| Civil

Liberties IN

THEIR frenzy to smash the miners' strike the government judiciary and the police

took gigantic steps to reduce the civil liberties of the striking miners and their

supporters. Perhaps

the first outrage was the public declaration of the Attorney General Sir Michael

Havers on a radio programme that the police had sufficient power to stop pickets

travelling to pits if they took the view that a breach of the peace might take

place. Within hours of this declaration the Kent police put a road block across

the Dartford Tunnel some one hundred miles away from the closest Midlands pits

and stopped any car that looked as if it might be carrying Kent miners, and threatening

the men with arrest if they went through the tunnel. After injunction proceedings

brought by the Kent NUM, and a considerable protest by the public, the Attorney

General remained silent, but the pattern had been set.

From then on massive

forces of police blocked various routes from the M1 leading to the Midlands pits

and prevented the miners and their supporters from getting anywhere near the pits

they wished to picket peacefully. Any foreign visitor driving along the Ml could

have been forgiven for thinking that they were entering a high security war zone

judging by the enormous numbers of police and police vehicles which either blocked

the roads, stood parked along the verges or travelled systematically in long convoys

from one area to another. No

longer could a miner exercise his lawful right to travel peacefully to any other

part of the country without being stopped. No longer could any other man or group

of men who looked like miners travel peacefully through the Midlands without being

stopped by the police. The

government openly exhorted the police to take whatever steps the police thought

necessary to stop picketing and enable the few pits that were still producing

coal to continue working. They lavished money on the police despite generally

denying there was no money for public expenditure in even the most needy areas

of the deprived inner cities. Was there an outcry from the government when one

southern constabulary chartered a jet to carry the police from the southern counties

to the Midlands for picket duties? The

government carried out an active campaign throughout the media wholly blaming

the striking miners for violence on the picket line, as well as totally ignoring

the escalating violence in the police and the continuing erosion of the public's

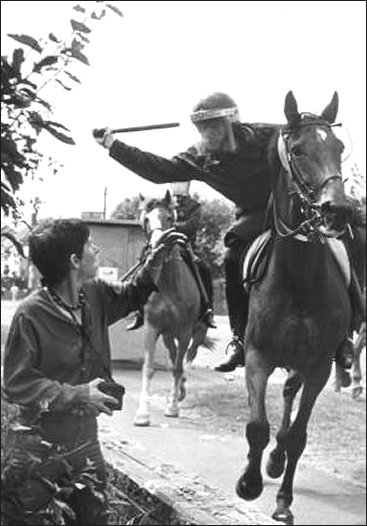

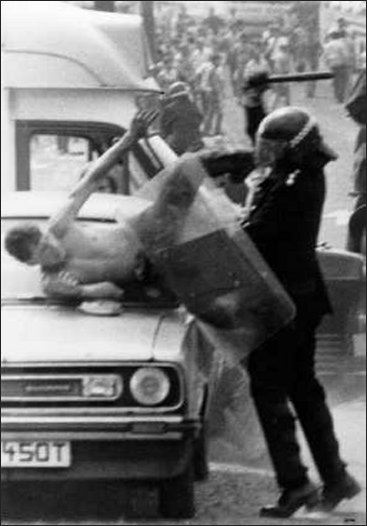

rights. Police were encouraged and allowed to use pre-emptive charges by batten

swinging police horsemen. They were allowed and encouraged to use snatch squads

often of heavily armoured policemen who would force their way into a line of pickets

to break up the line and give other constables opportunities to arrest pickets

without reason. Evidence at the Orgreave trial revealed internal police directions

which actively encouraged the police officers to use violence when dealing with

picketing. The

government assisted in the organisation and paid for the National Reporting Centre,

the first attempt in Britain to organise policing on a national strategic level

without taking into account any of the needs or views of local inhabitants. The

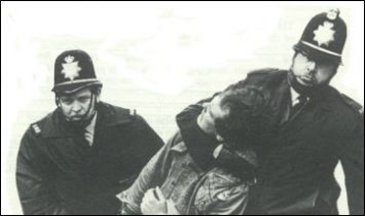

police for their part generally pursued a vigorous aggressive campaign against

striking miners. The policemen on picket duties in many areas were encouraged

to view striking miners as the enemy. The frequently used excessive violence on

even elderly miners who were arrested for trivial offences and despite the fact

that no resistance was offered by the men. The miners were abused and openly insulted

by the police who faced them on the picket lines. There was no prosecution of

police officers who were seen to assault pickets, even when clear evidence of

the attacks were shown on the television. The

police openly refused to allow pickets to speak peacefully to miners who were

going to work. The pickets who managed to get through the road blocks were kept

even a half a mile or more away from the pit gate. Gone completely are the days

when it was accepted law that a number of pickets could stand across the workplace

