The 'White House' in High Street, Ammanford, now a private dwelling, was once a centre for study and discussion for a group of local miners at the time of the First World War. Although the White House was only in use from 1913 to 1922 its later renown was such that it attracted the curiosity of academics from as far afield as distant England. The following article by T. Brennan about the White House was published in the 'Cambridge Journal' in 1954, which explains why he refers to several people only by their initials, as they were still very much alive and thriving at that time. These people have been identified wherever possible, either in a footnote or within square brackets [... ]. The photographs have been introduced for this website.

THE WHITE HOUSE

by T. Brennan

The Cambridge Journal, 1954Students of the sociology of politics agree that political activity must be studied at all levels and in particular that the working of democracy can best be understood if account is taken of the small Informal and unattached groups in which individuals exchange and test their opinions. At the same time many of those active in politics, particularly of the 'left', would like to see a revival of the enthusiasm of the period before the first World War when men and women throughout the country met in small groups and classes such as those of the Independent Labour Party and the Workers' Educational Association, confident in their own ability to shape a better society and eager to examine any tools which promised to be useful.

In the course of a sociological inquiry in South West Wales the activities of one such group of enthusiasts were mentioned several times in connection with political development in the area, and it was thought that a more complete investigation of the history of the group might be worth while.

The group referred to was formed just before the first World War and operated for about ten years in the anthracite mining town of Ammanford, not far from Swansea in South Wales. Its members were almost entirely young miners and the group concerned itself with free intellectual and political discussion. There was nothing remarkable about it except perhaps that it had a permanent building of its own – the 'White House' of the title of this paper. The acquisition and use of the building provides a convenient focus for the story of the group. In its other features the story simply reflects the forces which were at work generally in society and could probably apply to other groups in many parts of Britain. Even the acquisition of the building might be regarded as a typical example of the middle class philanthropy and interest in working class education which was so important to the success of such movements as the Workers' Educational Association.

The White House was the name of a building near Ammanford, originally a vicarage, which was bought by a wealthy individual named George Davison, in 1913, and handed over to a group of young men for use as a centre for free discussion. [see Note 1 below]

George Davison, benefactor of the White House in a suitably pensive pose (1918) Davison himself was an eccentric individual who, having made a fortune in connection with a Kodak agency, devoted some of it to philanthropic purposes. Politically he was described as a Kropotkin-Anarchist; he was said to have lived largely on a diet of fruit and nuts, and he also adopted and cared for several backward or ailing children of London ex-cabmen. Thomas Jones in his 'Welsh Broth' tells how in '1909 or later' Davison invited several members of a Fabian Summer School being held at Llanbedr, Merioneth, to his home near Harlech. The members included Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Professors Tawney and Namier, George Lansbury and Thomas Jones himself. It was probably from this meeting that the project for turning Davison's house into a residential workers' college started. Some years later, Davison did in fact hand over his house on very favourable terms for this purpose. It is now known as Coleg Harlech and annually provides residential courses on social subjects for mainly working class adult students. Thus Davison was in touch with the workers' educational movement before he had any connection with the White House at Ammanford.

Davison provided the White House itself in 1913, but the group of young men who ran it and made use of it had been in existence at least two years earlier. [See Note 2 below] Similarly the group had more or less disintegrated before the house reverted to Davison's estate in 1922.

