|

|

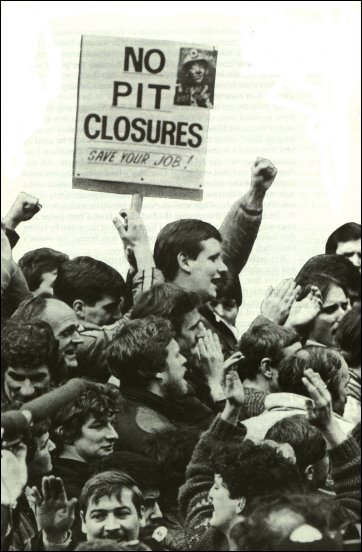

Lobby after NUM executive meeting in Sheffield 8th March 1984.

Photo: John Sturrock/Network

|

|

|

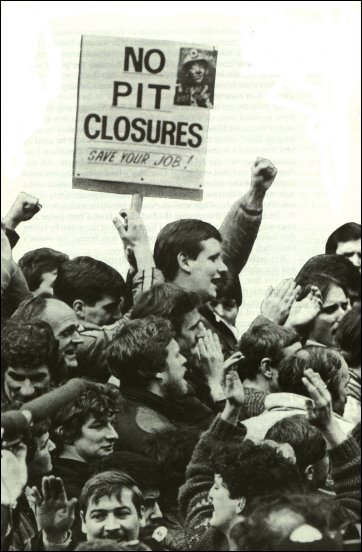

Lobby after NUM executive meeting in Sheffield 8th March 1984.

