JOHN JENKINS

(BARDIC NAME: GWILI)

(1872-1936)

Poet, Theologian

and Man of LettersFrom the village of Hendy on the Carmarthenshire side of the river Loughor, John Jenkins (bardic name Gwili) had a strong and long-lasting connection with Ammanford, just seven miles north along the Loughour from Hendy.

In 1891 he spent a year as a pupil at the Gwynfryn School, Ammanford, a preparatory school that catered mainly for nonconformist ministerial candidates studying to become chapel preachers. He returned to Gwynfryn as assistant to the headmaster, Watcyn Wyn, in 1897. There he taught Latin, Greek, Mathematics and English for the next eight years until 1905, when he entered Jesus College, Oxford. He graduated in the Theological School in 1908. He then returned to Gwynfryn where he became headmaster (Watcyn Wyn had died in 1905) until the closure of Gwynfryn in 1915. A shortage of students caused by the outbreak of World War I in 1914 was compounded by the opening of Amman Valley County School the same year just four hundred yards from Gwynfryn (the school was renamed Amman Valley Grammar School in 1945). Gwili married Mary E Lewis from Ammanford in 1910 and after the closure of Gwynfryn they moved from their Ammanford home to Cardiff in 1918 where Gwili took up a lectureship at Cardiff University.

Gwli will forever be associated with the major English poet Edward Thomas (1878-1917) with whom he had a close, twenty year long friendship after they first met in 1897 until Thomas's death at the Battle of Arras in 1917 (see The Poet Edward Thomas and Ammanford in the People section of this website). But Gwili's story is worth telling in its own right and the following biography is taken from Llanelli Lives, by Howard M. Jones, published by Gwasg y Draenog, Pontardulais, 2001, pages 201-208.

For children of the working class in Gwili's era there was no education available beyond a rudimentary schooling until 12 years of age, after which work in the coal mines, factories or on the land beckoned with a grim inevitability. The non-conformist churches were able to augment this scant schooling through the Sunday School movement where children could attain very high standards of literacy and numeracy, taught entirely by members of their chapels. An idea of what could be done with this limited education comes from the life of an Ammanford child David W. Davies (1854-1937), the son of a farm labourer. When this boy left Ammanford with his family in 1860 they left a life of abject poverty behind them; when the same boy died in 1837, aged 83 years old, he left a fortune in his will worth £24 million at today's values from his subsequent life as a coal and tinplate magnate in the nearby Swansea valley:

D. W. Davies had no formal education, but improved his knowledge in chapel, Sunday School, penny readings and eisteddfodau. He learnt Psalms and chapters from the Bible and sometimes recited them in Pantteg Chapel, where he was a senior deacon. He was proud to relate that he won a first prize at an eisteddfod at Tabernacle, Morriston, on the subject “Gwell bys na dwrn i agor drws.” (Better finger than fist to open a door.) His culture was based on the Bible. (A History of Pontardawe and District, John Henry Davies, pages 83-84, published in 1967.)

This was the same culture Gwili was born into and he made the very best use of what education was available. If a child was talented and diligent enough, and if parents were prepared to make financial sacrifices, then paying to continue further in education offered a glimmer of hope in an otherwise dark world. Although his own father was an illiterate tinplate worker, Gwili was one of the very few working-class children from those years who was able to turn that hope into reality. Gwili may not have had the material success of a David Davies but within the academic world he chose instead he rose to the top of his profession. Studying for the Christian ministry, usually in one of the non-conformist denominations, was a common escape route for such children, and the one that Gwili initially chose, though his eventual future would lie in education. Preaching and teaching is a convenient rhyming description for the Welsh of the 19th century, as it would be well into the twentieth century also.

GWILI

From Llanelli Lives, by Howard M Jones,

Gwasg y Draenog,

Pontardulais, 2001, pages 201-208The poet John Jenkins (Gwili, 1872-1936) was born at Hendy, Carmarthenshire, the fifth child of a “metal refiner”. In a poem Gwili described his father as:

Na dim ond harn di-fai bob darn

Oedd gan fy nhad i'w wado mas.[My father beat out only/Flawless sections of iron.]