Most of the members of the original group were well known to each other. Apart from one tinplate worker, they were all miners and worked at the same colliery. All were active members of their miners' lodge and all except one were unmarried. More or less the same individuals comprised the local branch of the I.L.P. (Independent Labour Party) and since as young men they felt restricted by the older members of the miners' lodge, they decided to meet separately. They normally met in the kitchen of the house of the one member who was married. They were, as they styled themselves, 'the progressives' of the lodge. All were interested in the wider issues of politics and were keen readers of the pamphlet literature of the period. All witnessed the great religious revival of 1904-5, the drive for unionization and federation in the mines and were aware of living in a time of great promise. Many of the older members now look back on the period as one of great awakening. If their memories are to be trusted, the district received and listened to a constant stream of missionaries representing in turn the Miners' Federation, the Central Labour College, the Workers' Educational Association, the I.L.P. (Independent Labour Party) as well as Christian Scientists and propagandists of the many religious sects which had arisen following the revival. They remember too the crowds, the excitement and examples of powerful oratory. The fact that they remember little of the issues which were discussed at these meetings might be explained by the fact that many of the issues which excited them would now be accepted without question. On the other hand, It might be significant that though all the older members could remember attending meetings addressed by two brothers who were popular speakers in this period, there was no agreement as to whether they were Christian Scientists, I.L.P. speakers or members of the Apostolic Church. There is documentary evidence that the two brothers were in fact American Christian Socialist missionaries from California, and it is likely that they appeared at meetings organized by various bodies. Nevertheless, the impression given is that, even at the time, these various meetings were regarded by many people as all part of the same movement – an increasing awareness among Welsh workers of the New Learning which had hitherto been denied them by barriers of language, religion and geography.

The members of the group which was later to become the White House group regarded themselves as being amongst the keenest seekers after knowledge. In 1911 two of them, D. G. and H. A. [the married member – see Note 3 below], attended a competitive examination in Swansea for a trade union scholarship to Ruskin College, Oxford. It was in fact during the railway strike of 1911 and on the day that the army was called out to restore order in Llanelly. No trains were running and they cycled the double journey of 16 miles in each direction.

H. A. was unsuccessful and continued his efforts with his own political discussion group. D. G. was given a scholarship and after a session at Ruskin returned to work in the pits. At the same time another miner from a neighbouring colliery, D. R. O[wen] (a checkweigh-man), was attending Ruskin College, and they both met Davison there; there is little doubt that the two Ruskin students formed the link between the Ammanford group and Davison.

In 1913, on the invitation of the group, Davison visited Ammanford and bought the White House which he handed over to the group on the condition that it was to be maintained as the headquarters of a free discussion group – unattached to any political party. One of the early group, now married, was given rooms in the house free of rent in return for his services as caretaker. This arrangement lasted about a year, when H. A., the convenor of the original group, was installed with his family on the same terms. He continued to work in the pit and his wife acted as caretaker while the group held the house.

The White House did function for a time as Davison had intended. Speakers of various religious denominations and various political opinions were invited to address meetings which were often open to the public and were well attended. The most popular speakers included Noah Ablett of the I.L.P., a dentist and a schoolmaster from Llanelly, who were active propagandists for socialism, and a local Baptist minister. There was, however, in this period, in the minds of many people, identification of Socialism with Atheism and Agnosticism, and many of the young men joining the group thought it their duty to leave the chapels as a sign of their maturity. The White House became known as the meeting place of 'a lot of queer atheistic revolutionaries'. With the outbreak of the 1914 War the group was inevitably labelled pro-German and unpatriotic, and in fact towards the end of the war returning ex-servicemen threatened to demolish the house with dynamite. All that happened was that a few pieces of rubbish were thrown into the yard of the house, but it is sufficient to show that the group was not universally popular.

Several members of the group were against the war and objected to military service. Nine were arrested on the same day for refusing to obey the call-up and some of their friends were anxious to turn the occasion into an anti-war demonstration. Other and more pacific individuals made an agreement with the police that the nine objectors should be delivered to the railway station without police or military escort, apparently to show the police that they were neither cowards nor trouble makers and were proud to testify to their convictions. The nine were in fact delivered in orderly fashion and served varying terms of imprisonment. Other members attached to the group from time to time organized to boycott recruiting meetings, but since most of the eligible men were miners and for a long time exempt from military service, the issue was not as important as it might have been. There is no strong evidence that the White House acted as a group formally organized for political action. In other words it still functioned as a centre for free discussion.

