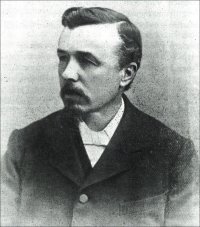

Watcyn Wyn as a young man Brynamman-born Watcyn Wyn came to Ammanford in 1880 and stayed until his death in 1905. By today, Watcyn Wyn is remembered chiefly as a hymnist, but in his day he was prominent in several fields. On the memorial plaque in Gwynfryn chapel, Ammanford, he is referred to as "Teacher, Poet, Preacher", and, to be sure, he made a contribution to the literary, educational and religious life of Wales during the last quarter of the 19th century. According to his biographer, the Revd Penar Griffiths: "He had an important and beloved place in the life of his country". In 1972, Ammanford miner and first-ever Secretary of State for Wales, Jim griffiths MP, said of him: "In my estimation Watcyn Wyn was the greatest man nurtured in the Amman Valley". (South Wales Guardian, June 22nd, 1972, page 6).

Watkin Hezekiah Williams was born on 7 March 1844 the son of Hezekiah Williams, of Cwmgarw Canal near the Gwter Fawr (Brynaman), and Anne Williams of Y Ddolgam near Cwmllynfell. He was born in Y Ddolgam while his mother was visiting her family, and W.W. liked to say that he was born when his mother was not at home. It was a remote, rural community that existed on the moorland at the foot of the Black Mountain. Consequently, many old rites and customs had survived. It is said that some customs were less agreeable than others. It seems that that the old custom of 'eating sins', i.e. the eating by the 'sin eater' of an offering of bread and salt placed on the coffin, had survived in the Amman Valley and the surrounding area until the beginning of the 19th century. This was a primitive rite and its purpose was to transfer the sins of the departed to the sin eater. But in his memoirs W.W. emphasizes the value of 'good neighbourliness' and speaks of customs like the cwrw bach (small, ie weak, beer) and the pice (Welsh cakes). When misfortune struck a family the neighbours would arrange to come together to give support to the unfortunates. According to W.W. the cwrw bach was a means of putting a poor man back on his feet and lifting his spirits.

By the middle of the 19th century the nature of the old society was changing. Roads and railways were developed, and the area came into contact with the wider world outside. Coal was already being worked and in 1847 the first two blast furnaces in the Gwter Fawr were opened. According to Enoch Rees, "This caused a great commotion in the area and the name of the Gwter Fawr spread through the country; the light of the furnace went like the break of day across the hills to stir the people of Gwynfe to venture across the mountain."

As industry grew, the population of the area increased significantly. The incomers were mainly from Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire, and this is probably the reason for the persistence of the Welsh language in the Amman Valley to this day.

Like most of his coevals, W.W. started work when he was only a child. As a boy working in the Tri Gloyn level he was paid eight pence a day for 'carting', that is, pulling a sort of sledge full of coal. Although educational opportunities were scarce on the whole, he managed to attend schools of some kind from time to time. The quality of the schoolteachers varied greatly. One was a butcher and another an old soldier, who, according to W.W, had given up on killing the enemy and was now half-killing the children. But Henry Jones was also a teacher in Brynaman. Later, as Sir Henry Jones, he became well known as a philosopher and was given the chair of the subject at Glasgow University.

Later in life, W.W. insisted that the best school he attended was the one held by his fellow colliers in the bowels of the earth. This was a Welsh school, with no trace of the unspeakable "Welsh Not"' (at this time pupils were banned from speaking Welsh during school hours). In his own words:

Every lunch time we had a class for reading or writing in Welsh, or making a speech, or composing a verse or singing a song.

Literary competitions were held and the compositions were written in chalk on a piece of stone. According to W.W., it was at one of these that he had his first eisteddfodic success for crafting a verse on the subject Y Ci Kipar [the dog Kipar]—with a box of matches as the prize.

There was certainly a bardic tradition of a kind in the Aman Valley, but according to Jonah Morgan the poets of the area "knew hardly anything about the lexicons, grammars or rules of poetry." It is also evident that they were not familiar with the strict metres and that no bardic tradition of this kind had developed in the area. This is not surprising considering that there was no notable manor hereabouts to foster poets, and that the inhabitants were mainly churls in the Middle Ages. The laws did not allow the child of a churl to take up the office of a bard.