His father, born in 1829, came from Aberdare but moved to Cwmafon as a little boy and then to Dafen (see note 1 below) around 1849 in search of employment in the new works there. In 1869, with his four children, there was another move to Pontarddulais at the time when the Hendy Tinplate Works commenced. The family went to live with grandmother Jenkins in Iscoed Road, Hendy, when she became a widow; and Gwili was born in the house which is now opposite Hendy RFC. After the death of his grandmother in 1876, Gwili found himself at Gwili Cottage at the bottom of what is now River Terrace. The house, situated next to the Gwili River, probably led to his love of fishing, as well as giving him his Bardic title.

His father had a good memory and sang many old ballads when he felt so inclined although he was unable to read and write. Gwili's mother had a great influence on him as she was actively religious with a wide knowledge of the Bible. She was involved in starting the Baptist movement at Dafen (Maescanner) when she resided there; and later on helped initiate Tabernacl Chapel at Pontarddulais. Gwili and his mother were two of the first members at Calfaria Baptist Chapel in Hendy — his father being a member of Yr Hen Gapel (Tynewydd] at Hendy.

An outstanding pupil at Hendy Primary School, Gwili became a student teacher there between 1887 and 1890. His headmaster was David Jones BA, Y Mishtir Bach, [the little schoolmaster] who later became Rector to King Edward VII at Sandringham — he died there in 1906 — and who exerted a strong influence on the boy. His literary education was influenced by his friendship with the Llangennech poet Morleisfab.

At the age of 14, Gwili, then merely called John Jenkins, had a poem published in the Llanelly “Guardian” (his first? See note 2 below). There are four verses and it shows the poet's social awareness even at this tender age.

Croesaw i ti flwyddyn newydd

Meddai torf o weithwyr cu

Fu'n cardota trwy'r “hen flwyddyn”

Yn em gwlad o dy i dy.[Greetings New Year cold/The docile workmen say/We've begged throughout the old/From door to door all day.]

In 1891 Gwili attended the Athenaeum School in Llanelli but stayed for only one term as the school was disbanding. In August of the same year he attended Gwynfryn School (see note 3 below) in Ammanford as a pupil with the intention of studying Greek and Latin. He stayed for one year. At this time, Gwili began to preach and, in 1892, he left for Bangor to attend the Baptists' College there.

His time at the Baptist College was a fast and furious one. Apart from the preparations for his Sunday sermons at different chapels, there was the writing of lengthy poems for numerous eisteddfodau. Gwili also read voraciously from books which were frequently not on the exam syllabus. He even found time to appear as goalkeeper for the College soccer team against the “town” lads in 1894. An idea of his industry can be seen from his diary entries for 1893:

7th September, 1893.

“Won the essay competition at Abergwili Eisteddfod.”22nd September, 1893.

“Have written 530 lines of my poem on Tennyson.”7th October, 1893.

“Wrote an adjudication on an ode for ‘Baner ac Amserau Cymru'.”18th October, 1893.

“Have written 48 lines for my poem for Caernarfon Eisteddfod.”Competing at eisteddfodau had started in earnest in 1892 when he was second for the Chair competition at Bettws near Ammanford. His first Chair was won at the Lampeter Eisteddfod which around 6,000 people attended in 1894. Also in 1894 he was joint second for the Crown at the National Eisteddfod in Caernarfon and won a gold medal at Pwllheli Eisteddfod.

This pattern of success was repeated in different places in 1895 although he was economical with his effort in winning a Chair at Cefnmawr — as he had already submitted the same poem when he came second at Dolgellau a few months earlier.

The artistic effort involved in all his work; his winning poem at Llanelli Oddfellows Eisteddfod was 408 lines long, resulted in Gwili failing to pass the external Intermediate examination of the University of London in July 1896. He, therefore, left the College without a degree and not having been offered a permanent place as minister of a chapel. There seems to have been a few reasons why this was so, although his biographer, E. Cefni Jones (see note 4 below) suggests that Gwili was in fact offered places, but turned them down. His contemporaries found that he spoke too quickly in the pulpit and, in later life, the growth of a moustache made his delivery indistinct. His Hendy dialect would also have made him reasonably incomprehensible to his Northern congregations. However, his biographer asserts that the effort required to write two sermons would have been too great for Gwili whose single sermons went to extreme lengths.

In June of 1896 Gwili returned home to Hendy and stayed there before starting another course in University College, Cardiff, in October. In December he started writing for “Seren Cymru” articles called “Literary Letters” but this was a very low period in his life when his prospects seemed quite grim. In March of 1897 he returned from Cardiff after giving up his University course and he did not return there as a student.

