PWLL PERKINS

THE AMMAN VALLEY'S

WORSE MINING DISASTERHere is a list of the ten worse accidents in British mining history, arranged in descending order of fatalities:

YEAR DATE PIT COUNTY 1913 14th October Universal Pit, Senghennydd Glamorgan 1866 12th December Oaks Colliery, Barnsley Yorkshire 1910 21st December Number 3 Bank Pit, Hulton Lancashire 1894 25th June Albion Colliery, Cilfynydd Glamorgan 1934 22nd September Gresford Denbighshire 1888 11th September Abercarn Colliery Monmouthshire 1877 22nd October Blantyre Lanarkshire 1862 16th January New Hartley Northumberland 1857 19th February Lundhill Yorkshire 1869 8th December Ferndale Glamorgan It might be worth observing that half the above collieries were in Wales, which has only five percent of the population of Britain. Also, all the above disasters except one happened in the autumn/winter period.

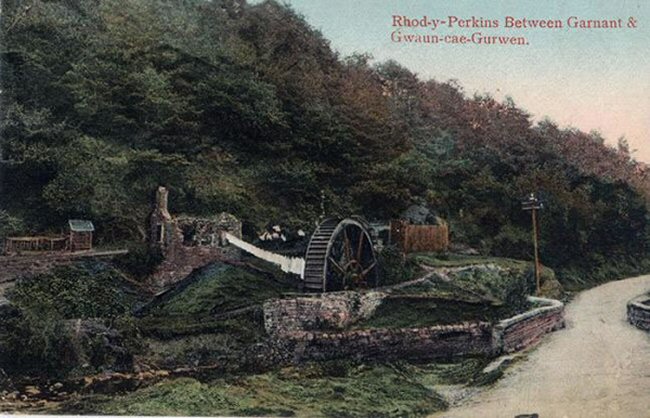

The site of the worse mining disaster in the Amman Valley. Rhod y Perkins (Perkins' Wheel), Garnant Colliery, which produced the mine's power. The colliery, which was on the border between Garnant and Gwaun Cae Gurwen, was demolishd long ago and no trace now remains.

In comparison, the ten men and boys killed in the Amman Valley's worse mining accident falls mercifully short of these horrific figures, but it was still ten deaths too many. The date was 16th January 1884 and a serious accident occurred at Garnant Colliery, also known as 'Pwll Perkins', when ten men going down to work met their death. The first five trips of forty men had been lowered safely but it was the next trip that proved fatal to those ten unfortunate miners. Normally not more than eight men were allowed to descend in the cage at one time, but on this morning ten men crowded into the cage on its fatal trip. They hadn't gone down many yards when the wire rope to attached to the cage snapped, and it plunged to the bottom of the shaft 225 feet below.A fellow miner was charged with manslaughter for causing the deaths of the ten men; for being a trespasser; and committing an illegal act by unauthorised operation of the keeps (the keeps support the cage at the top of the pit). On Saturday the 2nd February 1884 he appeared at Llandeilo petty-sessions charged with these offences but was acquitted of all them. Particularly ludicrous was the charge of trespass – the miner was actually working at the colliery when the accident happened so could hardly have been trespassing. More worrying, but predictable, the mine owners themselves went unpunished. It also emerged that there were no death benefits for the victims' families as their fund only covered sickness. One reporting newspaper (Carmarthen Journal) printed a request for donations to help ease the inevitable hardship facing the families of the dead men.

Here in more detail is the story of the events that led to this terrible disaster, taken from a website designed by the great-great grandson of one of the men killed. This well-researched project provides details of the inquests and court case which followed the deaths, along with several contemporary newspaper reports of the whole affair.

What Happened That Morning?

The men started work at around 4 am that January morning so that they could finish their shift early. The miners, nearly a hundred men, wished to attend the funeral of the young wife of one of their colleagues. It was an especially sad occasion as the young couple had not long been married.