Although examples of indigenous verse are scarce before the 19th century, Dyfnallt averred that "It was out of the literary and poetic tradition of earlier times that the rich harvest of the later years grew." According to Jonah Morgan, the chief diversion of the old poets was 'composing verses to each other.' And according to Thomas Levi:

Most of these poets were illiterate and were not scholars enough to put their compositions down in black and white.

Therefore, it was the tradition of the rural bard that flourished in the area, and these peasant poets were rhymesters and tripleteers.

Owen Dafydd was an exception, and W.W. said that it was hearing of his history that attracted him to poetry. Although he was a miller by trade, he was also a balladeer who sold his compositions at fairs. According to the memorial on his grave in Ystradgynlais cemetery, he was born in Gwynfe in 1751 and died in the mill at Gurnos in 1813. Nevertheless, he spent part of his life in the mill at Cwmgrenig in Cwmaman, and according to the Revd Glasnant Jones, W.W. claimed that his family and that of Owen Dafydd were related. The old poet's most famous ballad was on the subject of 'Christ's Divinity'. The background of the ballad was the squabble that occurred after Josiah Rees led Gellionen chapel towards Unitarianism. Owen Dafydd was a Calvinist to the bone, and his anger was great towards those who denied Christ's divinity; he enjoined them to study the Scriptures.

But if it was hearing about Owen Dafydd that sparked Watcyn's interest, the man who became the teacher to him and other budding poets of Brynaman was Daniel Lewis Moses. Moses hailed from Cribyn, Cardiganshire, and he was one of those who moved to the area to find employment in the ironworks. He came from a district where the bardic and eisteddfodic traditions were deeply rooted. He himself was a poet and a master of cynghanedd. More importantly, he was interested in nurturing young poets, and according to Watcyn Wyn he was considered to be 'the literary father of the area'. At his feet were reared a nest of poets that included Gwydderig, Gwalch Ebrill, Meurig Aman, Tegynys and of course Watcyn Wyn. They were masters of cynghanedd and drunk on poetry. According to Penar Griffiths:

They hit each other with cynganeddion like children throwing snowballs.

Their early efforts appeared in the poetry column of 'Y Gwladgarwr', and that perfectionist, Caledfryn, editor of the column, criticized them harshly at times. But these were the times of the 'penny readings' and eisteddfods large and small, and the fever of competition caught hold of W.W. and his friends early, and, as we shall see, not to their advantage.

In 1870, while he was still working in the colliery, W.W. married Mary Jones, a girl from Trap, near Llandeilo. After just eleven months his wife died, leaving a little girl three weeks old. In a tender and emotional poem he expressed his sadness following the loss:

Do you remember,

when in the arms of love

we strolled across the meadow,

tender talk of the one who would be left behind?

One of us now remembers,

Remembers every word,

yes, remembers and feels

and weeps alone.After this bitter experience W.W. decided to change the course of his life, and the first step was to secure the advantages of a formal education and leave the colliery. In 1872, the people of Brynaman arranged a concert, the takings of which went towards funding his education.The sum of £34 was raised and this assisted him in enrolling in the Tydvil Academy in Merthyr, which was run by his uncle, Evan Williams. His initial aim was to gain qualifications as a colliery manager, but he was urged by his friends to start preaching and to consider a career in the ministry. With an eye to this, he moved to Carmarthen in 1875 and spent a term in Parc-y-Felfed Academy in order to learn Greek and Latin. Then he spent four years in the Presbyterian College there. While at Carmarthen he married Anne Davies of that town.

