilaster-cornices; a pediment formed of ramped scrolls. Second from the east wall is the monument to Sir Henry Vaughan, 1676, the colouring of which has recently been carefully restored (by E. Williams). This has a high relief bust, repaired; the figure, in a niche, holds a dagger and sword and is surrounded by objects of symbolic significance. Twisted columns and broken pediment; on the frieze 'Vivit post funera virtus'. At top is a cartouche with helmet. At each side are putti with trumpets, resting on skulls. Inscription beneath, with side volutes and a cherub beneath on a bracket. The Georgian monuments include two sculpted by T King of Bath: to Rebecca Lewis of Llanllear, 1782, a draped urn; to Bridget Jones of Duffryn, 1780, an undraped urn on a shelf. The others are one to Arthur Price, 1757, a draped urn on a pedestal; to Elizabeth Vaughan, 1754, a plain urn in a broken pediment and to Elizabeth, Lady Stepney, 1795; a draped urn on a sarcophagus with ramped scrolls; the shelf on architraveless fluted columns each side of the inscription. Low relief figures on the sarcophagus. C20 brass memorials beneath.The memorials of the DuBuisson (and Henckell) family are all plain inscribed tablets, in a group in the southwest corner of the nave. These range in date from 1772 to 1930. Memorials to the north of the nave include one to Eliza Maria Williams, 1878, with short black colonnetes, oolitic limestone caps, bases and shelf, and a steep Gothic stilted pediment surmounted by a cross; one to Hester Williams, 1837, in sarcophagus form, by H Wood of Bristol. To the right of the chancel arch is a brass memorial to the fallen of the Great War, and another to the fallen of the Second World War in the south aisle. There is also a marble memorial to members of Capel Wesle fallen in the Great War, brought here when the chapel closed in 1973. Plain inscribed memorials in the west porch include one to Mary Davies, 1759, by John Thomas of Llandybie; another to J E Protheroe, surgeon, 1836, also signed John Thomas of Llandybie.

Listed

Listed at grade II* as a medieval church with a particularly fine tower, C19 interior and many fine monuments.Reference

G Roberts, Hanes Plwyf Llandybie (1939) pp. 60-79;

B Thomas, Llandybie Parish Church, History and Guide (1970);

RCAHM: Carmarthenshire (1917) p.103;

Llandybie Parish Church Inventory;

Dyfed Archaeol. Trust SMR PRNs 824, 10300.

Contents 1 Introduction 2 St Tybie 3 Oliver Cromwell slept here? 4 Llandybie and the Napoleonic wars 5 CADW Survey of 1966