....The cage made five journeys that morning, carrying a total of about thirty men down to the bottom of the shaft. On the sixth trip, the cage successfully delivered a man and a horse, the total weight of which would have exceeded the weight of eight men which was the designated maximum cargo. This is merely academic, as the rope, which was supposedly of the highest standard, was calculated to withstand a working strain of 5 tons and a breaking strain of 45 tons!

....On what was to be the seventh descent ten men crowded into the lift. Two of the boys pulled an old man out of his place in order to crowd themselves in. Despite this extra weight, given the statistics provided by the rope manufacturers, the total pressure on the rope should still have been well within the parameters of the rope's capabilities.

....Part of the morning safety routines at the mine included the checking of the rope by the fitter/mechanical engineer. He would do this by running the rope, which was 140 yards long, through his hand to check for any frays. This procedure was apparently carried out the previous morning. The rope, consisting of 12 steel wires wrapped around a hemp cord, was relatively new, having been installed on September 18th 1882, approximately 16 months previously.

....The engine room man and the trained banksman would work together. The banksman would pull the lever to retract the fangs of the keeps, therefore allowing the cage to descend into the shaft. The engineroom man would then work the machinery which lowered the cage.

....There was, however, a problem with the fangs on one side of the keeps which did not always open fully. A horse door had been fitted to one side of the cage and since then it was not uncommon for one set of fangs to catch on the door hinge and scrape against the side of the door. This did not happen on every occasion but would certainly occur if the lever was not pulled hard enough to open both sets of fangs fully.

....This is something the men were said to regard as dangerous but none of them ever refused to go down in the cage.

....On this terrible morning the trained banksman was elsewhere. He was lowering men down in a second cage, which was prohibited for the use of carrying men. The person operating the keeps of the main cage was not a trained banksman and although he was not officially authorised to carry out this duty, it was not uncommon for untrained miners to do this.

....As the cage started its descent it had only travelled two or three yards when the rope broke, approximately 17 yards from the top of the cage. The cage, with ten men inside, plummeted to the bottom of the 225 feet deep pit and landed with an awful thud, killing all of the passengers outright.The Events That Followed

We shall never know the whole truth of what happened. The opinion of the government inspector of mines (the only independent witness) is that steam and gases emanating from the pit had corroded and therefore weakened the rope at the point of fracture. Did the fitter miss the fact that the rope had narrowed and corroded at what was to be the fracture, due to there being grease on the rope?

....The mining company wasted no time in finding someone to blame once it was disclosed that, at the time of the accident, the keeps were being operated by a collier and not the trained banksman. This collier was arrested and had to endure a trial for manslaughter before being acquitted. They claimed that he had been tampering with the lever, thus causing a jolt on the rope when the cage caught on the fangs of the keeps. Other colliers testified that many others had worked the keeps when the banksman was not there.

....According to an article in the "Colliery Guardian" one man who worked at the colliery, named George Bartlett, gave evidence that he saw the cage stop when nearly out of sight and heard a grating sound. He said that he didn't think that the engine had stopped because the rope was going out.

....From the same newspaper article a man named Thomas Morgan stated that he could see the cage shaking and struggling in the mouth of the pit. He said that when the cage was set free the men screamed and there was a loud noise as the rope broke.

....The engineman claimed that if the cage had caught and the rope had run slack then when the slack had been taken up as the cage descended there would have been a loud noise in the machinery. He said that there had been no such noise.

....It transpired that the banksman who should have been working the keeps was elsewhere at the time of the accident and had been lowering men down in an unauthorised cage, which was not to be used for transporting men.

....The miners were unhappy that a horse door, which had been fitted to one side of the cage, would catch against one set of fangs of the keeps, which did not always recede fully. This fact was held back and not disclosed until near the end of the inquest. After the accident, the collar board was cut back to enable the fangs to recede further, though it was claimed that this was done only to satisfy the miners and had no safety value.