Gradually, however, the young men who had come together in their enthusiastic search for knowledge found in the programme of the Labour movement ample scope for their energies. Most of them were members of the I.L.P. and almost all became members of the Labour Party at the end of the war mainly via the local Trades Council, which was set up to provide workers' representatives on various official joint advisory committees. Then too, the Socialism for which they had fought was given official definition in the new constitution of the Labour Party [this was 'Clause 4' of the constitution which promised nationalisation of the major private industries and was eventually scrapped by the 'New' Labour party in 1995]. The expansion of the labour force in mining also tended to give more power to the younger men in the unions and some set themselves to build up the strength of the unions for the militant industrial action which was to follow 1921. In any case, by 1922 the agent acting for Davison claimed the house on the grounds that it was no longer being used for its intended purpose, and the White House group officially ceased to exist. By this time other premises were available in Ammanford, but in fact no effort was made to replace the White House since its members had found their place in the Labour movement and were fully occupied as union, party and local government officials.

Gradually, the more active members not only rose in the hierarchy of the Labour movement, but in effect moved out of the working class altogether. Significantly too, many of them rejoined the chapels. Of the original dozen most active members, the secretary rose by the now established route of union official, local councillor, Labour M.P., to Cabinet Minister [See Note 4 below]. D. R. O.,[ D R Owen] the checkweigh-man of the foundation group, after a period at Ruskin, returned to the area as lecturer for the National Council of Labour Colleges, though continuing to work at the pit. He later became a councillor, then county councillor and was finally a full time Food Officer during the 1939-45 war, from which job he went into retirement.

One of the conscientious objectors became manager of the local Cooperative Society and served for more than twenty-five years [Edgar Bassett – See Note 5 below and see also the article on 'The Pick and Shovel, the Creation of a Workingman's Club' in the 'History' section of this web site]. Another, also a county councillor, now holds a well paid administrative post in industry. Several less prominent members entered local government and some are still county councillors. At least one is a university lecturer and one a university professor. Of the remainder of the group two or three maintained what they called 'their independence of thought'. One of them vowed never to work for an employer and made his living for many years as a hawker before opening a fish and chip shop, which is still run by his widow. Two others, though never interested in direct political action, still maintain their interest in social affairs, through reading.

In some ways even more interesting than this record of personal achievement are the records of the families of those who were active in the group – either their sons or their brothers or brothers-in-law. In proportion to its size the town of Ammanford, with a population of about six thousand, has produced a large number of men who have made their mark in political, academic or musical circles. And though in a small town each family has many connections, it is surprising to an outside observer to find how many of those who have 'made good' are found to be related to the original dozen members of the White House. Incidentally, something like the same result was obtained in a similar though more formal investigation for the whole of the Swansea area (which includes Ammanford). In seeking to discover the place of the working class trade union or chapel leader in his community, it was found that the adult sons and daughters of such leaders had risen from jobs of working class to those of middle class status very much more frequently than groups of comparable age in the rest of the population. Furthermore, it was found that comparatively few of the successful second generation showed the same interest as their fathers in political and social affairs.

The story told here of one small group may have no general significance at all. If it has, the conclusions which it suggests are as follows. First, that the group functioning as an independent body and with premises of its own provided a valuable method of education for its members. It is unlikely that the Labour Party, the Miners' Union or even the educational associations could have provided the conditions which enabled working class men after only a few years to take their place with such confidence and ability in the running of the affairs of their own and the national community.