Gwili continued to compete in eisteddfodau and won the Chairs at Corwen on 2nd August and Cwrt Henri on 4th October, 1897. In September of that year the English poet Edward Thomas, who had relatives in the area, came to visit him in Hendy and this started a friendship which lasted until Thomas's death in 1917.

In this period, Gwili's financial situation must have been precarious as he relied on “supply” sermonising and income from adjudicating and journalism. On 11th October, 1897, however, he started work as assistant teacher in Watcyn Wyn's school at Ammanford where he had been a student in 1891. He taught Latin, Greek, Mathematics, and English and stayed at the school for eight years. He continued to live at Hendy, rising at five in the morning to catch the train to Ammanford. He was popular with the students as he could empathise with their situations, although one of his endearing traits was his absent mindedness — he had to buy a neck scarf on average once a month!

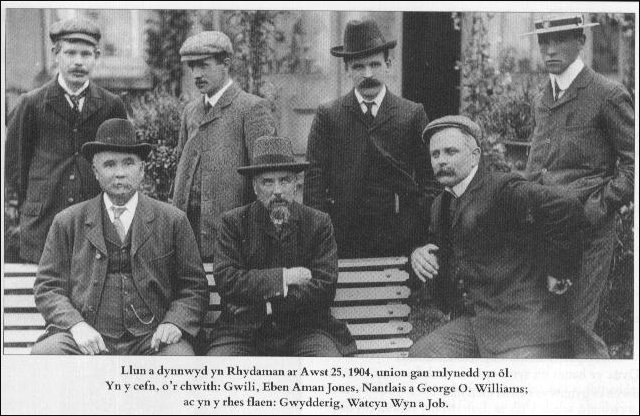

Photo: A gathering of poets and preachers in Ammanford in 1904. Close friend of Edward Thomas, John Jenkins (Gwili), is first left, top row. Poet Watcyn Wyn (in the centre of the bottom row) was headmaster of Gwynfryn School, Ammanford (a biography of Watcyn Wyn can be found in the 'People' section of the website, or click HERE). Methodist preacher, poet and hymnist Nantlais is top row, third from left (a biography of Nantlais can be found in the 'People' section of the website, or click HERE). The text below the photo reads: "Picture taken in Ammanford on August 25th 1904, a hundred years ago. In the back, from left: Gwili, Eben Aman Jones, Nantlais and George O. Williams; and in the front row: Gwydderig, Watcyn Wyn and Job." (Photo from Summer 2004 edition of 'Barddas'). Gwili had further eisteddfodic successes at Corwen (Chair) in 1899; and Dolgellau (Chair) in 1901; before his ultimate triumph in winning the Crown at the National Eisteddfod in Merthyr in 1901, at the seventh attempt.

The “Llanelly Mercury” of 12th September, 1901, reported that there was the usual re-crowning ceremony of the winning poet at Hope Chapel, Pontarddulais, following Gwili's success at Merthyr. One of the poems published on 26th September to celebrate the occasion highlights the competitive edge that existed between the inhabitants of the villages of Hendy and Pontarddulais.

Mae Sir Forgannwg am y clod

Ond i Sir Gaer y daeth y god;

I'r Hendy, nid i'r Bont, wrth gwrs

Y daeth y goron, ‘r aur a'r pwrs.

..........Rhydderch y Bryn (R.J. Jones of Pontarddulais)[Glamorgan wants the glory/Carmarthen got the trophy/To Hendy not to Bont of course/Came Crown and gold and purse.]

Mae'r afon oedd yn fechan

Ie nemawr fwy na nant —

‘Nawr wedi codi ysgwydd

Yn uwch na thir y pant;

Na sonier am yr Amason

Ar Mississippi mwy

Mae afon yn yr Hendy

Yn fwy ei bri na'r ddwy.

..........Rhandir (William Morgan,1864-1937)[The river that was little/Scarce bigger than a brook/Has risen now its shoulder/‘Tis higher than the bank/Don't mention Mississippi/Or Amazon combined/There's a river in Hendy/That leaves them both behind.]

It was left to the poet T. E. Nicholas (Niclas y Glais) to add a touch of irony, typical of his later work:

O'r diwedd disgynnodd y Goron

Ar ben bedyddiedig wr

Daeth Enwad i'r golwg yn Gwili

Ar ôl bod yn hir dan y dwr.[On to a Baptised gentleman/The crown did then alight/With Gwili a denomination/Emerged from the depths to sight.]