gate and speak to their fellow workers going into work so as to try to put the

striker's point of view. The police developed the tactic of making mass arrests

in order to completely remove pickets from the picket line, knowing that the magistrates

would impose bail conditions that were so oppressive that the result would be

that the men could no longer take part in the strike. In

Colchester the police went even further and arrested pickets who were behaving

quite peacefully so as to reduce the number of potential pickets in one area to

prevent the possibility of a breach of the peace. The Colchester police had no

intention of charging any of these men, and indeed there was no suggestion that

any crime had been committed. Nevertheless, the dozen pickets found they were

unlawfully imprisoned in a Colchester police garage for a day. Not

satisfied with the Public Order Act offences the police resorted to the ancient

crime of watching and besetting under the Conspiracy and Protection of Property

Act 1875. Several men, including a passing farmer, were arrested in their pit

village in Kent for standing on a street corner talking. All the men were found

not guilty by the magistrates, there being no evidence against the defendants.

The police rapidly dropped the case against the farmer when they realised their

blunder. The Act

was also used against 21 kent miners who were following in their motor cars behind

a convoy of four police cars, and an NCB bus. The police alleged that the occupants

of the bus were intimidated by the men in the vehicles up to half a mile behind,

and out of vision. A novel if not vicious approach by the police. All the men

were acquitted. Perhaps

the most serious prosecutions, however, were those in the Midlands and Yorkshire

where dozens of miners are accused of unlawful assembly and riot. The evidence

when presented by the prosecution was non-existent and exposed an overwhelming

prejudice of senior policemen towards the miners on strike. The country now knows

from the details of the remaining cases which were dropped by the prosecution

that there was no substance in the charges brought against the men who were doing

no more than standing up for the jobs of themselves, their workmates and their

children. It has

always been a working rule that prosecutions should not be brought unless there

is a reasonable prospect of the offence being proved. Indeed the DPP will not

prosecute a policeman accused of a crime unless there is more than a 51% chance

of the prosecution succeeding. The police during the strike, particularly in relation

to the most serious charges, worked on the basis that they should charge the miners

on the basis of prejudice, assertions made by Ministers of the government, and

senior employees of the NCB and allegations carried by the media. Pickets

have been brought before the magistrates on and off over the years, but the dispute

soon saw magistrates setting bail conditions in respect of largely trivial crimes

which were so oppressive that even the most conservative of lawyers found them

unjustifiable. Indeed, in the early days of the strike the Essex magistrates ordered

bail restrictions that prevented Kent miners from picketing at any of the three

ports in Essex where coal was being imported, even though the alleged offence

occurred at only one of the ports. This was despite the fact that some of the

alleged offences were no more than sitting down in the road. The magistrates'

aim was clearly to drive the miners out of Essex. The

magistrates in Ramsgate who first of all restricted Kent miners from picketing

anywhere in Kent, including their own pits went even further in other cases by

restricting the men from picketing anywhere at all. These magistrates took it

upon themselves to prevent the men from fighting for their jobs. The conditions

were so hastily imposed that men found that they were in breach of the conditions

by going to the local Tesco's to shop, to their doctors or the hospital and in

some instances even to their own homes. One London magistrate upon hearing that

the accused miner was not a resident in London imposed a condition of bail that

he should not come to London for any reason whatsoever. No

matter what arguments were put up by lawyers representing the miners they were

not listened to because the magistrates were showing their class colours. In Mansfield

the magistrates even had bail notices with bail restrictions pre-printed ready

to hand out to the accused miners even before their names were read out in court. What

did the High Court Judges do to prevent this appalling erosion of civil liberties?

They stood by and either condoned the erosion without any care whatsoever or formally

supported the erosion of liberties in order to suppress the miners' strike. An

application for an injunction against the Kent police for blocking the Dartford

Tunnel failed. The judge was not sufficiently interested to safeguard the individual's

rights to travel peacefully across the country. The applications to the Divisional

Court for an order preventing the police road blocks in the Midlands failed, the

court endorsing the police action. The

application to the High Court to quash Mansfield's preprinted bail notices was

lost, the judges endorsing the magistrates' actions. Already

the general erosion of civil liberties which occurred during the miners' strike

is being felt by the public. There are calls for longer prison sentences by those

in power. Magistrates now feel much more ready to impose stringent bail conditions.

The police have developed an aggressive mode of dealing with other strikers and

dissenters. The Police and Criminal Evidence Act was passed by Parliament giving

the police much wider powers to deal with the public. Plastic bullets and tear

gas will be used in inner city disturbances and it will not be long before a coach

load of CND supporters are prevented from travelling to a demonstration. Those

who have fought for civil liberties over the past fifty years are aware of the

adage – "give the police an inch and they will take a mile". Date

this page updated: September 29, 2006

|