Secondly, there is the fact that, active though the group was, it never succeeded in attracting a second batch of young men to take the place of its founders. It is only to be expected that young men who seek the truth will satisfy themselves that after a few years they have found it in a political programme which they have helped to shape. It is less easy to explain, however, why they had no successors. The answer to this question, as well as the answer to the question of whether it would be possible to revive the activity of such groups, is probably to be found in wider social changes which are taking place and are even more noticeable in South Wales than elsewhere in Britain. In the first place opportunities for promotion of any kind in a mining community were so scarce that inevitably a vast amount of talent was left among the miners. The type of political activity which has been described provided some outlet and, incidentally, some chance of advancement for the most able. Educational opportunities have now improved so much that such talent is filtered off, and in so far as ambition, diligence and intelligence are inherited or acquired in the family, the potentially most active families are removed from this sphere of social affairs. In addition to the factor of better opportunities there is the deeper reason that the socially approved career, to which the most able might aspire, has itself changed. To be a respected trade unionist and also a chapel deacon, no longer represents the ambition of young men. The infiltration of English standards, and particularly English middle class standards of personal consumption, shapes the career which replaces that of the village elder. In such conditions the revival of groups like the White House group as an important part of political life seems very unlikely.

[Source: The Cambridge Journal, January 1954, pages 243 – 248.]

Note 1

George Davison (born 1854 in Lowestoft, England and died 1930 in Antibes, France) was a noted British photographer, a proponent of impressionistic photography, a founder member of the London Camera Club in 1885 (serving as its secretary in 1886), a member of Royal Photographic Society, a co-founder of the Linked Ring Brotherhood of British Artists in 1892, and the managing director of Kodak UK. George Davison very strongly marks the history of photography, and especially that of the English pictorialism. He was also a millionaire, thanks to an early investment in Eastman Kodak.Davison was an audit clerk at the English Treasury until he went to work for Kodak UK Ltd in 1897. By 1898 he was its managing director and served on the company's board of directors, becoming very rich from stock options but was forced to resign from the company in 1912 due to his anarchist associations. He purchased the White House the next year. He later retired to Antibes in the South of France where he died in 1930. (On George Davison, see Brian Coe, 'George Davison: Impressionist and Anarchist', in Mike Weaver, ed., British Photography in the Nineteenth Century, (Cambridge, 1989), 215-43 There is also a more detailed summary of his life in the 'People' section of this website).

Note 2

The founding members of the White House brought with them a reputation for radical political thought even before the study centre opened its doors. The town was overwhelmingly Non-conformist in worship and Non-conformism gave its political backing to the Liberal Party, so socialism in the town was seen as a very real challenge to their authority. The local newspaper reported the opening of a 'Communist Hall' in Ammanford, even though the Communist Party of Great Britan would not be formed until 1920:Ammanford Socialists are fortunate in having secured the patronage of Mr Davidson who has purchased for them the old vicarage and had it converted into a 'Communist Hall' under which title it is being formally opened. (Amman Valley Chronicle, October 16th, 1913)

Note 3

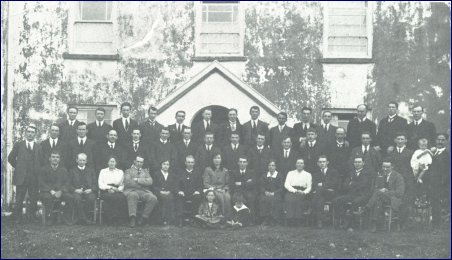

H. A. was Henry (Harry) Arthur who can be seen in the group photograph above, at the far right of the second row, holding his son, Donald Ramsay Arthur (the middle name was after Ramsay MacDonald, leader of the Labour Party at the time, and future Prime Minister in 1924). In adulthood Donald Arthur became Dean of King's College, London University, and a leading authority in the field of entomology (the study of insects). The hostility shown towards the White House group in Ammanford was so great that the local chapel even refused to marry Harry Arthur and his wife because of the presence of atheists in the White House.Note 4

This was Jim Griffiths who became MP for Llanelly in 1936 – see three articles on Jim Griffiths in the 'People' section of this web site. Griffiths became Minister for National Insurance in the 1945 post war Labour government and the first Secretary of State for Wales under Harold Wilson in 1964.In 1973 James Griffiths himself remembered the years of the White House:

"In our West Wales anthracite valleys the activity of two Labour college students, D. R. Owen and Jack Griffiths, was to lead to the establishment at Ammanford of an institution which, in its time, won some notoriety and, more important, came to exercise considerable influence on the industrial and political life of the area. Among the supporters which the Labour college had attracted was George Davison. Davison had been in the civil service in his early years. Through his hobby, photography, he had become associated with the establishment of the firm of Kodak in Britain. This had brought him considerable wealth and some of this he gave freely to the Labour college and to movements which the students formed after their return home. One evening he came to the economics class at Ammanford, of which D. R. Owen was the tutor and I was the secretary. The class was held in the dingy anteroom of the local Ivorites Hall. Whether it was because of the dinginess of the surroundings or the brightness of the students, or perhaps both, Davison told us he would provide us with a better meeting-place. The old vicarage in the High Street was on the market, and he acquired it and transformed it into 'the White House', so called because the old house was given a coat of white paint like his home on the Thames.

......Davison had come under the influence of what he used to describe as the 'philosophic anarchists', and when the White House was refurnished he provided the nucleus of a library, stocked with the works of Peter Kropotkin and Gustave Hervy. We formed an organization to which we gave the name the 'Workers' Forum', and for some years the old vicarage became the centre of socialist activity in the valley. There would be classes on most evenings, and Sunday evenings after chapel hours there would be lectures on a wide variety of topics. During the war years of 1914–1918 it became the home of those who were opposed to the war and there were times when the authorities eyed it with suspicion. From its classes and gatherings emerged a team of young men and women who became leaders in the industrial and political life of the valleys in the post-war years and their influence lasted beyond the time of the closing of the White House.

...... The 'White House Gang' and their opposition to war: We never thought it would come to war in Europe. To us Germany was the country of the most powerful Socialist Party in the world, led by the anti-militarist August Bebel. In France Jean Jaurès was at the head of a Socialist Party which had already become so influential that no Government could dare go to war against its opposition. At home the Labour Party had grown in Parliament, and in the country under the leadership of men like Hardie, MacDonald and Snowden. The Socialist International had resolved that, if ever war became imminent, the united force of European Socialism would be mobilized to prevent it by declaring a general strike. To our dismay, when war was declared on that day in August 1914 all was lost. In Germany August Bebel had to confess that 'race and nationalism were older and more powerful than class solidarity'. In France Jean Jaurès was assassinated, and his once great party overwhelmed in confusion and defeat. In Britain the Labour Party was divided, and even in South Wales we learnt that Keir Hardie had been shouted down in his constituency. In 1915, broken-hearted by the tragedy, Keir Hardie passed away. At the by-election which followed, a one-time militant miners' leader, C. B. Stanton, stood as a war supporter against the official Labour candidate, the miners' nominee James Winstone, and won an overwhelming victory. We in our own valley were derided, and persecuted, as the 'White House gang', the enemies of our country. In this hostile atmosphere a few of us endeavoured to hold on to our beliefs and convictions."Source: James Griffiths and His Times (ed. J Beverley Smith), pub. W T Maddock, Ferndale, 1981, pages 20-21.

Note 5

A reference to Edgar Bassett (1893-1949), the son of the Revd David Bassett, a Baptist minister at Gadlys, Aberdare. Edgar Bassett, known to Ammanford residents as 'Bassett y Co-op', was the manager of the Ammanford and District Co-operative Movement for twenty five years. James Griffiths wrote of him in 1949:'There were times when our unorthodox views made us something of a terror to our elders. But I think it can be claimed that we produced a generation of men and women who today play a full part in every phase of public activity in the neighbourhood, and every member owes something to Edgar Bassett'. (See 'Mr Edgar Bassett: A Tribute', The Amman Valley Chronicle, 27 January 1949.) Amanwy also paid him a warm tribute in his Welsh column 'Colofn Cymry'r Dyffryn', in the same edition of the Chronicle. See also '50 Years of Service and Progress, 1900-1950. Ammanford Cooperative Society Ltd., (Ammanford, 1950).