Photo: John Sturrock/Network

|

|

| ||

| History of the Strike WHEN DOES the history of the miners' strike really start? There are many factors which contributed to the complex situation preceding the strike. Does it start with the Ridley Plan in 1977 -- the plan in which Nicholas Ridley set out the guidelines for a future conservative government to take on the trade unions, the weakest first, the strongest last? Much of the detail of the strategy we saw in the miners' strike – the build-up of coal stocks, the use of the police, the use of lorries to transport coal – was prefigured in the Ridley Plan. Or does the history of the strike really start with the election of the Tories in 1979? Or with the infamous cabinet minute shortly afterwards, which spoke of the ability to massively increase reliance on nuclear power in order to minimise the industrial and political strength of the National Union of Mineworkers? Was the strike the inevitable Tory revenge for their defeats at the hands of the miners in 1972 and 1974? Could the strike really be traced back to the election of Arthur Scargill as President of the NUM – an almost unique trade union leader whose commitment to fight for the policies of the NUM Conference was utterly unswerving? Many people would say that the setbacks suffered by other major trade unions – the steel workers, ASLEF over flexible rostering, the Health Service workers, and the NGA in the Warrington Messenger dispute – gave the clear indication that neither the TUC leadership nor the Parliamentary Opposition had recognised the outright confrontation being provoked by the government nor had the guts to stand up to it. Moreover, the experience of the trial runs in those disputes showed that the use of the police and the courts against working people would be grudgingly tolerated by some of the Labour movement's leadership. It could be argued that it was then inevitable that Mrs Thatcher would see the NUM as a prize to be coveted and the stronghold of the miners as a bastion to be stormed. Or could one identify the appointment of Ian MacGregor as the moment at which the strike became inevitable? Given his record at British Leyland (appointed by a Labour government) and later at the British Steel Corporation, it was quite clear that he was appointed by the Prime Minister as Chairman of the National Coal Board with a mandate to butcher the mining industry. In an immediate sense, the strike was provoked with MacGregor's announcement that another 4 million tonnes of capacity – leading to a loss of 20,000 jobs – was to be taken out of the industry, and then announcements of the closure of Cortonwood Colliery and the four other pits under immediate threat at that time, without reference to established procedure for closures. No-one should have been surprised at this development. Arthur Scargill had repeatedly warned of the government's intentions and of the NCB hit lists, and he was right. Indeed, it is instructive to note how many times what appeared to be key Government and NCB arguments against the NUM subsequently turned out to be issues on which the NUM was proved correct. One only has to trace the propaganda offensive that accompanied the NACODS agreement', with Mrs Thatcher and Peter Walker continually urging the NUM to settle on a similar basis. But the NACODS leadership rapidly recognized that their agreement was worthless. And in the spate of pit closures which followed the end of the strike, none was subjected to the new independent review procedure which had been hailed as a great breakthrough by the Government in the NACODS agreement. Or as another example of the way in which propaganda was used in a blatant attempt to shape the popular view of the dispute, one can trace the television and newspaper hysteria surrounding the long struggle to successfully picket Orgreave. There was daily coverage of hysterical statements from Thatcher, Walker and any number of Tory backbench MPs castigating the pickets, as the organised police thuggery, based on their new Manual of Procedures, went on day after day – unmentioned by the media. But we now know a later chapter in that history has been the acquittal of almost every miner arrested, with many not even facing trial because the police were forced to withdrew charges. We now know that the television news bulletins were blatantly doctored to give the opposite impression to what in fact took place. An even longer historical memory will find it staggering that the Tory inspired issue of a ballot could be turned into such a serious matter by the NCB and the government – and unfortunately by some leading members of the Labour Party and that it could be used by Mrs Thatcher's friendly Tory judges as a basis for Common Law decisions against the NUM at National and Area levels. All this despite the fact that under Joe Gormley's leadership, the National Executive of the union defied a National Conference decision and a national ballot that went overwhelmingly against productivity deals, and allowed the Nottinghamshire Area to negotiate such a deal with the NCB. And all this despite the fact that a High Court judge had responded to the South Wales and Kent Areas of the union by ruling that ballots and conference decisions in no way bound the union's executive. Any serious study of the strike will have to conclude that the strike was not about ballots, not about violence, not about trade unions and the law, but about jobs and communities. In a sense, it was remarkable that so many could struggle for so long and for no gain to themselves. It was not a selfish strike, but one based on the finest principles of the strong defending the weak. And as time passes, it becomes increasingly more obvious that the miners were right to make their stand; week by week, it becomes increasingly more apparent that it is the clear intention of the NCB and the government to achieve the destruction of the mining industry, the miners' union and in turn to deal a mortal blow to organised resistance by working people to their policies of the New Right. And no historical view could fail to observe the unique situation of a major national trade union being put into Receivership, deprived of all its funds, and operating for over a year on the basis of goodwill and donations from sympathisers and supporters in the Labour Movement. The ability of a Conservative government to get away with such a threatened elimination of its opponents will he something which for many years to come will lead people to ask why the wider trade union and Labour movement could have allowed such things to happen without retaliation. Before the miners' strike, there was a view that was becoming increasingly fashionable, particularly among those who talk of a re-alignment of the Left, that class struggle was a thing of the past. We even heard it said that the present generation of industrial workers, including miners, many with mortgages, hire purchase commitments, foreign holidays and cars, would never again endure a strike of such length and proportions. The miners' strike showed that such a view was nonsense. Not only did the miners themselves, particularly the younger miners, show an almost historically unparalleled determination to win, but another remarkable phenomenon of the strike was the equal determination of the women of the mining communities to participate shoulder to shoulder with their menfolk. If the leadership of the Labour Party, the TUC, and the leading unions, had looked after their own class – the working class – in the way that Thatcher and the Tories looked after their class, the outcome of that strike – and British society – would have been quiite, quite different. Had they chosen instead a commitment to those in active struggle, then future historians might have recorded that the 1984-85 miners' strike was the beginning of the end of the Thatcher government and all that it stood for. Instead, it marked the beginning of the end for British manufacuring. The miners showed that resistance is possible, and the determined manner in which that resistance was crushed by a Tory Party showed clearly how it was intent on maintaining the last vestiges of a capitalist society. Other working people joined that resistance, hoping for the transformation of society to one based on the commonwealth of working people and their families. It was not to be, and Thatcherism and its evil offspring, New Labour, have wreaked havoc on working communities ever since. | |||

|

Date this page updated: September 29, 2006 | |||

Emergency services rescue a miner buried alive whilst riddling for coal amongst the pit waste for fuel during the year long Miners strike. Silverwood colliery 1985 Date: 18/02/85.

Copyright John Harris. E-mail: j.harries@reportsdigital.co.uk. NUJ recommended terms and conditions apply. Moral rights reserved under Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1965. Credit is required. No part of this photo is to be stored, reproduced or transmitted by any means without permission. Website: http://www.reportdigital.co.uk