English Baptist Church in Brynmawr Lane was briefly Watcyn Wyn's school, 'The Hope Academy, before Gwynfryn was built in a field next door. Watcyn Wyn's school, Gwynfryn, on College Street, Ammanford and the original 'college' of College Street. Now a private residence called Gwynfryn. Gwynfryn School, Ammanford

After leaving the college, he failed to secure the ministry of a chapel. It appears that he was not an inspirational preacher, because of his tendency to read his sermons word for word. He decided, therefore, to pursue a career in teaching and he secured a post in a school in Llangadog. Owing to some unpleasantness he left there after a short time and he went with some of his pupils to set up a new school in the Cross Inn (latterly Ammanford) in 1880. The name of the new school was the Hope Academy and was held in the Ivories Hall in Hall Street. In 1882 it moved to Gellimanwydd Chapel (Christian Temple) then to a former barn in Brynmawr Avenue. Then in 1888 a new, larger house was built on adjoining land. It was called Ysgol Gwynfryn (Gwynfryn School), and it became well known throughout Wales as the nursery of a host of ministers, such as Gwili, J.T. Job, Nantlais, T.E. Nicholas and H.T. Jacob. W.W. was headmaster of the school for the rest of his life and gained a reputation as a born teacher.

The old Hope Academy still stands on Brynmawr Avenue and is still in use today as the English Baptist church and Gwynfryn House was bought for use as a private home after the closure of Gwynfryn College in 1915.

During this period, he and his friends from Brynaman continued to write poetry although many of them, such as Tegynys, Gwalch Ebrill, Meurig Aman and Gwydderig emigrated to America. W.W. was very successful and the purses he received helped to support him during his college years. Often, he was tempted, like most of the poets of the period, to compete on entirely unsuitable themes, to the detriment of the literary standards of that time. He won a host of eisteddfod chairs and crowns and he gained national recognition when he won the crown for a pryddest on the theme Bywyd (Life) in the Merthyr National Eisteddfod in 1881. In 1885 he went a step farther by winning the chair in the Aberdare Eisteddfod on the theme Y Gwir yn Erbyn y Byd (The Truth Against the World). The poems have little literary merit. They are long-winded, discursive and pseudo-philosophical and contain all the weaknesses of the eisteddfodic work of the period.

He continued to write poetry and in 1893 he was awarded the crown at the World's Fair Eisteddfod in Chicago for an epic poem on George Washington. The poet was expecting the crown and 200 dollars but he was disappointed in that he was sent only 100 dollars. This was a bitter experience for W.W. and he decided to turn his back on competition once and for all. Although he was as keen as anybody else in the pursuit of prizes, he realized, at last, that the influence of the eisteddfod on the literary standards of the time was pernicious. He accused poets of looking first at the prize and then at the set theme. He expressed this in some sarcastic lines:

The bard sings his love song

for the prize, not for the girl;

today silver and gold are more alluring

than the charms of love and the smiles of a gentle lover.In poems like 'The Complaint of the Unsuccessful Competitor' he makes fun of the tendency that he was once a slave to:

Poets and poetry almost fill the world,

there are still literary meetings every week,

every newspaper with the names of countless winners,

but never do I find my little name.So great was the desire to win in some poets that they would steal each other's work. In the poem 'Plagiarism' he refers to this sin:

They steal from everyone except themselves, poor souls;

they would even steal from there if there were something to be found.

But I sometimes saw five, six or seven of them

catch each other out before now.In these poems W.W. managed to free himself of the eisteddfodic shackles and give expression to his flair for satire and his natural humour. He also possessed the gift of being able to wed verse with melody, and he had the opportunity to do that by writing hymns. This gift came to the fore first of all when he translated into Welsh the hymns sung in the meetings of the American evangelists, Ira D. Sankey and Dwight L. Moody. These two visited Wales in 1875 and 1882 and thousands flocked to see them. The main attraction was, perhaps, the hymns of Sankey, and in 1874 a collection of these was published in a Welsh translation by Ieuan Gwyllt under the title of Swn y Jiwbili (The Sound of the Jubilee). This became a popular volume since the hymns were simple and were sung to the popular tunes of the Music Hall.