[The above note on Edgar Bassett was kindly provided by Dr Huw Walters of the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth]

POST SCRIPT

By the time of the White House's demise as a study and discussion centre, two political parties had grown to sufficient size and influence to provide alternative, better organised and longer lasting homes for people's political aspirations. These were the Labour Party and the Communist Party into which many of the men who attended the White House were swiftly absorbed.

The Labour Party, which we take for granted as one of the three main political parties in Britain today, is in fact a very recent creation compared to the other two, the Conservatives and Liberals. These were formed as long ago as the late seventeenth century due to disagreement over the succession of King James II and were initially called the 'Tories' and the 'Whigs', only taking their modern names of Conservative and Liberal Parties respectively in the nineteenth century.

In contrast the Labour Party was formed as recently as 1900, first under the name of the 'Labour Representation Committee' which then changed to the 'Labour Party' in 1905. The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was formed in 1920 in the wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution, and the White House provided the nucleus of the local branch, which soon became the largest in Wales outside the Rhondda-Merthyr-Aberdare triangle:

The town of Ammanford had been one of the most important foci of the Communist Party in the South Wales coalfield ever since the foundation of the party. Associated with its activities was the growth of Marxist education in the vicinity. In 1913 Labour College students such as D. R. Owen of Garnant and Jack Griffiths of Cwmtwrch had persuaded George Davison, a wealthy American anarchist, to buy the 'White House' outside Ammanford as a discussion centre for miners. Out of this grew an unusual local Marxist tradition and it was out of this nucleus of students that the Communist Party was founded. The Communist Party was significantly involved in two major events which broke the calm of the town in the inter-war period. The Anthracite Strike of 1925 which had its origins in the Ammanford No. I Colliery was characterised by unprecedented and violent rioting in and around the town. A decade later similar (although much less violent and dramatic) scenes were re-enacted during the transport dispute of local bus drivers. In this atmosphere, in which Communists played leading roles, many joined the Communist Party. The Ammanford Workingmen's Social Club, founded as a direct result of the 1935 dispute, soon became known as the 'Kremlin'. Its 'Blue Room', where only discussion of politics was allowed, displayed busts of Lenin and Keir Hardie. Two of its founder-members, the Communists Jack Williams and Sammy Morris, both of whom were involved in the 1925 and 1935 disturbances, were killed fighting with the International Brigades at Brunete in the Spanish Civil War. (Source:

(From 'Miners Against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War', Hywel Francis, 1984, page 204).

In 1922 the White House was sold at auction for £1,000 for use as a manse, in effect a reversion to its original role as a vicarage. It is doubtful, however, if the building was ever actually put to this use as shortly after the sale a private secretarial college known as 'Pagefield College' occupied the premises. Later still it became a veterinary surgery before finally becoming a purely residential dwelling in 1974.

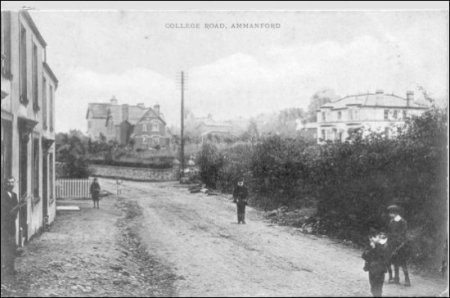

A farm house called 'Carregamman Uchaf' had originally stood on this site but at some point it had been demolished to make way for a vicarage for the parish of Betws. Completed in 1804, it was purchased by the Bishop of St David's in 1835 and seems to have become a vicarage from then on – it is certainly identified in the 1875 edition of the Ordnance Survey maps as 'Bettws Vicarage'. The 'White House' was used for this purpose until 1911 in which year the Reverend J. Walden Jones, (later to become the first vicar of the newly formed Parish of Betws-cum-Ammanford) bought himself a house in College Street and moved there to live.