Gwili did not compete in as many eisteddfodau after his success in 1901, although he won an essay prize in 1904 as well as another Chair at Eisteddfod Meirion in 1907. He was an adjudicator at the Llanelli National Eisteddfod of 1903 in the Chair competition.

There is a continual striving for academic success in Gwili's life and, in 1905, he decided to enter yet another course of study in Oxford. In February of 1905 he preached at Castle Street, London when Lloyd George was in the congregation; and afterwards visited the Oxford Colleges when he called upon O. M. Edwards. On 29th June of that year there was a farewell gathering of his friends at Gwynfryn before the poet went to recommence his studies. Watcyn Wyn wrote a suitable englyn for the occasion:

Ein Gwili sy'n mynd or golwg — ond mynd

..........y mae i le amlwg;

Ac oni dry'n fachgen drwg,

Gwili ddaw eto ir golwg.[Our Gwili now is going/To a far far better place/Unless he turns a naughty boy/We'll see again his face.]

Gwili entered Oxford as a student at the ripe old age of 33 on 12th October, 1905. Initially he studied “Greats”, i.e. Latin, Greek, Ancient Philosophy and History, and did in fact pass the first year examinations in these subjects. However, he obtained a second class honours degree in Theology in 1908 from Jesus College, having changed his course in mid-stream. According to the University regulations of the time, he would have been awarded an MA degree automatically after a period of seven years, viz, in 1915.

Gwili's mother left Hendy in 1906 in order to live with her daughters in Cardiff. This meant that the poet's connection with the village was severed at this time, although he often returned in later years.

His competitive instinct had not totally disappeared as he won seven guineas at the Mid-Rhondda (Tonypandy) Eisteddfod for his collection of lyrics in 1908. At the National Eisteddfod of 1907 he provided the lyrics for D. Vaughan Thomas's musical work “Llyn Y Fan”.

This industrious peripatetic preacher cum poet-scholar was still unsure of himself. His biographer states that his diary entries for 1908 contain such phrases as “What will become of me?” and “What will I do?” What he did was to return to the Gwynfryn School in 1909 for the third time — in order to take over the establishment. His industry must have been amazing as he entered and passed yet another academic hurdle — the external Intermediate examination of the University of London in July of 1909.

The period preceding the First World War brought happiness in the form of his marriage to “Miss M. E. Lewis of Ammanford”. This is reflected in the quality of his lyrics written for the National Eisteddfod at Carmarthen in 1911 which won him the princely sum of £5. His first daughter, Nest, was born in 1912 followed by Gwen in 1914.

It's not easy to see the effect that the First World War had on the poet. Although Gwynfryn School had to close on account of the hostilities, other opportunities occurred which may not have been available in peace-time. Gwili became editor of “Seren Cymru”, the Baptist Journal, in 1914 and retained this position until 1927. At this time he also started writing the Welsh section of the newspaper the “Amman Valley Chronicle”.

As an adjudicator, Gwili had some sympathy with the new wave in Welsh poetry exemplified by the work of T. H. Parry-Williams. In the National Eisteddfod at Bangor in 1915, his adjudication of Parry-Williams' “Y Ddinas” [The City] stated that it was:

“yn gyfoethog ei hiaith ac yn gref ci hawenyddiaeth.”

[rich in its language and mighty in its inspiration.]

During the First World War he often adopted a courageous position regarding conscription, but it has been stated that his ideas were not consistent however eloquently they were expressed. In the 19th November, 1915, edition of “Seren Cymru” he said that:

“Nid gwaith gweinidog o eglwys rhydd yw cymell neb i ymrestru. Ni ddylai ddwyn arf ei hun, ac ni ddylai annog arall i ddwyn arf.”

[It is not the task of an independent chapel minister to compel anyone to sign on. He should not bear arms himself nor urge anyone else to do likewise.]

Perhaps, to quote Beverley Smith (see note 5 below), Gwili gave to “Seren Cymru” an importance that no other denominational publication attained in later times. He urged Chapel Ministers to become more involved in current affairs and, at the very least, to read the literature of the Fabian Society and the Independent Labour Party. He also urged colleges to run courses in economics for their students. His disappointment in the politics of Lloyd George led to the publication of thirteen anti-Liberal articles in “Seren Cymru” between 1915 and 1921. This caused Lloyd George some distress as “Seren Cymru” was read regularly by the Non-conformist politician.