In 1882 W.W. translated some of the hymns, and the first edition of Odlau'r Efengyl (Rhymes of the Gospel) was published in that year. They are mainly adaptations of the hymns contained in the 'Sacred Songs and Solos' of Sankey, and their chief characteristic is their simplicity of language. They are also free of the Calvinistic theology that marked so much of Welsh hymnody. The emphasis is placed mainly on the person of Christ and in Odlau 'r Efengyl there are titles like Dim on Iesu, Dewch at Iesu, 0 Iesu beunydd gyda mi, Iesu sy 'n dyfod, Gyda 'r Iesu, Canlyn Iesu. The following sentiment reflects the hope that flows from the sacrifice on Calvary:

If I have Jesus, only Jesus,

my heaven will be all light,

the sun will have risen

on my life in the world.And also:

I sing of the costly sacrifice

made on Calvary;

within the Right that keeps the world

there is a means of keeping me.Sankey's hymns have been referred to as: 'The refuge of the dispossessed people of industrial America and England.' Therefore there is a strong emphasis on hope and the promise of a better life in the hereafter. The image of the 'Beautiful Land' is a common one:

In the perpetual summer's day, on the heavenly shore,

we will meet our dear friends soon;

no-one dies in the beautiful land,

there is no end there to pure pleasure.The same kind of joy is found in W.W's original hymns:

I love the name of the beautiful land,

the land beyond the grave,

where there is pure unmixed pleasure,

where there is eternal peace ...For him, the hymn is an instrument of praise and inspiration.

O lovely, blissful hours

when we forget the world,

in the sound of the old hymns

that are all song and praise;

there is an air of inspiration

pervading these,

and the heart of humanity

leaping in their sound.Simple language expressing hope is characteristic of several other hymns, like Esgyn gyda'r lluoedd, Canaf am yr addewidion, and of course the most famous, Rwy'n gweld o bell y dydd yn dod. This was a hymn composed for Y Caniedydd Cynulleidfaol [The Congregational Hymnal], which was published in 1895, the centenary of the Missionary Society. The story goes that the hymnist was on holiday in Newquay when he was inspired by the breaking dawn:

The fair light of dawn,

from country to country, says now

that the morning is nigh;

the hilltops are rejoicing

on seeing the sun approaching

and the night in flight.There was another mission close to W.W's heart, namely restoring the harp to its proper place on the nation's stages. In the Victorian age the harp was respected less than the piano since it was connected with a more wanton culture. According to W.W:

There is a fear of the old Welsh harp

in the breast of the religious man,

and a belief that the songs of fair Wales

and its muse are ungodly.In the inaugural ceremony of the Brecon National Eisteddfod, 1889, the committee decided that it would be a good thing to have verses sung to harp accompaniment as part of the Gorsedd ceremony. Only W.W. responded to the challenge. The verses were sung by Eos Dâr and they were warmly received. From then on the practice became an essential part of Gorsedd ceremonies for a period.

Following this, W.W., Eos Dâr, and the harpist, John Bryant, arranged a series of talks called 'Evenings with the Harp'. Such talks were held all over Wales and even across Offa's Dyke. The enthusiasm was incredible and in less than a fortnight in November, 1900, ten 'evenings' were held from Aberdare to Fishguard. In 1895 W.W. published the volume Can a Thelyn, and from this time on he had he opportunity to give free rein to his gifts as a satirist, humorist and a story teller in song. The triban (triplet), the verse for harp and the ballad were perfect vehicles for his innate ability as a social poet.

He attacked many prejudices of his time and a subject close to his heart was the lack of respect for Welsh within the educational establishment. When on a visit to Lampeter College he condemned the practice of promoting Greek and Latin at the expense of Welsh:

He who knows Greek and Latin

is an uncommon scholar;

in not knowing the language of the country he loves

he is uncommonly foolish.The personable authorities

of our colleges

ask why we might not have more work

in the holy language of our saints.On his visit to Jesus College, Oxford, he made fun of Dic Shôn Dafyddion:

You have heard of the clean-cut boy

who went to the town to learn English,

in the end returning

with neither Welsh nor English.In the Circle of the Gorsedd in Cardiff National Eisteddfod, 1899, verses were sung that are rather prophetic in the light of the growing demand for education in Welsh in the south:

Today in our big cities

everybody is becoming one of the Cymrydorion;

the English are busy buying books

to learn the language of the thousand years.The fine, dead languages

will have no place in future education.

