AMMANFORD

PARK MEMORIAL GATES

AND CENOTAPH

(scroll

down for a brief history of the gates)

(Click HERE for a

history of Ammanford Park)

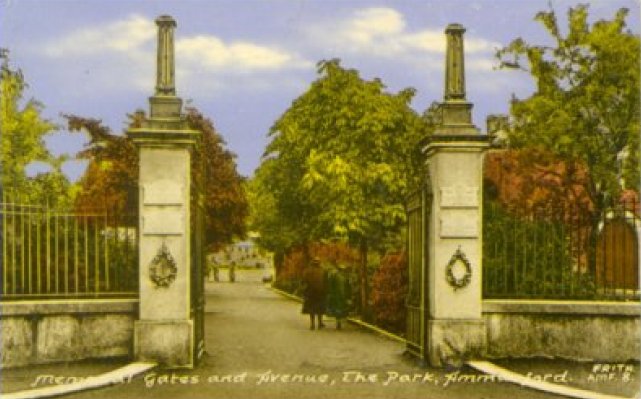

The entrance to Ammanford Park in Iscennen Road is through a set of Memorial Gates, erected in 1937 in honour of the fallen of the First World War, 1914-1918. With one of those ironies that only history can provide, within two years the gates would be forced to commemorate the fallen of a second world conflagration between 1939 and 1945. The Memorial Gates are Ammanford's 'Cenotaph', the scene of a wreath-laying ceremony each anniversary of the Armistice on November 11th 1918 which signalled the end of World War I. Today, the right-hand pillar of the gates lists all those from Ammanford who fell in the First World war (91 in all) and the left-hand pillar lists the town's 42 dead from World War II. The gates cost £100 to erect in 1937, the year of the very first wreath-laying ceremony which took place on Armistice Day, November 7th. The tree-lined avenue leading from the gates is called 'Memorial Avenue', though initially it was to be called 'Coronation Avenue'. (Two events are candidates for this name: the planned coronation of Edward VIII, cancelled when he abdicated due to his involvement with American divorcée Mrs. Simpson, or the actual coronation later the same year of his brother as George VI). On the recommendation of tree surgeons some of the trees were cut down the 1990s but new saplings were planted in their place and are already beginning to blossom forth into sturdy trees for the benefit of future generations. The Memorial Gates are listed as Grade II by the Welsh Historic Monuments organisation, CADW.

Ammanford Park Memorial Gates today, adorned with wreaths from the Armistice Day ceremony and with the names of the dead from two World Ward engraved on the pillars

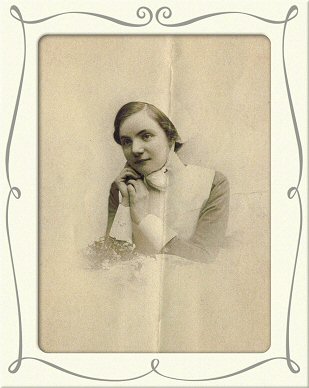

Those then are the bare facts about the gates, not much of a story in itself, were it not for those 133 names inscribed on the pillars. To most of us now living in Ammanford they sadly mean nothing to us personally. Yet each one was once a member of a family; each one, as well as a soldier, was someone's son, father, brother, husband, boyfriend, workmate, neighbour, friend or, in one case, someone's daughter and sister. For there is one name inscribed on the First World War pillar which stands out from all the others. It is to this name, Emma Fletcher, we now turn and in the process glimpse how those terrible war years affected just one Ammanford family. While each and every one of those 133 names has their own story to tell, the Fletcher family, for now, will have to substitute for them all. In World War I alone twenty million people world-wide lost their lives, most defending some mud-filled, rat-infested trench on the Western and Russian Fronts, millions of men who were sent to "gain a little patch of ground/That hath no profit in it but the name." (Hamlet, Act IV, scene iv.) No profit at all except for the world's arms manufacturers, perhaps. Probably forty million died in the Second World War, doubling the efficiency of the human killing machine in just one generation.

The FLETCHER family

Mr and Mrs Tom Fletcher ran a newsagents business at 27, College Street Ammanford. During the First World War five of their children enlisted; they were:388072 Sapper Charles Isgar Fletcher, 5th Field Company (Royal Mons) R. E.

Nurse Emma Grace Fletcher, Griffithstown Military Hospital, Pontypool

Gunner Archie Fletcher, Royal Garrison Artillery

Private Bernard Fletcher

Private Myrddyn FletcherWhat we now call the First World War (though was then called the Great War) ended at 11am on 11th November 1918. On the 3rd of November 1918 (just 8 days before war ended) the Fletcher family received the sad news that Sapper Charles Fletcher, serving in France, had died on the 30th October in a military hospital near Calais of double pneumonia. He was buried in the Terlincthun British Cemetery, Pas de Calais. Sapper Fletcher, a married man who lived with his wife in Monmouth, had served for two years in Egypt prior to a posting to France. Sapper Fletcher, 25 years old, was formerly employed on the staff of the Amman Valley Chronicle. Then, shortly after this tragic news, further gloom was cast over the family when they were informed, on the 14th of November 1918, that their other son, Gunner Archie Fletcher, had been wounded and was in a military hospital in this country (fortunately he recovered fully).