Another of Gwili's courageous stances came with his sympathetic treatment of the events in Ireland at Easter, 1916. He wrote an article on “Sinn Fein” in “Seren Cymru” on 5th May that year, stating that:

“Rhyfel yw'r rhyfel hwn, fe'n sicrheir, dros fuddiannau'r cenhedloedd bychain. Yr ydym yn hennaf, meddir, yn yrnladd dros hawliau Belgium, Serbia, Montenegro, a Pholand i fyw eu bywyd eu hunain, heb fod achos iddynt ofni'r dwrn haearn mwy. Os felly, gweddus fydd i Senedd Prydain ganiatau, fel ceid gyfreithlon, hawl yr Iwerddon i'w chais am fyw ci hywyd arhennig ei hun, ac i Gymru ac Ysgotland yr unrhyw hawlfraint. Ystyr “Sinn Fein” yw “ni'n hunain”.

[We are assured that this war [WW1] is a war over the rights of small nations. It is said that we are fighting mainly for the rights of Belgium, Serbia, Montenegro, and Poland to live their own lives without having cause to fear anymore the iron fist. If this is so, it should be proper that the British Parliament grants, as is lawful, the rights of Ireland, its request for living its own particular life, and to give Wales and Scotland the same rights. The meaning of “Sinn Fein” is “we on our own”.]

A post came available in the Celtic Department of Cardiff University in 1917 and although Gwili had graduated in Theology his wide knowledge of Celtic studies qualified him for the job. The family moved from Ammanford to Cardiff in 1918. He found time to write a thesis on “The Study of the Gospels in Mediaeval Welsh” for which he obtained a B.Litt. from Oxford University in 1918. During 1918 he was “acting” head of the Celtic (later Welsh) Department for some months, but on the return of W. J. Gruffydd (who had been on active service in the Navy) his contract came to an end and he became Librarian at the Salisbury Library. At this time Gwili's collected English poems were published by the “Western Mail”, however, his contract at the Library lasted only until 1921 when he had to seek a suitable post for a man of his abilities.

One of the reasons that he had gone to the Baptist College as a student in 1892 was the presence on the staff of Professor (later Principal) Silas Morris MA (1861-1923) who was a native of Pontarddulais and a friend of the family. His father and Silas Morris's father had been employees of Hendy Works and their mothers were members of the same chapel at one period. The professor had taken an interest in Gwili's well-being as a student and again proved to be an influence in his life. His death in 1923 led to Gwili's appointment as Professor of New Testament Greek in the Baptist College and a lecturer at Bangor Theological College. This meant that Gwili gave lectures at the University as well as at the Baptist College.

To the end of his life his material circumstance were easier. Like many of the celebrated literati, he acquired two “summer houses” in Pembrokeshire. He even purchased a motor car which he relied on other members of his family to drive.

In June 1929 his magnum opus appeared, viz. “Arweiniad i'r Testament Newydd” [Guide to the New Testament] which went to 650 pages and earned him a £50 prize at the Liverpool Welsh National Eisteddfod of that year. He became editor of “Seren Gomer” in 1929 and was elected Archdruid in the Bangor Eisteddfod of 1931. During 1932 he started a series of sermons which were broadcast on BBC Wales and also received an honorary D.Litt. from Oxford University. There was a return to try and boost the fortunes of “Seren Cymru” as editor, and he started weekly articles in the “News Chronicle”.

During 1936 his health began to fail and his diary entries stop in April of that year. He died on 16th May and the children of Hendy were given a half-day holiday to line the streets before his funeral at Hen Gapel. There were over seven hundred letters and telegrams of condolence sent to the family (see note 6 below).

FOOTNOTES

1. Dafen Tinplate works commenced in 1846.

2. “Llanelly and County Guardian”, 13th January, 1887.

3. This college was opened in 1880 by Watcyn Wyn to prepare young ministers for entry to different colleges.

4. E. Cefni Jones; Gwili — Cofiant a Phregethau.

5. J. Beverley Smith; Transactions of the Cymmrodorion Society, 1974; page 203.

6. “Llanelly Mercury”, 28th May, 1936.

(From: Llanelli Lives, Howard M Jones, Gwasg y Draenog (Hedgehog Press), Pontardulais, 2001, pages 201-208.)