Greek and Latin will have gone mouldy

and the language of Wales will be flowering.W.W. was also a strong pacifist, and this during the war in South Africa against the Boers. He admired Lloyd George, who was very unpopular because of his opposition to the war. In his poem, Cadw'r Heddwch (Keeping the Peace), he shows the irony of the contemporary situation:

In the coming age a gun and dagger

will be seen in every hand.

We must learn to spill blood,

or peace will be trampled underfoot.In the same way he attacked the evils of capitalism and the poverty and distress visited upon ordinary workers:

Silver and gold to buy the coal

that lurks under the mountain,

say the men with silver and gold

as plentiful as gravel and always striving for more.

You poor of the land—dig into your pockets.

Coal is cheap and the great men in hardship.The old poets of Dyffryn Aman were fond of putting amusing stories to song, and W.W. inherited this gift. This can be seen in ballads like Milgi Deio Cwmgarw and Cloc Llandeilo. When a clock was installed in the church tower at Llandeilo it was decided that the tax-payers had to pay for its upkeep and for raising the weights (ie ringing the bell). Some Nonconformists refused to pay towards maintaining 'a clock of the Church', and there was some fuss about the matter. W.W. saw the humour of the situation:

The clock moves unconcernedly,

although it still strikes;

Llandeilo is debating

who is to raise the weights regularly.Some say it is providential

in the belfry of the Established Church

to warn of death

and to strike the hour of interment.This is indeed a liberal clock,

a clock for all—not just a few,

a clock whose hours are like missionaries

to preachers and parsons.What is striking about W.W's life and work is the breadth of his interests and the extent of his activities. He contributed regularly to the journals of his day, like O.M. Edwards' Cymru and denominational periodicals like Y Dywigiwr and Y Traethodydd. He published 35 books, including poetry, hymns, prose and songs. But in the end he may have published too much and at times was too ambitious. He translated Shakespeare's 'Measure for Measure' into Welsh but there is scarcely any literary merit in his translation. In partnership with Elwyn Thomas he wrote two novels, Irfon Meredydd, and Nansi, Merch y Pregethwr Dall, but he failed to master the craft of the novelist. Although he was adept at cynghanedd he was not as successful as Gwydderig as a writer of englynion. Nevertheless, some of his englynion stay in the memory, such as this one—Tynnu 'r Dant Hir (Pulling the Long Tooth):

Tugging for an hour or more, – the bad tooth,

incredibly long tooth;

the terrible eye tooth,

long tooth, a mile or more.Gwynfryn Chapel, Ammanford

In 1903 a new chapel was built in College Street, Ammanford, and Watcyn Wyn was invited to preach the first sermon. The chapel was named Gwynfryn, appropriately enough, as it stands opposite the school Watcyn Wyn founded in 1888, Gwynfryn School.