Called 'Greenlands', it had been built in 1875 and was one of the first houses on College Street. It was lavishly set out with stables and a coach house, having an enclosure and grounds of 1.6 acres extensively landscaped with a large selection of trees and shrubs including a private bowling green. Many vicars of that era had private means and would certainly have needed them to purchase such a large and prominent dwelling as this. In 1913 the Reverend J. Walden Jones sold 'Greenlands' to the Church for the price he had paid for it and it became the official vicarage for the new Parish of Betws-cum-Ammanford from then on. The 'White House' was now surplus to ecclesiastic requirements and was purchased by George Davison in the same year for £300.

Nothing lasts for ever however and over time the new vicarage in College Street, a remnant of a bygone age, has proved too large and expensive for the pocket of modern ecclesiastics, who no longer have the private means enjoyed by some of their predecessors. So when the vicar of 1999 moved to another parish, the Church authorities used the opportunity to purchase and fit out a newer, smaller, semi-detached house in High Street, coincidentally opposite the original vicarage, the White House of our story. Some sort of circle seems to have been completed here, where both ancient and modern face each other across just a few yards of road. Ominously, however, the Church failed to find a replacement vicar for some years and both the old vicarage on College Street and the new one on High Street stood empty for that period. The parish of Betws-cum-Ammanford then found itself in possession of two fine vicarages, but had to wait until 2002 before it could acquire a vicar to occupy its new one. The old one, 'Greenlands', stood in splendid, if empty, isolation for a couple of years until bought as a private residence in 2004.

As we have already mentioned, the site of the White House was originally on a farm called Carregamman Uchaf (Upper Carregamman) which stood on the banks of the river Amman. Just half a mile downstream stood another farm called Carregamman Isaf – Lower Carregamman. Both Carregamman Uchaf and Isaf were bought at auction as far back as 1779 when they were adjoining farms. As both farm houses were on the banks of the river Amman it is almost certain that they included stone collected from the river bed, hence the name of the two farms – 'carreg' is the Welsh for stone and 'Carregamman' means 'stone of the Amman'. In 1885 St Michael's Church and its Hall were also built from river Amman stone – see the entry for 'St Michael's Church' in the 'Churches and Chapels section of this web site. Although both farmhouses have long disappeared, and their once extensive fields lie buried beneath Ammanford's concrete and tarmac, they at least still live on in name. The fields of Carregamman Isaf were eventually bought by Ammanford Urban District Council in 1948 who built a housing estate of 50 prefabricated houses on the site, naming it Carregamman.

The fate of Carregamman Uchaf we have already seen and its name, too, may still live on, albeit indirectly. The fields of the old farm have long disappeared, now forming part of Ammanford's modern fabric of streets and buildings but the road that passes over them has been called 'High Street' at least as far back as 1831 when the name appeared on the first Ordnance Survey map for our area. A literal translation of 'High Street' into Welsh would be 'Stryd Uchaf' and it is tempting to surmise that this name was initially given to the road by locals because it went past Carregamman Uchaf and was later translated to 'High Street'. (The Bible however, exhorts us to resist temptation, so we shall refrain from such speculation.) . The local council has also shown exemplary restraint in this matter and in and in keeping with its policy of bilingualism of street and place names, has given the Welsh name of 'Stryd Fawr' – 'Great Street' – to High Street and not 'Stryd Uchaf'. Dr Huw Walters of the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, has provided the following information for 'High Street':

Local councils are seldom correct when it comes to Welsh place names, but Ammanford Council is, more or less, right with 'Stryd Fawr' when it comes to High Street. 'Stryd Uchaf' is a direct translation of the English; it looks and sounds silly as 'Stryd' is non existent in south Wales Welsh, and local Ammanfordians referred always to High Street as 'yr Hewl Fowr'.

What's in a name, the Bard of Avon once asked, and perhaps we too should shrug our shoulders and leave matters there.