....Mr R.C. Fisher, an eminent mining engineer, who examined the site on the Saturday after the accident, collapsed and died while waiting for the train at Garnant Station. The cause of death is supposed to have been heart disease. This is yet another sad event associated with the Pwll Perkins disaster.[From http://www.cwmammanhistory.co.uk/Garnant_Colliery_Disaster/index.html]

The colliery was known locally as Pwll Perkins after the Perkins family who once owned it and whose company name was Perkins and Sons. These were the registered owners in 1869. The Carmarthen Journal reported that Garnant colliery had been idle for years but that work had restarted in 1874. It is worth noting, however, that the pit being worked in 1874 was on the opposite side of the river to the original pit and water wheel. By the time of the 1884 disaster, the colliery was owned by the Garnant Colliery Company, who had their office at Cambrian Way, Swansea. The Cambrian Newspaper reported that at the time of the accident, the colliery was being worked by David Pugh MP. By 1908, the registered colliery owner was the Cawdor and Garnant Collieries Ltd., Garnant. At this time, there were only 69 men working underground and 33 above ground. Site Closure Plans for the Garnant Colliery site were signed and dated by the colliery manager on 4th May 1914

The colliery owner, David Pugh MP, was also the Member of Parliament for Carmarthenshire, and it was he who was mainly instrumental in getting the Employers' Liability Act passed in parliament in 1880. He employed 150 men in getting coal at the colliery. [Source: The Cambrian, January 18, 1884.] When a fund was set up for the widows of the men killed Pugh donated £5. As the pound in 1884 was equivalent £92 in 2009 (Bank of England figure) this represented £460. That's £46 at 2009 prices for each one of the ten people killed, an insult if there ever was one. In contrast, to celebrate Queen Victoria's Jubillee in 1897, Pugh paid £500 to install a clock in Llandeilo church tower. With the pound in 1897 worth £97 in 2009 (Bank of England figure) that's equivalent to £48,000!

The names of the victims and their ages were recorded on the title page of an elegy composed in their memory. Three of the dead were only 14 years old. This was, and still is, the worse mining accident in the Amman Valley's history.

We reproduce, with an English translation made for this web site, the title page of that elegy, in which the incident is described, consolation offered and the dead named. As we read down the list, we may find ourselves pausing for thought, and dwelling on the tender ages of the last few named.

IN

Respectful Memory

OF

Those who met their end in a singularly

wretched way inGarnant Colliery, 'Pwll Perkins,'

CWMAMMAN,

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 16th, 1884

At about Four o'clock in the morning

Work had started sooner than usual that morning, so that the men could leave early to accompany the mortal remains of the wife of one of the workmen to her long home. The accident happened when the chain broke as the cage was starting down, and the ten men were sent hurtling to the other world.

........Their names, &c., David Roberts, Brynamman, 37 years old, married with five children. Thomas Bevan, Cwmamman, 23 years old, married with three children. William Lake, Cross Inn, 30 years old, married with three children. Thomas. Michael, Cwmamman, 26 years old, married. John Evan Jones, Cwmamman, 31 years old, single. John D. James, Cwmamman, 22 years old, single. Evan Roberts, Brynamman, 16 years old. Thomas Roberts, Brynamman, 14 years old, two brothers. Daniel Williams, Cwmamman, 14 years old. Edward Morgan, Brynamman, 14 years old.Printed by E. Rees, Ystalyfera

ER

Coffadwriaeth Barchus

AM

Y rhai a gyfarfyddasant a'u diwedd mewn modd hynod druenus, yn

Nglofa y Garnant, 'Pwll Perkins,'

CWMAMMAN,

DYDD MERCHER, IONAWR YR 16eg, 1884.

Oddeutu Pedwar o'r gloch y Boreu.

Yr oedd y Gwaith yn dechreu yn gynt nag arferol y boreu hwn, er gadael yn gynar i fyned i hebrwng gweddillion marwol anwyl briod un o'r gweithwyr, i dy ei hir gartref. Cymerodd y ddamwain le trwy i'r gadwyn dori pan oedd y Cage megys yn cychwvn i lawr, a hyrdd-iwyd y deg i arall fyd ar amrantiad.