Their daughter, Emma Grace, returned home to console her parents from Griffithtown military hospital, Pontypool, in which she nursed wounded and sick soldiers. However, tragedy was to deal yet another blow to an already devastated family. Shortly after returning to her duties, Nurse Emma Grace Fletcher fell victim herself to the virulent strain of influenza known subsequently as Spanish Flu which was then raging throughout Britain, Europe, North America, Africa, India and Australasia. She died suddenly on Tuesday the 19th of November 1918 aged 28 years.

Spanish Flu seven days after war ended.Nurse Fletcher was a very popular nurse at Griffithtown military hospital, and this was borne out at her funeral. Before the body was transferred to Ammanford for burial the coffin was laid out in the hospital for viewing. There was a touching scene before the closing of the coffin when several hundred wounded soldiers, many of whom had been nursed by 'Gracie', as she had been known, passed by to pay their last respects. An impressive service was held in the large hall of the hospital where the coffin, draped with a Union Jack flag, and with a floral wreath in the shape of a broken harp given by the staff and patients, was surrounded by all the staff and able-bodied patients. The vicar of Griffithtown along with the hospital chaplain and the Rev Rhys Davies, English Baptist Church, conducted the service.

Following the service, over 230 soldier-patients escorted the coffin to the railway station for transference to Ammanford for interment. The six bearers who carried the coffin the mile and a half to the station were also patients from her ward, followed by Nurse Fletcher's parents and friends from Griffithtown. The matron, sisters and staff, many of whom pushed patients in chairs and assisted soldiers on crutches, made up the cortege.

Nurse Fletcher's body arrived by train at Ammanford Station at 5.30 pm on Friday the 22nd of November 1918. The following day, Saturday the 23rd, the funeral took place at 3.30 pm in St Michael's Church burial ground. A large congregation gathered, fully representing the whole community, and Ammanford effectively closed down for the rest of the day. The Rev W E Thomas, minister of the English Wesleyan Church, the family's place of worship, officiated at a short service in the house and the Wesleyan Chapel; He was assisted by Rev T E A Harries, and Mr George Thomas, Betws, played the organ. Whilst Ammanford fell silent to mourn her loss, a memorial service was being held at St Hilda's Church, Griffithtown, simultaneously.

[Thanks are gratefully acknowledged to Ken Burton of Ammanford for the above information about the Fletcher family.]

Carmarthenshire Roll of Honour website

Ammanford's park gates list the names of the fallen but give no further details. Now, thanks to a recent website, stories can be put to some of those names. Click on Carmarthenshire Roll of Honour and keep scrolling down for brief biographies, most of which are accompanied with photographs of their gravestones.The Spanish Flu – healthy one minute, deathly sick the next

It wasn't on the battlefields of France that 'Our Gracie', Nurse Fletcher, died but in a Welsh Military Hospital where she succumbed to a killer more deadly than all the bullets, bombs and gas of the battlefields – Spanish Flu. She is thought to have contracted the virus from one of the soldiers she tended, who himself had brought it from the killing fields of France. As we saw above, her brother too had been struck down by the same invisible killer in a military hospital in Calais. The 1918 Spanish flu epidemic killed more people in just a few months than four years of all-out, world-wide slaughter had managed to do, and when it struck, it struck with devastating quickness, as this children's poem from the period hints:I had a little bird,

Its name was Enza.

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.In 1918, even small children would sing about the sickness that devastated daily life across the world. The song is reminiscent of the children's rhyme that arose in response to the so-called Black Death of the Bubonic plague in the 1300s:

Ring a ring of roses,

A pocketful of posies,

Atishoo, atishoo

We all fall down.By the autumn of 1918 the world had struggled through four years of terrible warfare. But after the Armistice on 11th November 1918 it was over, the threat was removed, and mankind was safe again. Or so they thought. But in the middle of 1918 a new killer was silently spreading its way through people's lives. It started out as a simple case of the flu. But it worsened, until it became deadly. It would do its work with lethal efficiency. It struck with amazing speed; often killing the victim within hours of contracting the disease. So fast did the 1918 strain overwhelm the body's natural defences, that the usual cause of death in influenza patients – a secondary infection of lethal pneumonia – oftentimes never had a chance to establish itself. The virus would cause the body to haemorrhage, the lungs would fill with liquid and the patient would drown in their own fluids.

A strain of influenza seemingly no different from that of previous years had suddenly turned so deadly, and engendered such a state of panic and chaos in communities across the globe, that many people believed the world was coming to an end. Not only was the Spanish Flu strikingly virulent, but it displayed an unusual preference in its choice of victims – tending to select young healthy adults over those with weakened immune systems, as in the very young, the very old, and the infirm. The normal age distribution for flu mortality was completely reversed, and had the effect of gouging from society's infrastructure the bulk of those responsible for its day to day maintenance. No wonder people thought the social order was breaking down. It very nearly did.