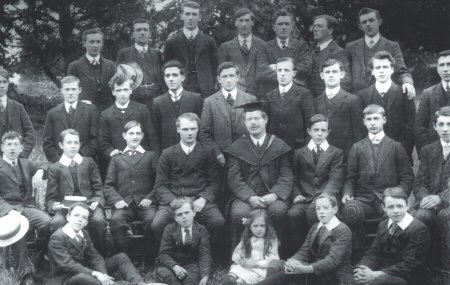

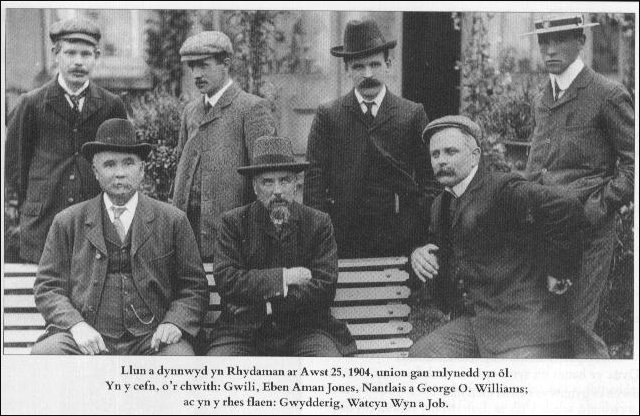

Photo: Watcyn Wyn (middle of front row) in 1904 with a gathering of pupils and friends. His son George O. Williams, who became the first headmaster of Amman Valley Grammar School in 1914, is top row, far right. Local Methodist minister and poet Nantlais is top row, third from left. A biography of Nantlais can be found in the 'People' section of this website, or click HERE. Poet John Jenkins (Gwili) who became Watcyn Wyn's successor as headmaster of Gwynfryn is first left, top row. Gwili can be found in the item on Edward Thomas in the 'People' section, or click HERE. The text below the photo reads: "Picture taken in Ammanford on August 25th 1904, a hundred years ago. In the back, from left: Gwili, Eben Aman Jones, Nantlais and George O. Williams; and in the front row: Gwydderig [Richard Williams], Watcyn Wyn and [J. T.] Job." (Photo from Summer 2004 edition of 'Barddas'). W.W. is chiefly remembered today as a hymnist, but in his day he was a prominent figure in the Welsh public life. He had definite ideas about the future of the National Eisteddfod and he tried to use the Gorsedd ceremonies to reinstate the harp into the life of the nation. As a schoolmaster his influence on many of the young people of the period was great. His home in Ammanford was a popular haunt of many famous people, such as Sir John Rhys, Sir Edward Annwyl and Joseph Parry, and to poets and others such as Hwfa Mon and Gwili. English poets such as Edward Thomas, later to die in World War One, also visited him.

On the whole, his health was fragile throughout his life. He suffered terribly from shortness of breath—probably a consequence of his early days in the colliery. In 1904 his condition worsened, and in a letter written in February he said:

I have not been in good health since last summer, and I feel that I will never be wholly well again.

He worried greatly about the state of the world and particularly about the wars on different parts of the globe. In the same letter he wrote:

I am not despondent or without hope but tired, and rather impatient on seeing the world so stupid and sensible men so blind.

During the months of November and December his health deteriorated further and there were fears for his life. Nevertheless, Gwili could testify that "his wit flowed despite the coughing and pain". He had some consolation on hearing about 'The Revival' that swept through the country in 1904. By November, 1905, he was gravely ill and on the 19th he died at home. His old friend, Gwydderig, was at the bedside. As the dawn broke and the sunlight settled on the bedcover, W.W. said quietly:

Golau ddydd i'r gwely ddaw. (Daylight arrives at the bedside.)

Thousands flocked to his funeral—a testimony to his popularity in his own locality and in the country as a whole. He was buried in Gellmanwydd, Ammanford, and on his gravestone are the words of Gwydderig:

The name of Watcyn Wyn is not seen—a day

and he will have to be put in a shallow grave.He also wrote this englyn for the occasion:

On the land of the new chapel—the monument

of the bard can be seen;

his sick body is at rest

in the graveyard of Gellimanwydd.W.W. was a product of that rich culture that flowered on the fringes of the Black Mountain, and especially in Brynaman, in the second half of the 19th century. Through education he succeeded in escaping from the confinement of the colliery and to claim a more prominent place in the life of Wales. In spite of that, he kept his roots deep in the Aman Valley, and in his personality and his best poems can be seen that warmth and humour that is so characteristic of the people of the anthracite coalfield. In his poem to him, Gwydderig succeeded in summarizing all that can be said about W.W's life and work:

The unassuming Watcyn was the people's friend,

and his ready words like drops of fine wine;

poet, prominent author, a teacher to cherish,

he was laid to rest, his dazzling name untarnished;

the closing of his lips was a wound to an age – a hero whose talent was like refined gold.When Amman Valley Grammar School became a comprehensive in 1970, one of the school houses was called 'Watcyn' in his memory.

(The other houses in the new comprehensive school were also named after local poets, namely Llwyd, Amanwy and Nantlais. The houses in the former Grammar School had been named after Welsh princes —and warriors—Hywel, Glyndwr and Llewelyn, with the patron saint of Wales, Dewi, being the sole exception. An improvement in whom we should regard as role models, perhaps).

Source:

The above is a summary of an article by W. J. Phillips in Cwm Aman, edited by Hywel Teifi Edwards and part of Cyfres y Cymoedd (Series of the Valleys). The original, as is the whole series, was written in Welsh. This translation has been made for this website.

Date this page last updated: July 7, 2003