........Eu henwau, &c., David Roberts, Brynamman, yn 37 mil. oed, priod a phump o blant. Thomas Bevan, Cwm-amman, yn 23 ml. oed, priod a thri o blant. William Lake, Cross Inn, yn 30 ml. oed, priod a thri o blant. Thomas. Michael, Cwmamman, yn 26 ml. oed, priod. John Evan Jones, Cwmamman, yn 31 ml. oed, sengl. John D. James, Cwmamman, yn 22 ml. oed, sengl. Evan Roberts, Brynamman, yn 16 ml. oed, Thomas Roberts, Brynamman, yn 14 ml. oed, dau frawd. Daniel Williams, Cwmamman, yn 14 ml. oed. Edward Morgan, Brynamman, yn 14 ml. oed.Argraffwyd gan E. Rees, Ystalyfera.

Tragedy, though grievous enough on its own, often enlists the aid of irony to deepen the wounds it inflicts. In attempting to finish work early to attend a funeral these ten men only hastened their own funerals instead. Their grieving relatives, like Shakespeare's King Lear, might well have had cause to cry out:

"Like flies to wanton boys, are we to the gods;

They kill us for their sport."(Shakespeare: King Lear, Act 4, scene 1, lines 36-37)

However appropriate such a world-view may be in the existentialist chaos of a Shakespearean tragedy, back in the real world, where cause and effect obey known laws, ropes do not snap by chance, or because of games played by bored gods, but from misuse by negligent mine owners, concerned only to maximise profits. If we were to substitute 'employers' for 'gods' in Lear's cry of pagan despair, though losing some of the poetry in the process, we can make better sense of what happened in 'Pwll Perkins' on that fateful day in 1884.

The Funeral Poem

Finally here is an English translation of the ode written for the funeral of the ten men. Naïve the poem may be, but the miniature portraits it offers of the ten dead miners are genuinely touching in their familiarity and sincerity.

PWLL Y GARNANT Eighteen hundred and eighty four

A year which will be long remembered

On the sixteenth day

Of the month of January, a heavy time.On the above very sad day

Ten men so warm and amiable

In Perkin's Pit in Cwmamman

Were thrown into eternal paradise.John Evans that sweet singer

In this so terrible event

Ending in an instant

Life in mid stream.aged 31 single John David James a pleasant boy

Who was much liked by all

I hope that today

He is in heaven without any pain.aged 22 single Thomas Michael my colleague

And my fit school pal

He also, I assume

Is in heavenly paradise too, with Godaged 26 married Dafydd Enoc a hard worker

Who was respected by all men

He also was hurled into eternity

Sadly and suddenly in this disaster.aged 37 maried Thomas Bevan another colleague

Who was so admired by me

Ready with his support

Always with a pleasant happy face.aged 23 married William Lake I did not know

But I hope that he

Arrived smoothly

At the pure heavenly abode.aged 30 married Edward Morgan the innocent lad

Much loved by his father

A flood of tears will accompany

The memory of this good young man.aged 14 Evan Roberts and his brother Thomas

Went together at the same time

From this accident we hope

They reach a pleasant place in paradise.aged 16 and 14 Daniel Rees a likeable lad

Who did not have a father or mother

Yet in the wife of Thomas Williams

He found a sweet sincere mother.aged 14 This accident has caused

Great mourning in Cwmamman

When we saw ten of our fellow workers

Suddenly tragically cut down.I hope that I can die

Completely naturally

I can bid farewell to my friends

Before I leave the world.We sometimes wish of you

Organisers of collieries of our country

That you will keep all machines

With good watchfulness.I am finalising by advising you

All you keen hard working colliers

For you to keep a careful

Watch on the rope.Now I'm giving you my name

In tender bright letters

David Aubrey Lewis

Is the author of this poem.

Date this page last updated: October 1, 2010