At the close of the First World War, when Spanish Flu appeared, the world was a very different place from today. Although the cockpit of the war was in Europe and the Middle East, nations from all over the world sent troops to the conflict. They came from the USA and Canada, from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, European and Asian Russia, the Indian sub-continent, the Far East as far as Japan, and the African nations who were then European colonies. That conflict, initially called the 'Great War' truly deserved the name of the First World War it acquired later. The massive troop and civilian movements all over the world meant the deadly virus was carried back to almost every corner of the earth when the troops went home from the killing fields of Europe.

During the period from autumn 1918 to spring 1919, the mortality figure for the full pandemic worldwide is believed to stand somewhere between 30 to 40 million. In India, the Spanish Flu is thought to have culled more than 10 million from the population.

It's now thought that the Spanish Flu actually originated in Tibet in 1917, though the USA is another source sometimes given. As the armies of various nations moved across the continents the flu spread with them. Before long cases were showing up in Europe but the reasons behind its beginnings and final end are still a matter of study. The name of Spanish influenza appears to have stuck after the virus struck early and with great killing efficiency in Spain. The epidemic, known as a pandemic because it grew to worldwide proportions, appeared as early as March 1917 in the USA, when soldiers at Fort Riley, Kansas, burned tons of manure, spreading the deadly virus on the winds.

After establishing a stronghold in France, the flu moved into Spain. Spain was a neutral player in the First World War and for that reason it had no need to censor knowledge of the illness from its people in order to keep them focused on the war effort. The Spanish press then fully documented the illness, along with its terrible life-taking effects on the human body. The fever would affect a person in the following way:

1 High fevers, shivers, coughs, muscular pain and sore throat. 2 Tiredness and dizzy spells. 3 Loss of strength to the point of not being able to eat or drink without assistance. 4 Difficulty in breathing. 5 Death. The epidemic spread quickly around the earth. In all, some 525 million people were infected by the virus, with estimates for the number of people dying ranging from 30 million to 40 million. That was more than twice the number who had been killed during the Great War. In the United States, estimates place the death toll at 500,000 to more than 675,000. As a comparison, fewer than 125,000 Americans lost their lives serving in the armed forces during World War One. Then, as quickly as the Spanish Flu came to plague mankind it disappeared. It briefly reappeared in March, 1919. This time, however, the world was better prepared and the virus was able to be quarantined. Again it disappeared after inflicting a rapid death toll. The world was glad to see the back of it.

Spanish Flu – could it return?

As a new millennium dawned it brought with it serious new concerns for the medical and political worlds to address. Scientists became increasingly jumpy at the threat posed by a new strain of influenza carried by birds, wild and domestic species alike. Known popularly as avian or bird flu, medical science began to take the virus seriously when it jumped species and started killing humans as well as birds. Remorselessly, it began moving westwards from the far east and into Europe. The worry increased when modern techniques of DNA analysis began detecting links between the new virus and the virus responsible for the Spanish Flu ninety years before, as the following extract from the website of the American Public Broadcast Service explains:Using tiny pieces of preserved lung tissue and a body frozen in the Alaska tundra, a team of scientists were able to recreate the 1918 Spanish flu virus, an achievement that may help uncover how the current deadly strain of bird flu could become transmittable between humans.

....The results, published in the journal Nature in October 2005, offered some parallels between the Spanish flu virus and the H5N1 strain of the bird flu slowly spreading through Asia and recently turning up in other parts of the world.

.....By late October 2005, the bird flu, which can be transmitted from birds to humans, had killed 60 people, mostly in Vietnam. Evidence of the disease also has been discovered in birds in other countries, including Croatia, Turkey, Romania, Russia and Greece.

....Four of the eight genes in the H5N1 strain contain mutations seen in the deadly Spanish flu 87 years ago, according to the published reports.

....At the time of the Spanish Flu, microbiologists didn't know what caused the widespread deaths; the influenza virus was not identified until 1933. And, as the Washington Post reported, although biologists later were able to determine the broad family of influenza viruses the 1918 strain came from, its genetic identity was lost.

....That is, until Jeffrey Taubenberger, a molecular pathologist at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Rockville, Md., and his team toiled for 10 years to piece together the deadly virus in a high-security laboratory at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

....They got their samples from small pieces of lung tissue, preserved in wax after the autopsies of two soldiers among the Spanish flu's 675,000 American victims, and from the frozen body of an Inuit woman who died from the virus in November 1918 and was buried in the Alaska permafrost.

....The virus's eight gene segments, or strands of RNA, were in fragments, but the team was able to piece them back together using gene sequencing and polymerase chain reaction -- a method of creating copies of specific fragments of DNA.

....Analysis of all eight genes showed the Spanish flu came directly from a bird virus and moved into humans after slowly mutating. The analysis suggests that H5N1 also might be capable of spreading between humans through gradual mutations, reported the Washington Post.Source: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/health/birdflu/1918flu.html

And, as if to reassure us all, the website concludes by telling us that: "Scientists hope to use the information gleaned from reconstructing the Spanish flu to create new vaccines and treatments." It's not just the scientists who hope they can.